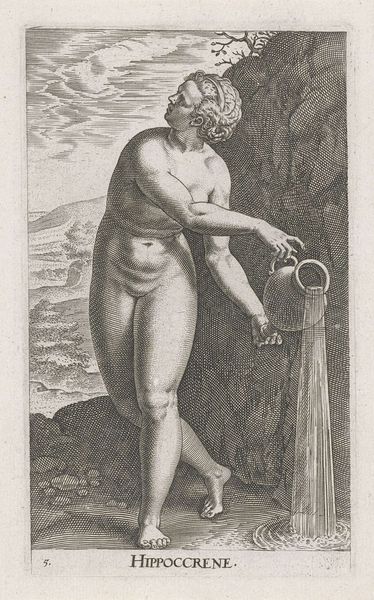

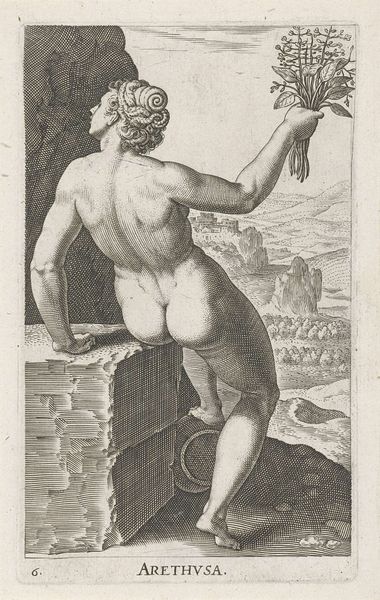

Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 101 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Waternimf Garga," an engraving from 1587 by Philips Galle, housed at the Rijksmuseum. The starkness of the engraving is striking, how the details are rendered using only lines. What do you make of this piece? Curator: The appeal lies in examining the means of its production: engraving. Look at the repetitive, meticulous labor involved. We also need to consider the role of prints in disseminating imagery and ideas in the 16th century. Was this print intended for an elite collector, or broader distribution? What impact would its circulation have? Editor: So, you're saying the *how* it was made, and *who* it was for, are key to understanding it? More than, say, the allegorical figure itself? Curator: Precisely! The depiction of the nude nymph is not just about beauty or classical reference; it speaks to the evolving market for art and the demand for such images, transforming classical allegory into something akin to early modern decor. Galle essentially mass-produced art for the burgeoning middle class. What does the fact that she’s emptying water tell us in light of this material context? Editor: Maybe water is like ideas being spread, something necessary being mass produced? Curator: Exactly. The engraving’s stark contrasts might highlight the accessibility of this previously rarified theme: consider the cost of oil paints. And its place in the Baroque movement. The Baroque style’s inherent theatricality aligns neatly with a kind of production aimed at grabbing your attention to consume art like a product. Editor: I never thought about art in terms of production and consumption before! Curator: Thinking about it through the lens of material production really challenges our usual ideas about art history, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.