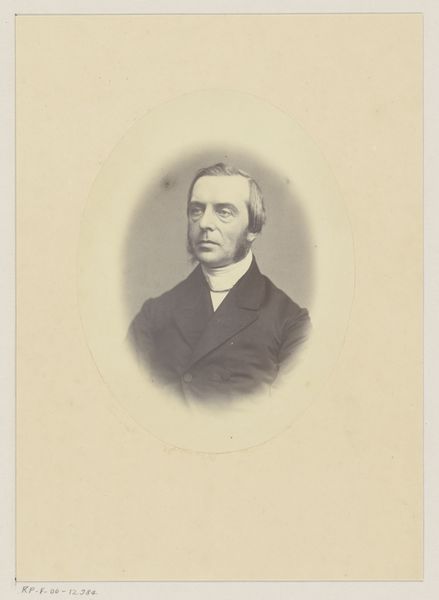

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

romanticism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

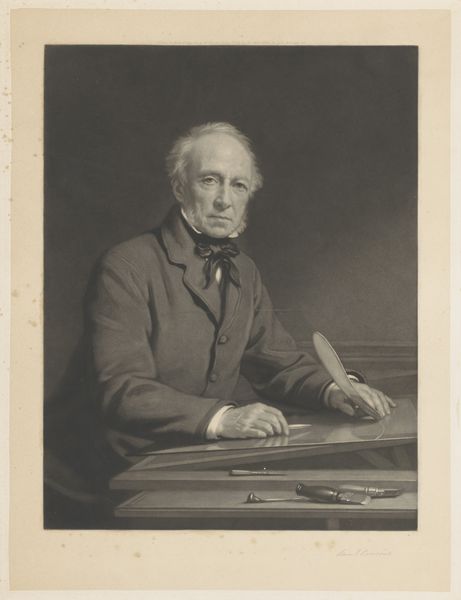

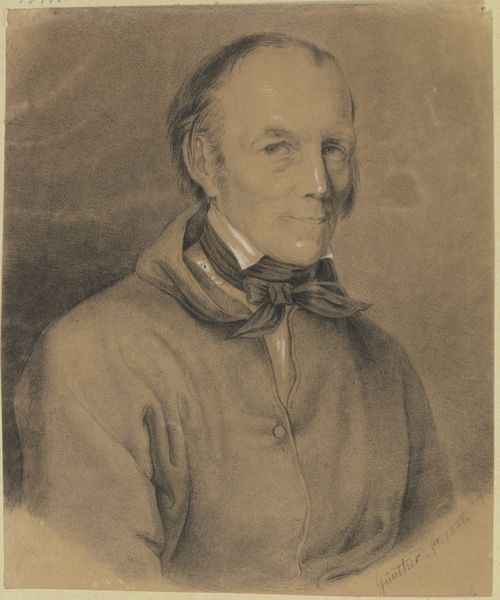

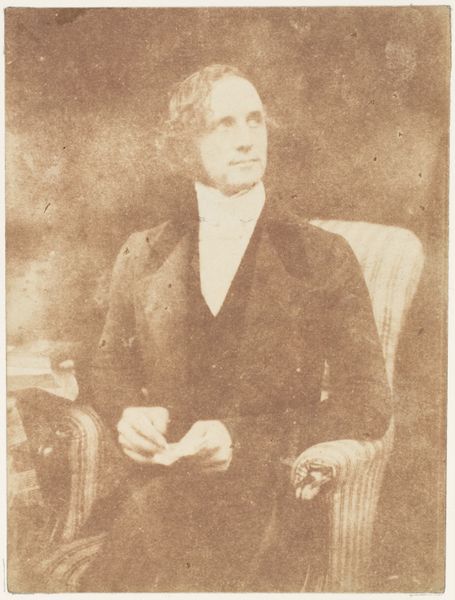

Dimensions: height 453 mm, width 368 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have William Bonnar's 1846 portrait of David Welsh, executed using a gelatin-silver print. Editor: The subdued tones create such a contemplative, almost melancholic mood. What was the typical usage of such images and processes? Curator: This was the early period of photography so creating images was really driven by documenting prominent individuals like David Welsh, who was a minister and academic, as well as recording the shifting societal structures during the Victorian era. Editor: Right, because capturing likeness through photographic means demanded significantly more equipment and labor, compared to drawings or engravings at the time, and served the very clear class distinction being established through consumer society and developing economies. Look at the subtle handling of light and shadow, defining the subject's face and clothing; it speaks to the mastery over a challenging, emergent technique. Curator: Absolutely. This image represents the growing interest in portraiture alongside photography, the tension it creates reflecting power, knowledge, and identity in rapidly transforming social structures and a quickly expanding British Empire. Editor: This print also raises questions about access and consumption: the chemical processes alone, who were these early photographers sourcing raw materials from, and what labour and logistics were needed in order to put those photographic emulsions onto silver gelatin paper to memorialize Scottish elite? It seems that through that early history of materials and equipment, so many contemporary processes become imaginable. Curator: That’s fascinating, contextualizing art production not just through an art historical canon but examining labor conditions and industrial manufacturing. It emphasizes how deeply entwined individual expression can be. Editor: It definitely enhances our understanding of both the art object and of cultural narrative. Curator: Thinking through how class operates makes us consider these questions too: whose stories get told, and through which media? Editor: Exactly! We begin to understand the social power inherent in artistic creation, even in what seems like a simple photographic portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.