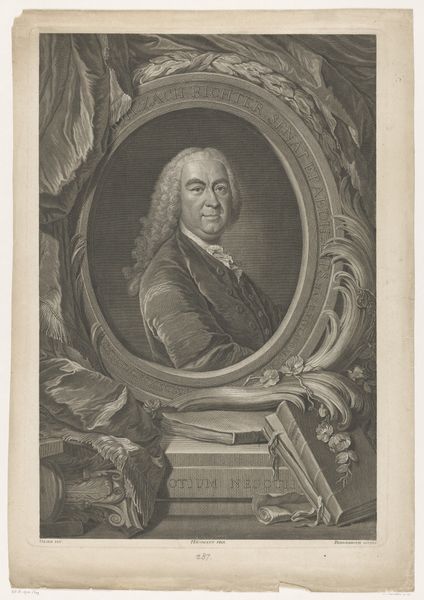

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

caricature

#

history-painting

#

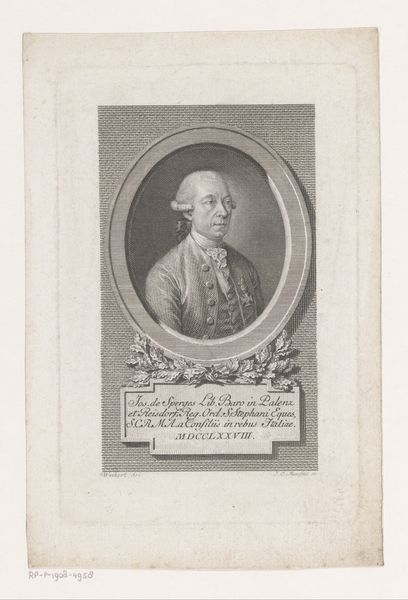

engraving

Dimensions: height 292 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jonas Haas’s 1747 engraving, "Portret van Joachim Werner von Negendank." Editor: Immediately, I’m drawn to the precision of the lines—you can almost feel the burin working the metal plate. The portrait has a severe elegance to it. Curator: Absolutely. Let's consider the socio-political context here. Portraiture in the 18th century functioned as a crucial tool for projecting status, solidifying identities linked to lineage and nobility, and propagating particular narratives of power. Haas situates von Negendank in an elaborate, Baroque frame above his name, birth, and death information, presenting him within a preordained, very constructed narrative. Editor: True, the engraving itself functions as a commodity—printed, distributed, and consumed within certain social circles. The act of creating these portraits also depended heavily on labor: the engraver’s skill, the access to materials like copper, inks, and presses, reflecting the economics of image-making in that era. And those elaborate borders suggest not just a frame but the cost and work that went into its execution. Curator: Indeed. Furthermore, consider the inherent power dynamics represented by such a portrait. Who gets remembered, whose image is disseminated and preserved? How does von Negendank's identity reinforce and resist societal norms through pose, clothing, even in the engraved script that surrounds him? It becomes clear how seemingly simple portraits perform cultural work beyond mere likeness. The coat of arms too reminds us of class identity and its role in legitimizing authority. Editor: It makes me think of how printmaking democratized portraiture somewhat. Though access was still limited, the ability to reproduce and distribute the image more widely shifts the dynamics of display. Think about how many people are included in this means of distribution - beyond just its consumption. The portrait speaks less to individuality, but the industry of image making. Curator: Precisely. And from that vantage, we can scrutinize how images operate not as transparent reflections, but as active agents perpetuating narratives of power that influence and structure reality, not only then, but to this day. The tradition persists in the art world, often concealing power. Editor: A lot to unpack in this simple-seeming engraving, reflecting not only individual status but the broader mechanics of visual production and social relations. Curator: Yes, the historical context adds layers of significance, encouraging a deep look at identity and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.