Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 345 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

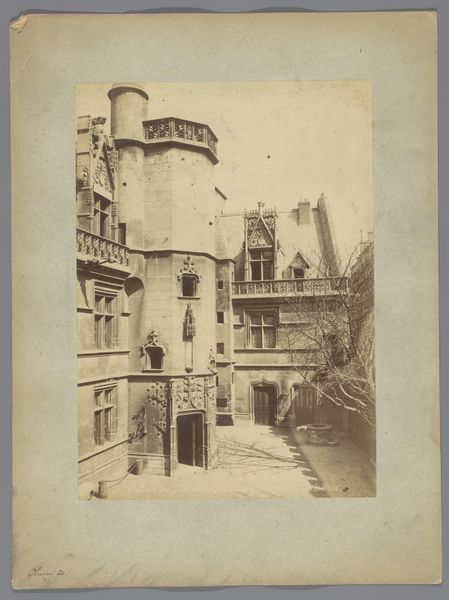

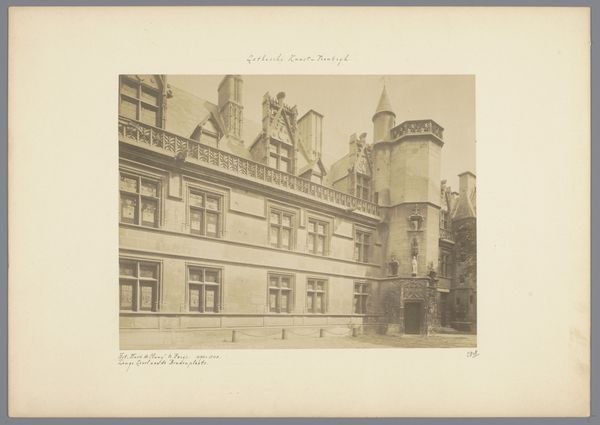

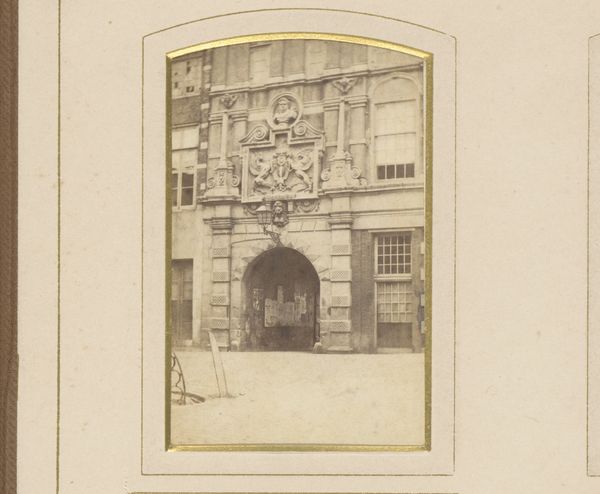

Curator: Here we have a photograph entitled "Gezicht op het Hôtel de Cluny te Parijs," dating from somewhere between 1850 and 1900. It's an albumen print by Médéric Mieusement, held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: My first impression is a kind of serene stillness, despite it depicting a city. The cobbled street, the aged stone—everything feels heavy and permanent. It’s a quiet photograph. Curator: That sense of permanence speaks directly to the social anxieties of 19th-century Paris. The photograph becomes a document, an archive of a quickly modernizing cityscape where historical sites, like the Hôtel de Cluny, become symbols of an imagined past that needs preserving and safeguarding from rapid transformations. Editor: I agree. I'm also drawn to the albumen process itself. The way it captures light, that sepia tone… it lends the image a certain nostalgic quality. Considering its production, albumen was inexpensive but very labor intensive, requiring meticulous coating of paper with egg whites, relating to questions of gendered labor in the art world. Curator: Precisely. And look closer – consider how the composition reinforces class divides. The high walls act as literal barriers, perhaps hinting at inaccessibility of culture to some and the protective barriers for others. We might ask who this “past” was truly for, and at whose expense were such legacies sustained. Editor: Right. And in terms of the building materials and construction—the rough-hewn stones, the visible joins… this is an image very much invested in displaying a pre-industrial mode of construction, even at a time of iron and glass in architecture. It presents the past in an idealized and palatable form for its intended audience. Curator: The light falls beautifully. We see shadows casting against a grand medieval architecture of a museum during a time of nation building. By reflecting on its place within both photographic and architectural history, it becomes easier to view as something more than just a city landscape—rather as something to be critically engaged with and historically examined. Editor: Definitely. The photograph offers an illusion of historical authenticity, masking the labor and the materials used in its creation, to naturalize not only its aesthetic but the very power structures it quietly upholds. Curator: Exactly. It's a layered piece that encourages reflection on both representation and reality in historical documentation. Editor: I agree completely, making you reconsider how images and labour operate on multiple levels to deliver a very crafted point of view, while pretending it isn’t.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.