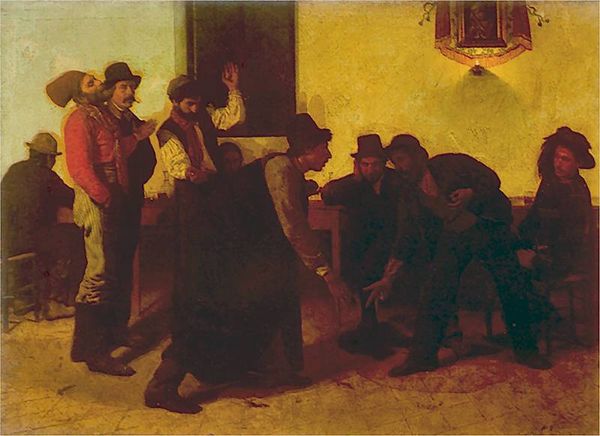

painting, oil-paint

#

figurative

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

realism

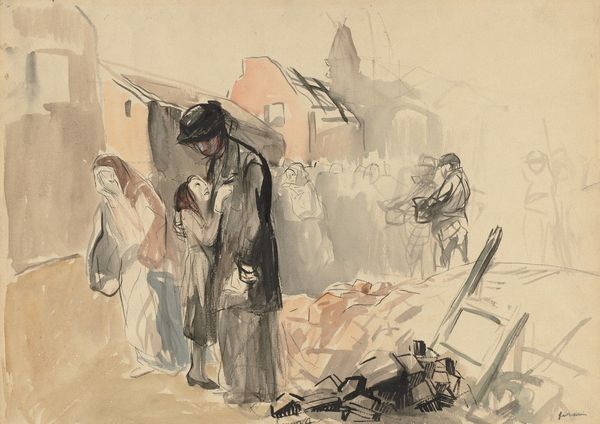

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Curator: Here we have Francisco Goya's "The Third of May 1808," executed in 1814 using oil paint. My first thoughts revolve around the socioeconomic climate that birthed this image, namely the French occupation of Spain. What's grabbing you initially? Artist: It's the electric agony! The stark contrast between the lantern's fierce light and the inky blackness, pinning those doomed souls like butterflies...It's raw, brutal. Curator: Indeed. Consider Goya’s process. Instead of romanticizing warfare, he zeroes in on its ghastly repercussions, using coarse brushstrokes and a subdued palette to underscore the event’s stark inhumanity. Look at the faceless executioners, rendered as a uniform killing machine devoid of individuality. Artist: Precisely. It's not about glorious battle. It’s the annihilation of the individual, distilled into one excruciating moment. The man in white, arms outstretched, he's a Christ figure, absorbing the horror for everyone else. Isn't it funny how that bright color spotlights everything around him, only deepening the surrounding darkness? Curator: Observe also the material reality of war present in the artwork itself. The rifles are a product of industrial progress employed here for death; that executioner's stance communicates the alienated labor of modern warfare where empathy and decision-making have been outsourced to technology and to statecraft. This implicates not just Napoleon's forces, but speaks volumes about systematic violence as a key mechanism for maintaining power dynamics in society. Artist: Absolutely, the arrangement feels so intentional. The emotional core explodes in the lit area on the left with these beautifully ugly colors and shapes, whereas there is total order and menacing lines on the right side. But doesn't it also ask us to contemplate human resilience, though? The courage in the face of obliteration? Goya's captured something profound about that flicker of defiance. Curator: And that defiance likely spoke volumes to a populace weary from war, seeking to reclaim their national identity after colonial disruption and internal conflict had torn families and the country as a whole. Goya understood his audience. His artistic choices reveal much about how power is communicated and contested on canvas during this critical moment of political, social, and economic change in early 19th century Spain. Artist: Thinking about that scream and about the quiet dark figures makes me question who gets remembered when these events pass. Is it the names on the military memorials? Goya has immortalized what that faceless man experienced, reminding me how our purpose as artists to amplify and witness can give shape to the dark chaos we can sometimes experience. Curator: A fitting reflection, and I appreciate how Goya's composition prompts discussion concerning who dictates history's narratives, while at the same time reflecting about violence as an enduring aspect of social systems, long after Goya and well into today. Artist: I agree; art that compels conversation—even centuries later—is perhaps the most powerful form.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.