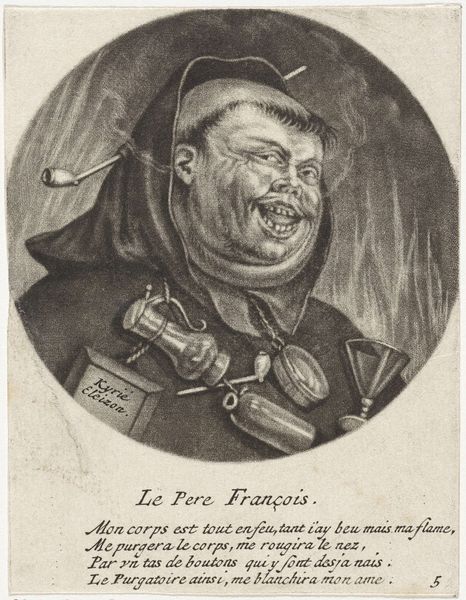

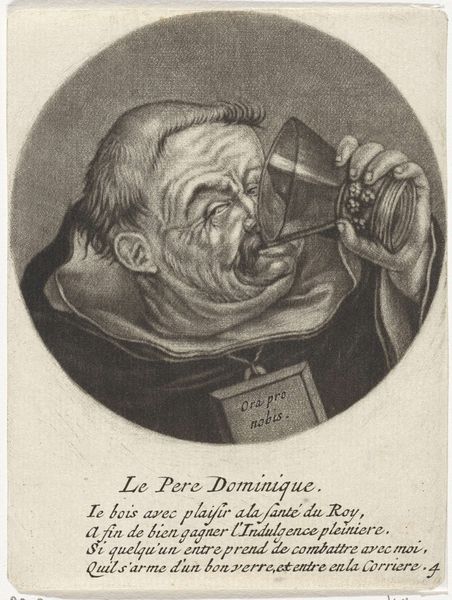

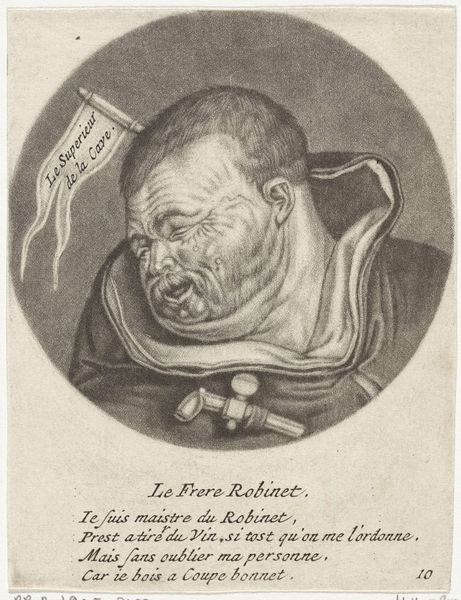

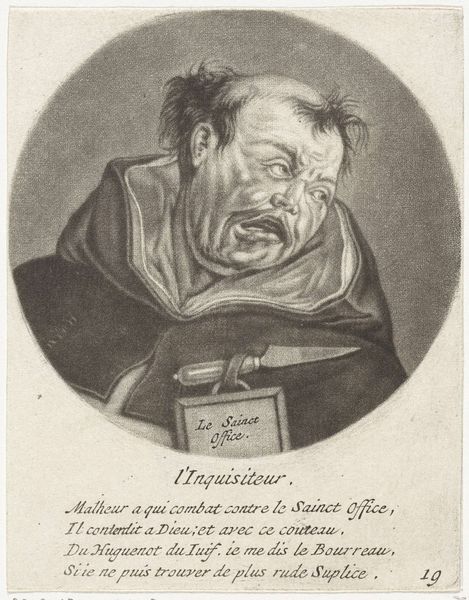

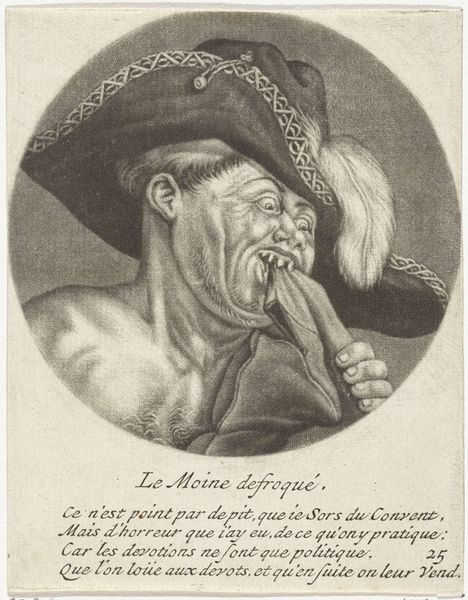

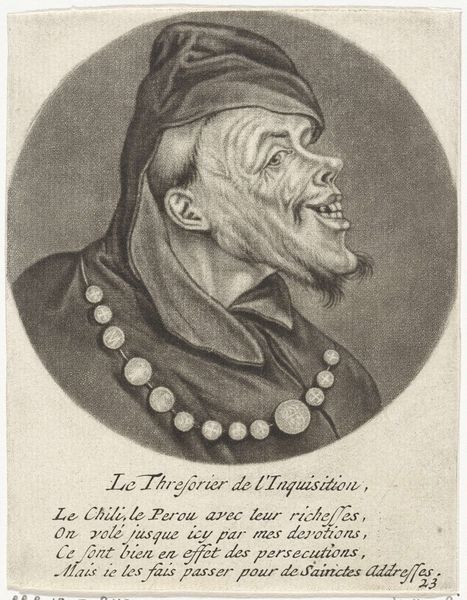

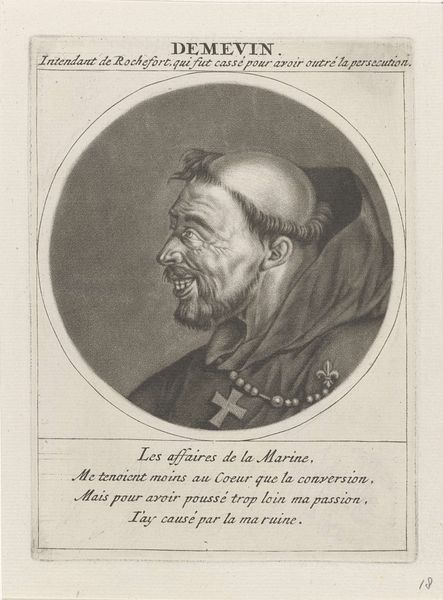

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

caricature

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

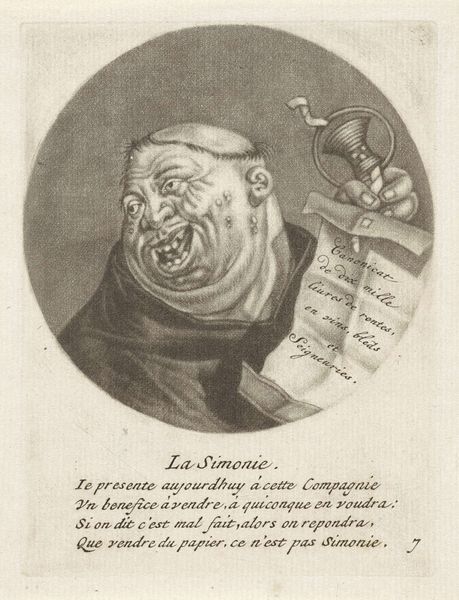

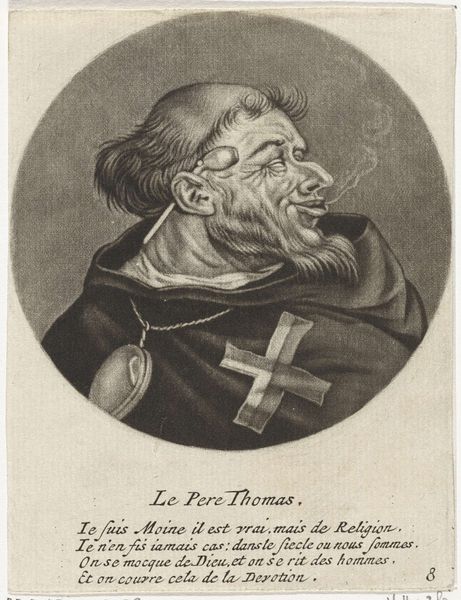

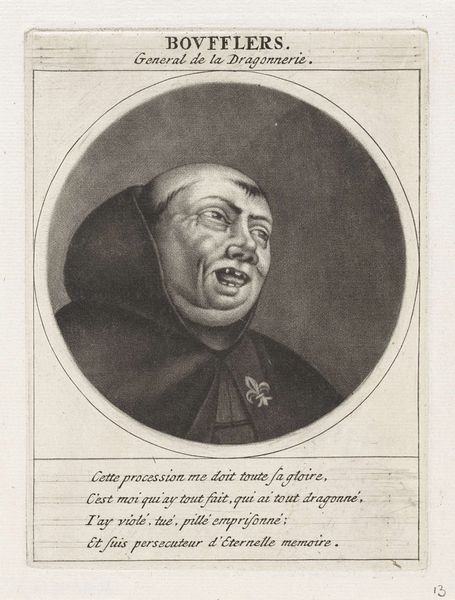

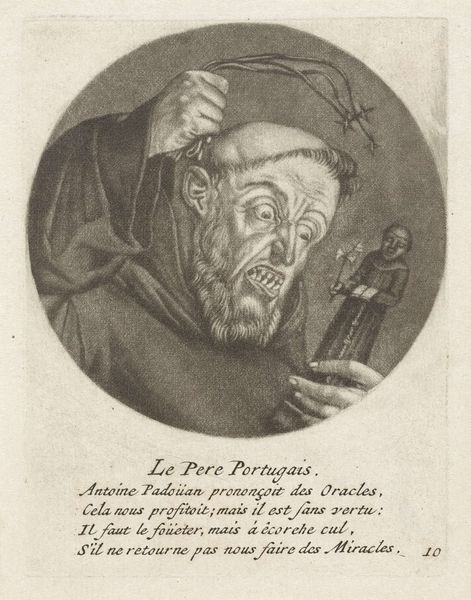

Curator: This intriguing print, held here at the Rijksmuseum, is entitled "Monnik met een zweep," or "Monk with a Whip," possibly dating from 1670 to 1724, and it's attributed to Jacob Gole. The medium is engraving, showcasing Gole's mastery of line work. What's your immediate take? Editor: Well, my gut reaction is a mix of amusement and unease. He looks like he's got a secret—a naughty