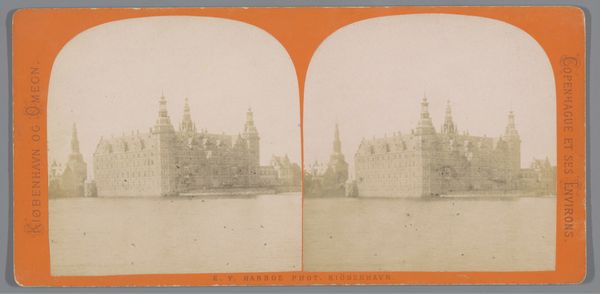

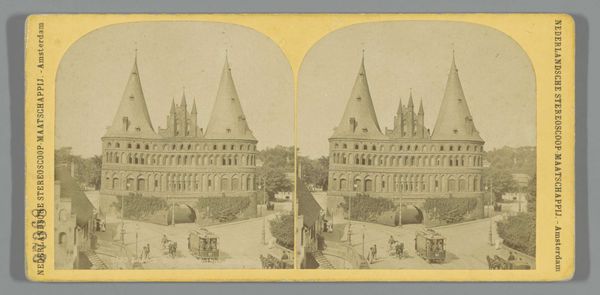

Gezicht op slot Frederiksborg in Hillerød, Denemarken 1873 - 1883

0:00

0:00

edvardvaldemarharboe

Rijksmuseum

print, photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 75 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a stereograph, “Gezicht op slot Frederiksborg in Hillerød, Denemarken”, placing Frederiksborg Castle within its watery context. It dates from 1873 to 1883, and it looks like it involves a photographic print, perhaps touched up by hand, created by Edvard Valdemar Harboe. It has an undeniably romantic, almost wistful atmosphere. What particularly stands out to you about this piece? Curator: For me, this image speaks volumes about the rise of photography as a *means* of both documenting and marketing place. This stereograph wouldn't just function as a pretty souvenir; it embodies industrial advancements that cheapened image production and its relationship with expanding markets. The division into two slightly offset images highlights the production process and begs us to see beyond the mere landscape to the infrastructure enabling its distribution and consumption. Think about the labor involved in making prints like these—a significant factor at the time! Editor: That’s interesting. I hadn't really considered the labour involved, more the photographic process. Do you think the 'landscape' genre played a part in the material consumption as you suggest? Curator: Absolutely. Landscape imagery became incredibly popular with industrialization and urbanization, which provided a window back to the country for an increasingly metropolitan population. The commodification of "nature," neatly packaged and sold, masked the industrial realities changing both town and country at the time. This romanticized view only served to conceal this shift. What materials were considered “worthy” of depiction here also warrants a critical examination – notice how Harboe doesn’t turn his camera to labour itself! Editor: So, it's less about the artistry and more about its role in this consumption cycle? Curator: I would not discount its artistry altogether, more so understand the cultural values that conditioned what constitutes “art.” I would also draw a strong line that asks us what sort of ideological position is being consumed and projected through this art. We see that landscape art is far more tied to labor and trade of visual commodities than it initially appears. What have you gathered from our talk? Editor: I've begun to consider not just what's *in* the image, but the material reality of its making, its dissemination, and its intended audience, helping me to approach artwork with a material-oriented attitude. Curator: Precisely, thinking about *how* and *why* art is produced really challenges what we consider worthy to see and believe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.