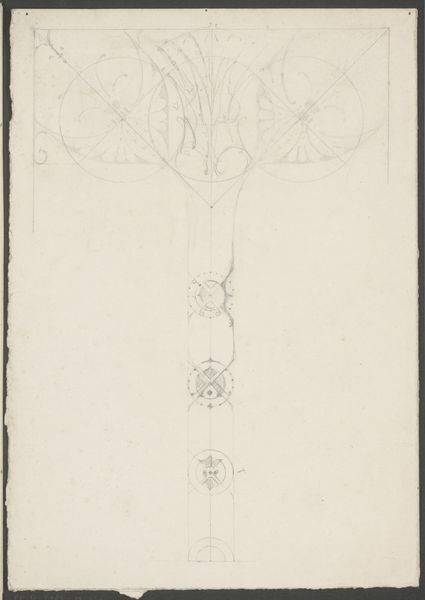

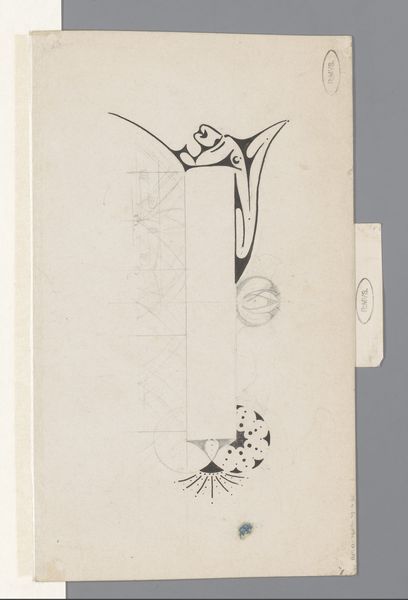

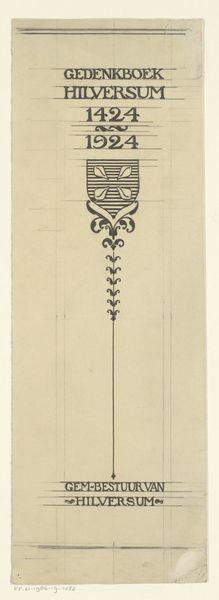

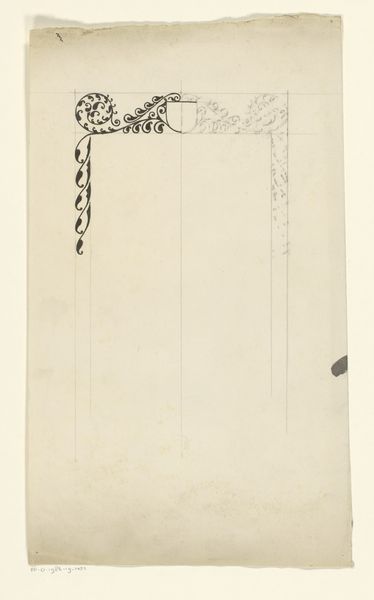

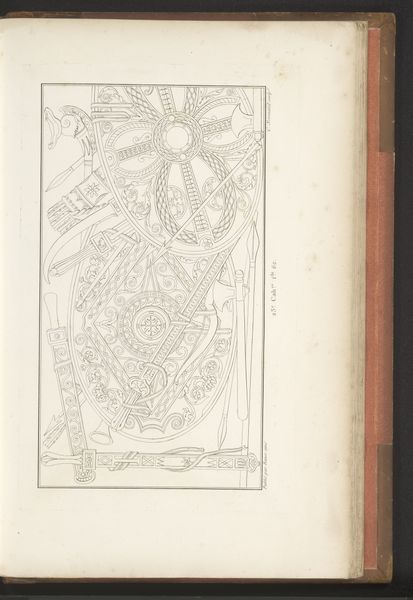

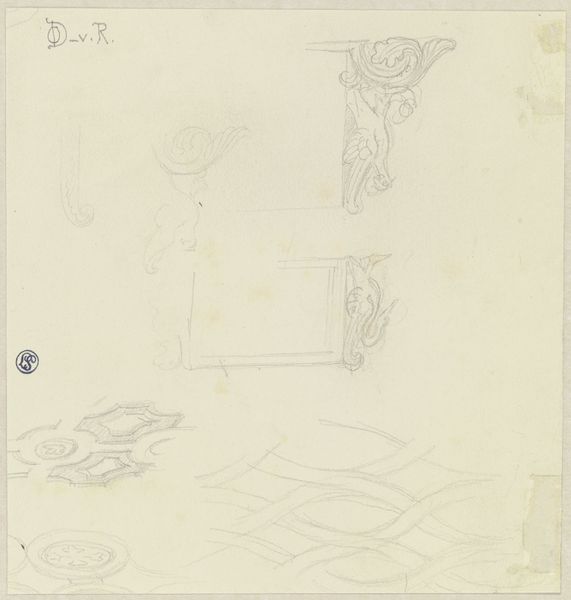

Ontwerpen voor een titelhoofd met een zwaan en bloem 1884 - 1952

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

drawing

#

art-nouveau

#

form

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

line

#

graphite

Dimensions: height 147 mm, width 203 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This drawing, "Ontwerpen voor een titelhoofd met een zwaan en bloem," or "Designs for a title page with a swan and flower," is by Reinier Willem Petrus de Vries, dating roughly from 1884 to 1952. It is graphite and pencil on paper. The design feels very ornamental and ordered to me. What are your thoughts on this work? Curator: Well, first, notice how this drawing encapsulates the core tenets of Art Nouveau: an almost obsessive dedication to natural forms married with geometric stylization. We see the swan, the flower, but they're rigorously contained within a framework of lines and repeated motifs. But, more importantly, I wonder how it can teach us about gender and power. Do you notice how this imagery connects to ideas of femininity at the time? Editor: I can see that... the flower and the swan are softer shapes. But how would this challenge existing notions of femininity? Curator: Absolutely. Yet think of Art Nouveau as a radical move against the industrial age's masculine aesthetic. It reclaims the decorative, typically coded as feminine, and asserts its power and complexity within the public sphere, therefore breaking the gender binary. Doesn't the prominent placement envisioned for the design--as the "titelhoofd"--also point toward subversion? Editor: Yes, I hadn't thought about it that way, that the decorative and "feminine" becomes assertive and strong. The intended placement of the artwork also contributes to its re-reading and challenges us to rethink gender roles during the Industrial Age. Curator: Precisely. By positioning these elements as the "head" of the page, De Vries elevates them, giving traditionally feminized forms intellectual weight. The fusion of swan and flower subtly declares independence and the desire for women's emancipation. It's a delicate revolution, rendered in pencil and graphite. Editor: This makes me consider the context of this art in terms of the women’s liberation movements of the period! I thought it was just decoration, but I was wrong. Curator: Indeed, there are deeper conversations occurring than meets the eye, the political undercurrents! Every careful drawing invites a critical understanding, doesn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.