one. It’s like peering into a hidden corner of human nature, all those scribbly lines seem to emphasize the folds in his skin. And the little pom-pom on his hood, oh I do love details. Curator: Indeed, Gole cleverly uses caricature to satirize religious hypocrisy. Notice the banner behind the monk's head that reads “La devotion Apparente,” or "Apparent Devotion." It’s a direct jab at performative piety within the church. Editor: Ah, so he's all show! Makes that squinty-eyed, knowing smirk even richer. I like the way the engraving gives texture to his robes too. They seem simultaneously plush and restrictive. And is that little cluster of what, burrs or thorns, dangling from the stick he’s holding? Curator: Precisely. It seems as though Gole used satirical prints like these to critique societal norms and power structures of the time. This particular print is ripe with symbolism, it comments on self-flagellation, contrasting the supposed religious suffering with genuine spiritual conviction, or rather the lack thereof. Editor: It feels incredibly relevant even now, doesn’t it? That performative piety still rears its head. But Gole does it with such... cheek. And the composition within the circular frame is masterful, drawing your eye to the face first, then letting it wander across all those wonderful little details. There's real bite here. Curator: Absolutely. "Monnik met een zweep" allows us a glimpse into a specific historical moment and an artist willing to challenge the status quo. It also asks how satire operates in relation to image making. Editor: And for me, the way it evokes such complex feelings. It makes you want to laugh, yet it leaves you with a disquieting question. Maybe that's the mark of true artistry. Curator: I agree wholeheartedly. It's a wonderful work to contemplate how the visual languages can carry nuanced critique and insight through the ages.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.