print, photography, engraving

# print

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

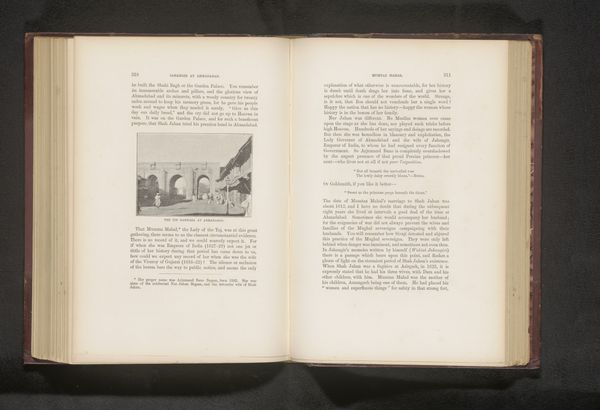

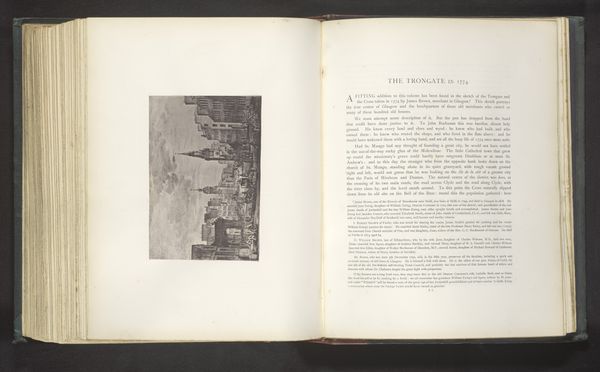

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 81 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today, we're looking at "Church gate, Bombay, 1863," an engraving from an anonymous artist housed at the Rijksmuseum. It captures a cityscape during British colonial rule. What’s your initial take? Editor: My first thought is one of quiet observation. The stark lines create an almost austere scene. It feels meticulously rendered yet emotionally detached, the stone and metal components precisely delineate the architectural form. Curator: It's an intriguing choice by the artist to capture this gate through the lens of Orientalism. Notice the strategic placement of the gate itself. This imagery really underscored the imposing presence of colonial structures and power. What do you think about its intended audience? Editor: It was almost certainly geared towards a Western audience. I think it aimed to romanticize and exoticize Bombay through visual imagery that perpetuated this sense of colonial dominance and 'otherness.' What stories are not being told, considering the absence of human presence at such a bustling urban node? Curator: That's right; absence speaks volumes. The locals are present by omission. What’s key is understanding the relationship between these artistic productions, the global trade routes, and the local labor required to erect such colonial outposts. Consider the consumption and distribution chains tied to these prints— who made it possible for these images to reach Western homes and influence public opinion? Editor: Absolutely, framing the engraving within larger geopolitical currents allows us to expose power relations inherent in its creation and reception. It prompts vital dialogue regarding whose stories get told and by whom. Considering our current reckoning with the colonial past, how might contemporary artists reclaim such visuals? Curator: Perhaps, they might juxtapose these historical scenes with accounts by local communities impacted by colonial policies, or reveal the hidden figures whose labor supported such monumental projects. They could disrupt our comfortable viewing by asking pertinent questions regarding privilege and agency, while simultaneously unveiling untold narratives suppressed by hegemonic narratives. Editor: Looking closely reveals its lasting legacy— and how even seemingly innocuous imagery solidifies skewed power relations that remain profoundly present today. Curator: Precisely; now we can better appreciate both the artwork and the sociopolitical conditions in which it emerged.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.