print, etching, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

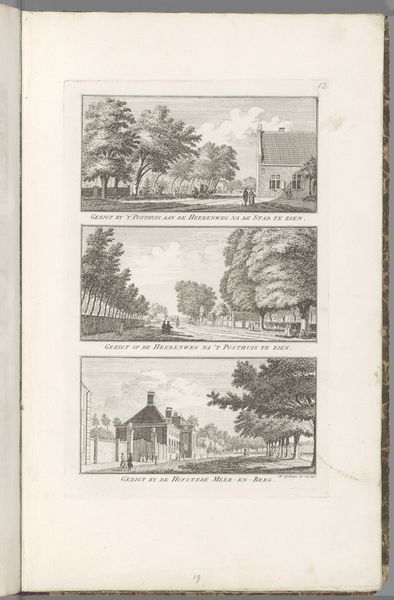

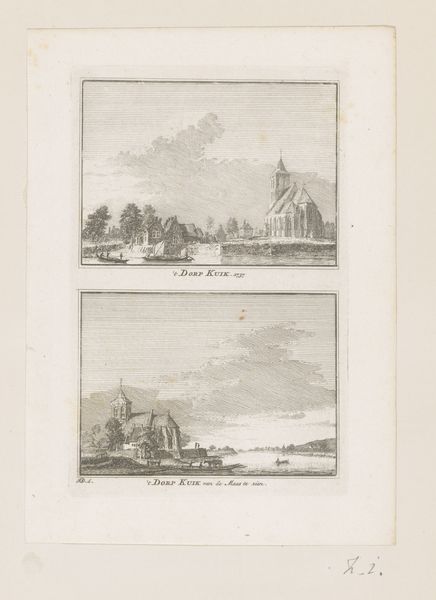

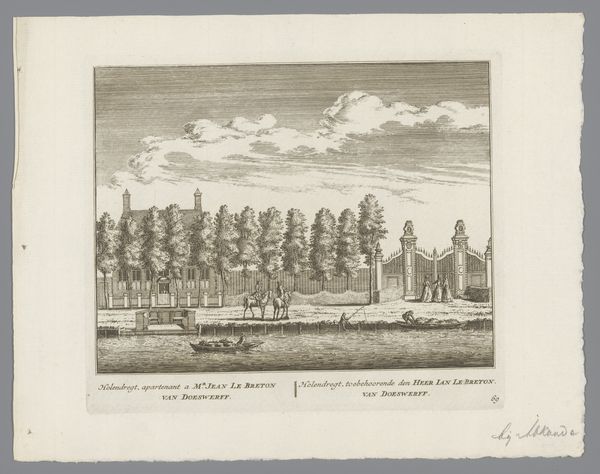

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 103 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

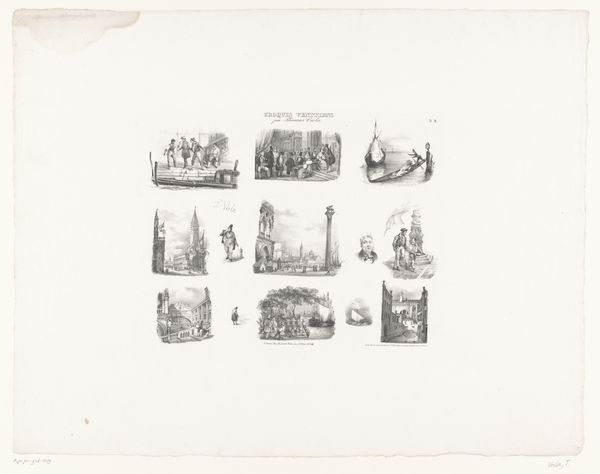

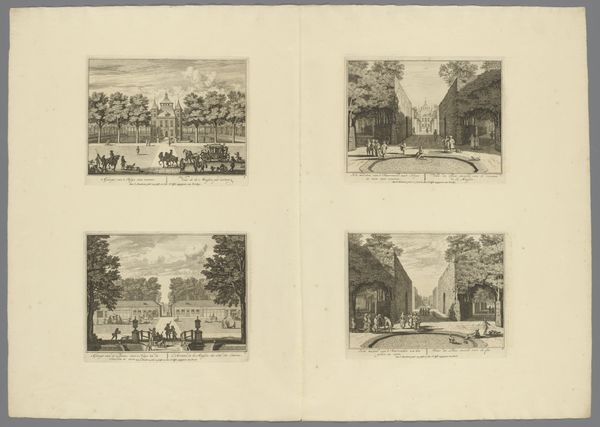

Curator: This print, "Twee gezichten op Kasteel Oud-Amelisweerd," made between 1773 and 1792, shows us two views of the estate. Hendrik Spilman used etching and engraving to create it. My first thought is about the painstaking labour involved in its making. Editor: It’s charming, almost like looking at dollhouses. There’s a peaceful quality to the symmetrical layout in the top image, although the lower scene is more like a direct glance into people's private lives. Curator: Absolutely. I see the labour not just in the artistic rendering, but in the construction and maintenance of Oud-Amelisweerd itself. Consider the gardens and architecture. This engraving documents the consumption practices of a wealthy elite whose financial fortunes provided opportunities for such labor. Editor: And the print is an interesting artefact for thinking about power and status during the Dutch Golden Age. These landscapes showcase the order, beauty, and privilege upheld in the Republic's class structure and society. These images are consumed by those already in power—demonstrating it. Curator: The artist would’ve had to possess knowledge of material production to translate the three-dimensional architecture and landscape into a two-dimensional printed image. Looking closely, we can identify differences in the etching and engraving, observing how Spilman combines the textures created by both to offer variation and nuance. Editor: How interesting that these aren’t just landscapes. They’re historical records shaped by distinct social and political motivations. Considering Spilman's era, these scenes likely present an idealized vision, reinforcing specific cultural values tied to land ownership and leisure. It even says on the print "Amelisweerd, as it appeared in the year 1672". So its likely documenting its image in relation to history. Curator: Indeed. I appreciate your focus on representation. Thinking about Spilman’s intended audience deepens our understanding, doesn't it? It transforms this seemingly placid scene into a complex record of artistic, manual, and intellectual labor bound by class. Editor: This makes me see more in what at first felt quaint—unearthing hidden meanings through different lenses. Curator: For me, tracing the printmaking process and acknowledging its function sheds light on the social relationships enmeshed within artistic creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.