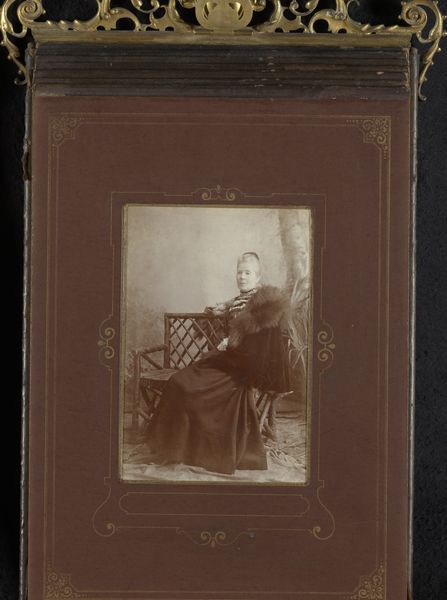

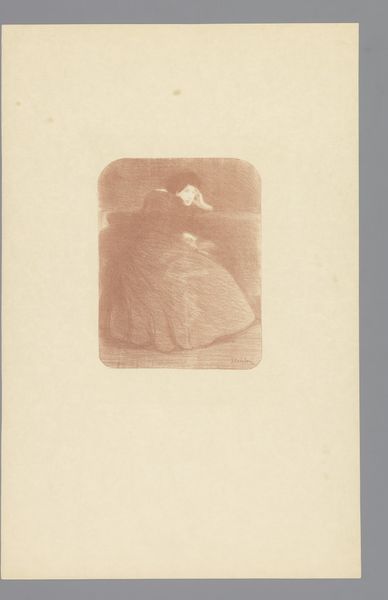

photography, albumen-print

#

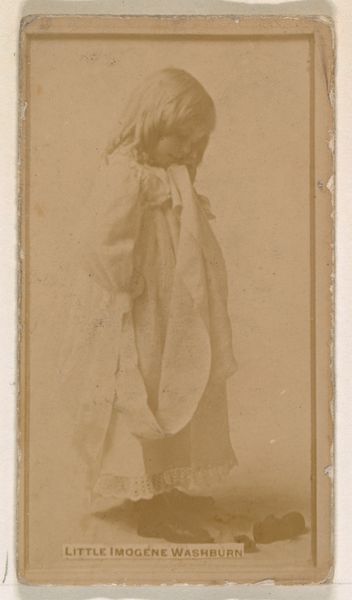

portrait

#

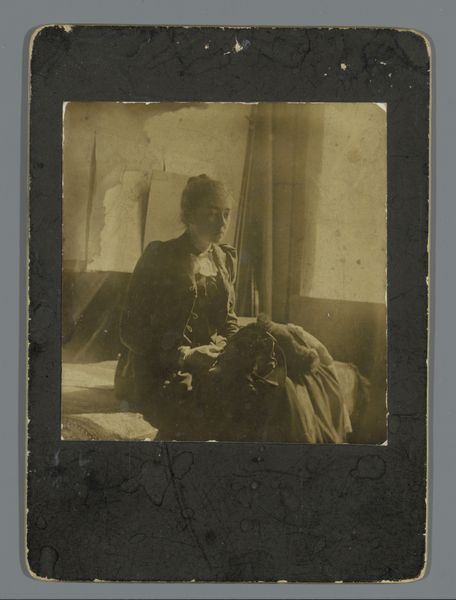

still-life-photography

#

pictorialism

#

photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 142 mm, width 93 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this "Portret van een vrouw met bloemen" – "Portrait of a Woman with Flowers" – attributed to Arthur Esme Collings, an albumen print from sometime between 1890 and 1900. It's such a striking piece of pictorialist photography. Editor: It feels intensely melancholic to me. The muted tones, the woman's downward gaze… There's a sense of heavy introspection and constraint that makes me think about societal expectations. Curator: I think your intuition is spot-on. Pictorialism, which really rose in popularity at this time, aimed to elevate photography to the level of art by mimicking painting and etching. These images weren't just snapshots; they were carefully composed and often manipulated to convey a specific mood or narrative. Editor: Right, and that manipulation is key. The woman here, formally dressed, seems burdened, almost concealed behind the enormous bouquet she’s holding. The flowers, intended as beautiful, become this barrier—a visual representation of how women were often seen as decorative objects first. It is a still life photography Curator: It is a poignant critique, whether conscious or not. You see this style of portraiture quite frequently during this era, reflecting a complex intersection of artistry, commercial demand, and societal norms regarding gender and representation. These are never neutral images. Editor: Never. This image speaks volumes about the performance of femininity. Her averted gaze and tight grip on the bouquet also evoke ideas of self-possession and emotional vulnerability, all at once. You see so much control and composure, but beneath it, is there perhaps resistance or, at the very least, unease? Curator: These albumen prints also served a very social purpose; being included in albums, circulated within families and communities. These were often presented as a declaration of status. Editor: So this photograph goes beyond mere individual representation. It captures a specific cultural moment, and makes visible its complexities surrounding class, and what was regarded as "high art." What lingers for me, in the end, is that subtle unease and questioning of her identity. Curator: Absolutely. It provides insight not only into the art of photography at the time, but also, into the world this woman inhabited, and it speaks in whispers still today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.