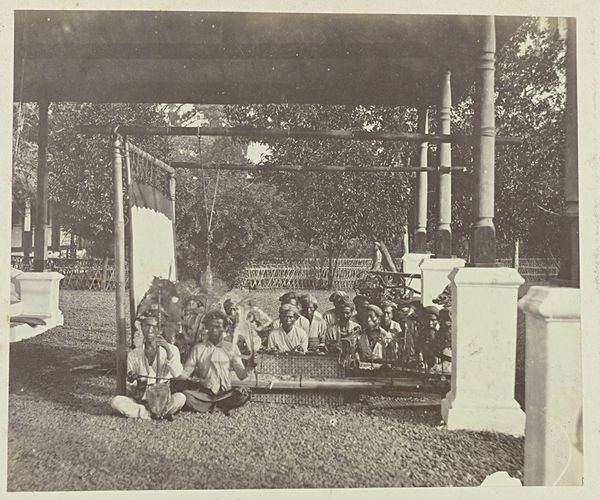

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

outdoor photograph

#

nature

#

outdoor photography

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Onnes Kurkdjian's gelatin-silver print, simply titled "Bali," was taken around 1900. What strikes you about it? Editor: Well, the composition immediately draws me in. The image pulses with a subtle energy—a crowd of faces peers out from behind a makeshift bamboo fence, with larger figures framing them. There's something almost theatrical about their presentation, yet raw and unpolished at the same time. Curator: Indeed. It's important to recognize the historical context of such images. Kurkdjian was Armenian, later based in Singapore. Photography in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was often entangled with colonial agendas. Images of places like Bali were circulated as ethnographic documents. We should ask whose gaze is privileged. Editor: Absolutely. This image can't be divorced from that history. Who were these individuals and how did they perceive the camera's intrusion? What did this picture mean to them? How did Western viewers receive it, especially in relation to prevailing colonial stereotypes? It's critical to avoid reducing this group to exotic objects. Curator: The children in elaborate costumes are intriguing, drawing focus and hinting at some sort of performance. Considering that photography from this period was commonly used to create visual typologies of othered populations, the festive look makes it challenging to define and highlights how performativity can challenge colonial views. Editor: And what are we to make of that rather bulky piece of equipment—possibly a loudspeaker—behind which part of the group is seated? It definitely anchors the photograph in a specific time while raising all sorts of questions about technology and cultural exchange. Curator: Right. Understanding this photograph demands a critical lens. Kurkdjian's "Bali" prompts reflections on image-making, colonial representation, and the challenges of intercultural understanding, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Precisely. It reminds us that historical photographs are more than simple documents; they are contested sites of memory, power, and meaning, all of which demands to be considered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.