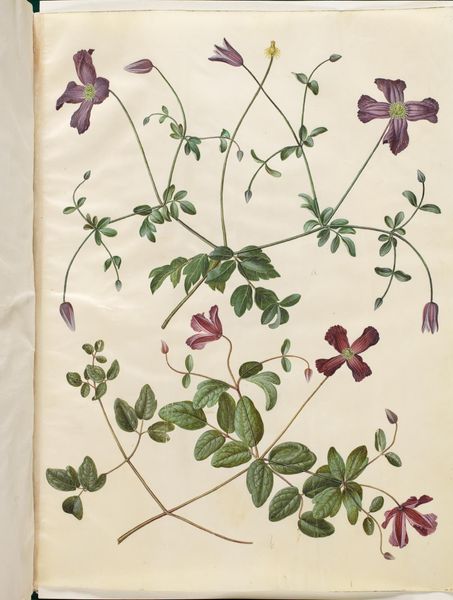

Aquilegia vulgaris (almindelig akeleje) 1649 - 1659

0:00

0:00

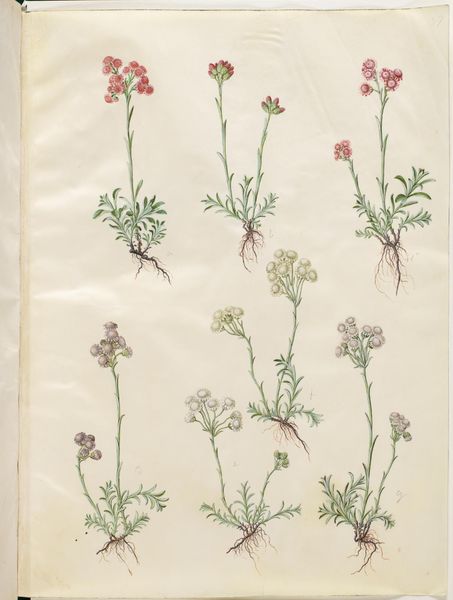

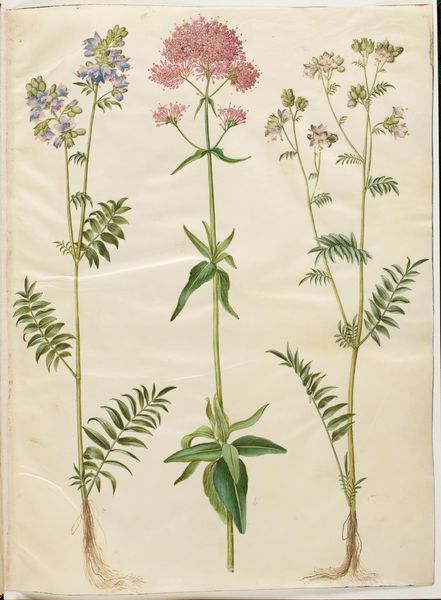

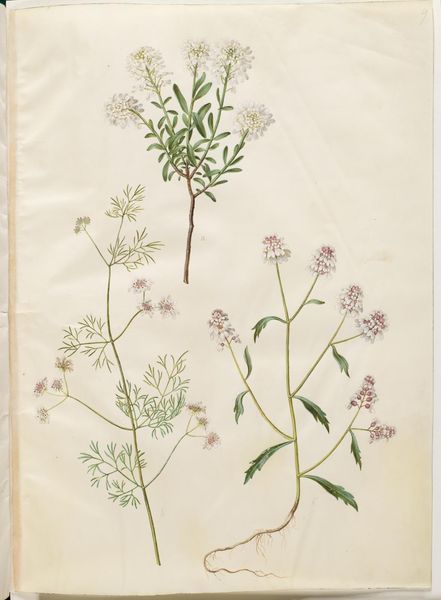

drawing, tempera, gouache, watercolor

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

tempera

#

gouache

#

watercolor

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 505 mm (height) x 385 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: At first glance, this botanical illustration seems like an exercise in refined observation, perhaps a bit clinical. Editor: I agree, there’s a coolness to it. But I see so much more, perhaps owing to its very nature as an art object: "Aquilegia vulgaris (almindelig akeleje)" by Hans Simon Holtzbecker, created sometime between 1649 and 1659, and it’s currently housed at the SMK, the Statens Museum for Kunst. Holtzbecker employed tempera, gouache, and watercolor in its making, offering us a glimpse into the scientific methods intertwining with artistic production of the Baroque era. Curator: Yes, the medium itself tells a story. These weren't just paintings; they were often commissioned scientific studies. How were such botanical drawings produced, consumed? Were these luxury objects for the wealthy, offering status, or useful tools for apothecaries and doctors? The detail in the roots particularly points to medical applications. Editor: Exactly. And considering Holtzbecker’s position, possibly working for royalty, it’s likely these served multiple purposes. Art often fulfilled multiple roles. The choice of such costly pigments is evidence. They would likely have served not just as records of the species, but perhaps as emblems of status. It gives us insights into consumption patterns in royal courts. Curator: You are correct! And consider the cultural understanding of these plants in the 17th century. What role did gardens play? How were plants understood within the broader social and political context of the time? What does this level of specificity suggest about the value of observing, documenting, and classifying the natural world? This work then offers insight into production: the skills and labor involved. Who ground those pigments? Who prepared the vellum? It expands into considerations of consumption: patronage and audience. Editor: Thinking about our current moment, steeped in mass production, looking closely at something handcrafted like this— reveals much about what has been lost or what has transformed across these centuries, and what it can teach us today. What kind of world produced something with such care, time, and dedication, what were the socio-economic realities behind this artwork? Curator: A final consideration on its future: How can a work like this reframe our view of art's purpose beyond mere aesthetics? And, equally important, what can this teach us about the natural world that we seem intent on destroying, altering, and replacing, at least on a broad, almost geological, scale? Editor: I will think on that as I explore my neighborhood garden later today. I will keep an eye out for Colubine flowers...

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.