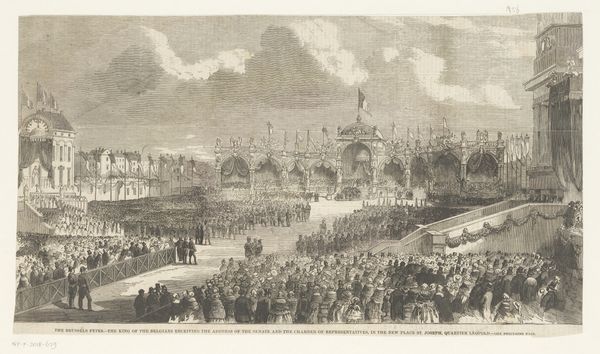

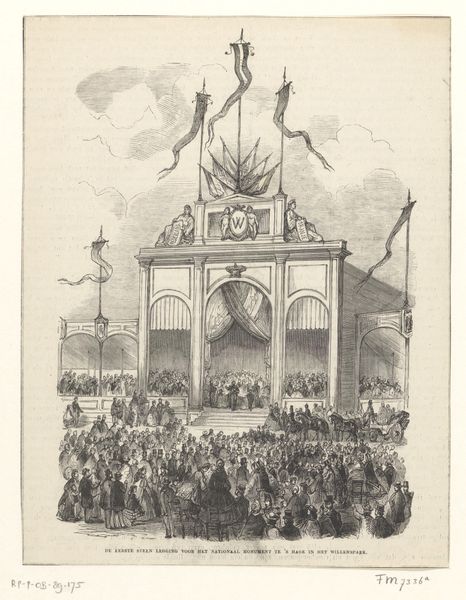

Koning Willem III legt den eersten steen aan 't Monument voor 1813. (17 November 1863) 1863 - 1865

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

lithograph, print

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 232 mm

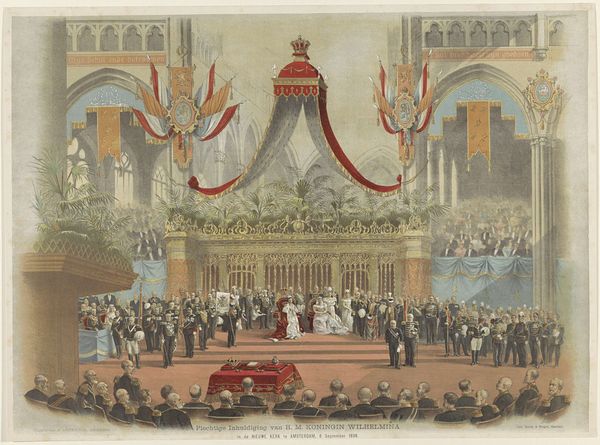

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So this lithograph, dating from between 1863 and 1865, captures King William III laying the first stone for the 1813 Monument. It's busy, lots of people, a real sense of civic pride I think, though the print itself feels... distant, somehow? How do you interpret this work? Curator: This piece really speaks to the constructed nature of national identity. Consider the choice of depicting the *laying* of the foundation stone. It's not just about celebrating a monument, but about the deliberate act of building a collective memory, a shared history. Who is included in this memory and, crucially, who is excluded? Editor: Excluded? I’m not sure I follow. Curator: Look at the crowd. Who are the visible actors in this historical narrative? The piece doesn't just commemorate an event, it actively shapes the narrative. How does the artist frame the relationship between the monarchy, the citizenry, and the very idea of Dutch identity? This act becomes symbolic – a top-down approach to collective identity, reinforcing the power structures of the time. What statements does the scale of the crowd, contrasted with the singular act of the King, make to you? Editor: I guess I hadn't thought about it that way. I saw the crowd as representing the nation, but it’s interesting to think about the power dynamic in their presentation, who gets to be at the forefront, whose actions are celebrated, and how the King and the royalist symbols serve to perpetuate those disparities. Curator: Exactly. And thinking about this as a lithograph – a readily reproducible image – speaks to the desire to disseminate this particular vision of national unity widely. What are the implications of creating these historical accounts with print? Editor: This makes me rethink the celebratory aspect – it's not just a record but a very intentional statement of power and historical narrative. Curator: Precisely. Art can serve the status quo, and the past is actively constructed, visually and ideologically. Always ask, cui bono?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.