Copyright: Public domain

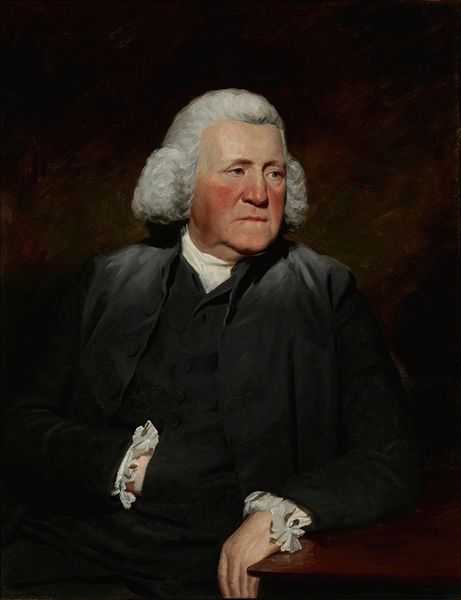

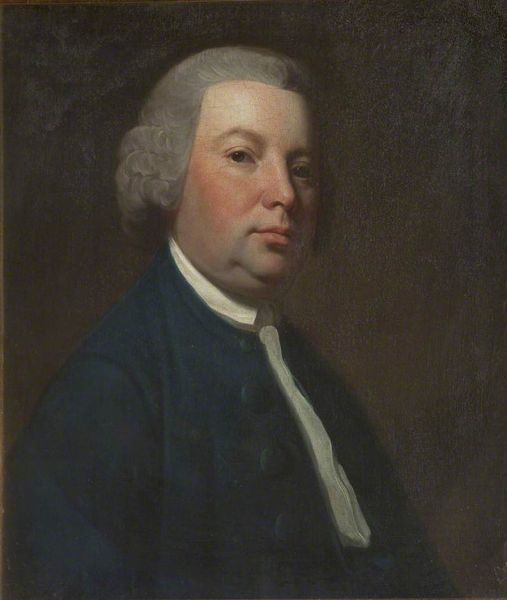

Curator: Oh, there’s something very quietly imposing about this one. Do you feel that? It's George Romney's 1772 oil painting of Abraham Rawlinson. He has such a knowing, almost playful expression. Editor: Playful? I see a man deeply entrenched within systems of power, gazing confidently outwards from his perch atop… well, likely colonial structures of exploitation given the period. The slight upward tilt of the chin reads more like arrogance to me than playful intrigue. Curator: Well, maybe it's the softness, the way the light plays on his face, almost luminous against that dark background. The wig, I'll admit, gives it a sort of performative seriousness, but those eyes… there's something gentle lurking, like a hidden joke only he is privy to. What do you make of the brushwork, so loose in some areas, yet quite defined in others, like in the face? Editor: The brushwork betrays the artifice inherent in portraiture of this era. Romney walks the line, depicting Rawlinson with the expected gravitas of the elite class through pose and composition, but the rendering feels almost too…human? See those rosy cheeks, the creases around the eyes; elements that both soften his features, but speak more subtly to a certain inherent… privilege? Rawlinson wasn’t just born with a silver spoon; the painting reminds me of the human costs embedded into such seemingly quaint, gentlemanly images. Curator: Yes, and yet, isn’t there a danger in reducing him solely to those power dynamics? Couldn’t we also read into this the vulnerabilities of being human? Look, the aging around the eyes is masterfully shown through very fine rendering...I almost think I see, in this image, not an allegorical villain but something close to what's known about his internal states... It feels incredibly moving. Editor: But isn't that empathy perhaps misplaced? A critical lens forces us to engage with these works not simply as character studies, but as cultural artifacts complicit within larger narratives. Ignoring the social context in favor of the individual pathos serves, I feel, only to perpetuate the problem. Curator: Fair, but maybe, just maybe, we can hold both truths, his individual complexities, and his implication within oppressive structures at once. I do find this quite moving. Editor: It’s a necessary tension, certainly. Reflecting on how art, even seemingly simple portraiture, encodes layers of complex historical data allows us to understand not only the aesthetic values, but ethical implications behind these images. Curator: Precisely.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.