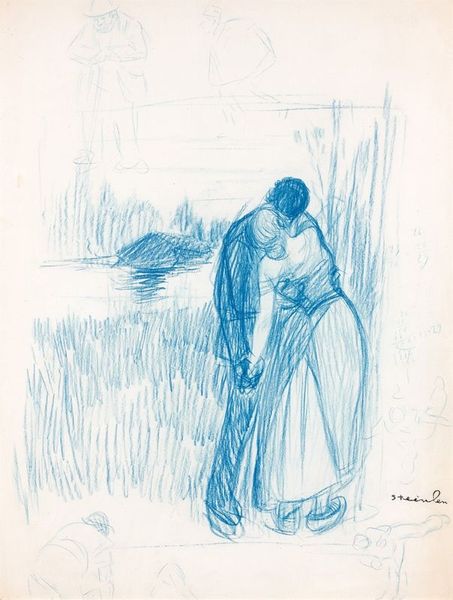

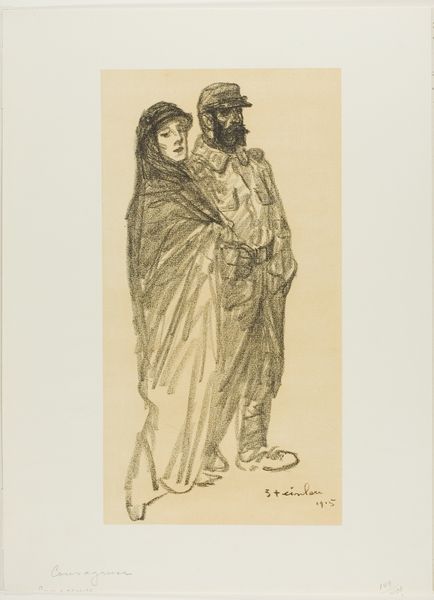

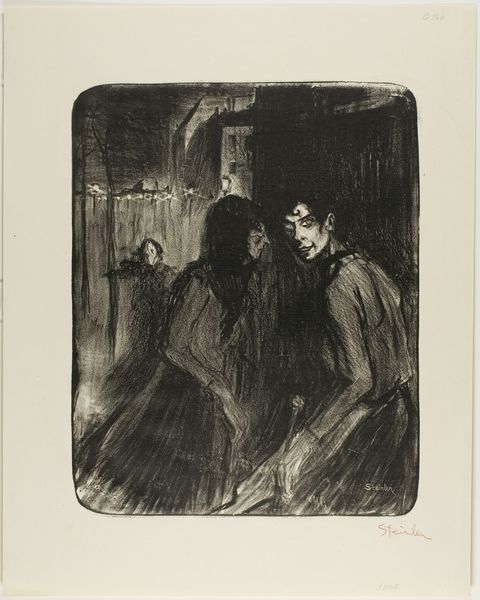

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

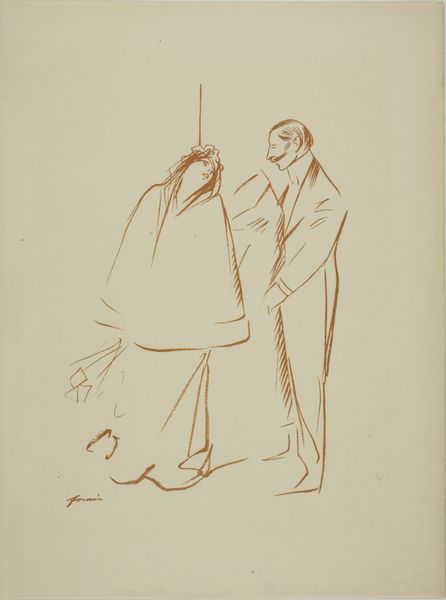

portrait

#

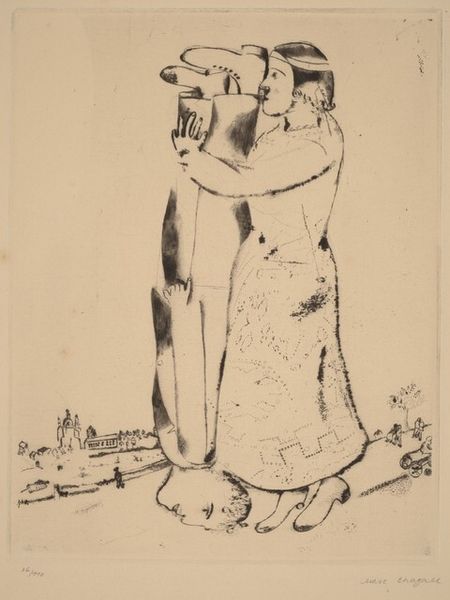

drawing

#

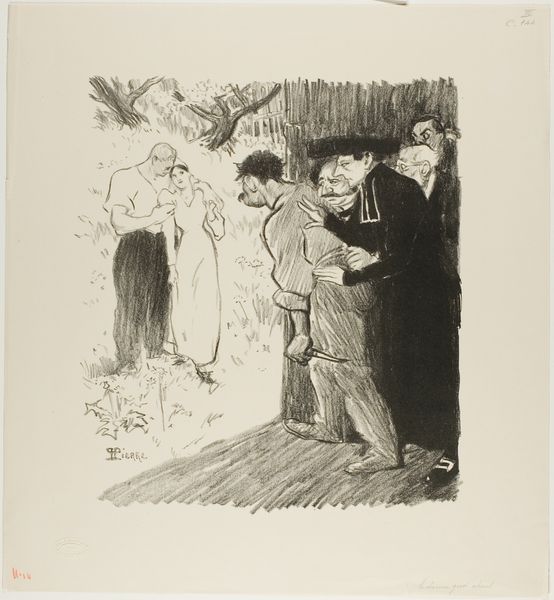

narrative-art

#

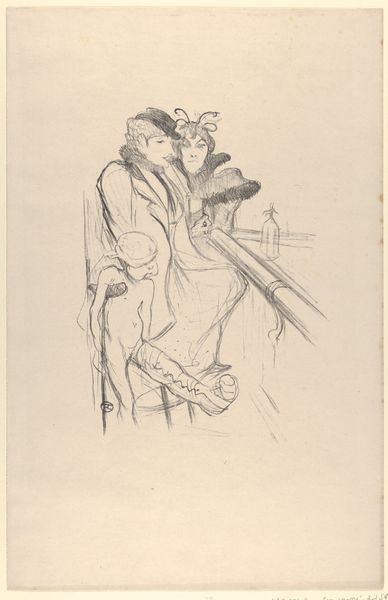

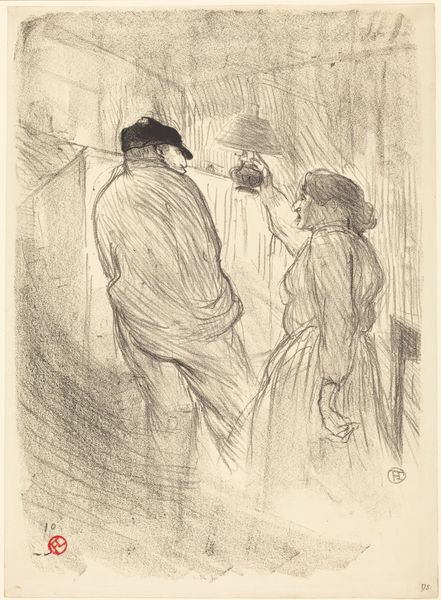

lithograph

# print

#

paper

#

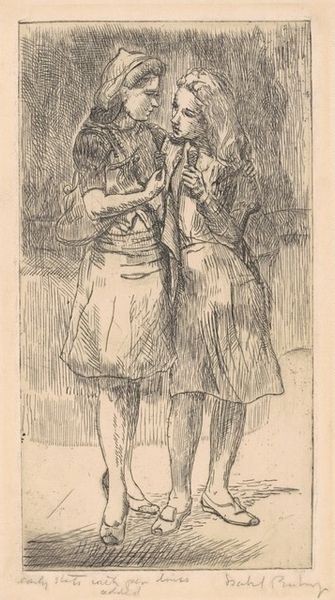

pencil drawing

#

symbolism

Dimensions: 333 × 280 mm (image); 548 × 382 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Thèophile-Alexandre Steinlen's lithograph, "Liberty's Last Refuge," created in 1894, hangs before us. What's your initial take? Editor: A somberness settles over me. The muted tones and stark portrayal of the working-class couple create an atmosphere thick with despair. There's an anxiety in the woman's eyes. Curator: It’s arresting, isn't it? To me, Steinlen captures that fragile moment of tenderness amidst what appears to be looming disaster. Her gesture, grasping for some invisible hope... or maybe at just him. I wonder if he can see anything more either. Editor: Absolutely. The lithograph acts as a potent commentary on social precarity. Consider the backdrop—the industrial landscape encroaching, almost suffocating. The male figure is clasping his tools like it's the last thread to their livelihoods, symbolizing the increasing pressures of industrialization and the struggle for survival in 19th-century France. Curator: It's almost brutal how simply Steinlen achieves this. The roughness of the lithographic lines feels incredibly intentional. And those heavy strokes...it makes it feels like this moment is incredibly weighty. Editor: Weighty, yes, and consider what’s missing. There's an unsettling blankness. He's forcing the viewer to confront the very real, yet often unseen, struggles of working-class people. Who suffers in pursuit of progress and prosperity? The gaze challenges us. What will *we* do? Curator: Gosh, that makes it even more devastating to observe, I think. It is calling upon us to *notice*, to not look away. To acknowledge what he already clearly knew. Art making isn't ever just art making. It can be about creating tangible change, even through witness. Editor: And there’s a subtle radicalism at play here too, humanizing the “Other”. Giving an identity. By granting them dignity on such a large, vulnerable, scale it forces engagement, as you said, Curator. Even today, centuries later. It still moves and provokes and sits with you like a cold hard stone. Curator: I appreciate that perspective, always so keen and insightful, Editor! It seems to be the mark of true art if something from so long ago can reach across the threshold and feel this powerful now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.