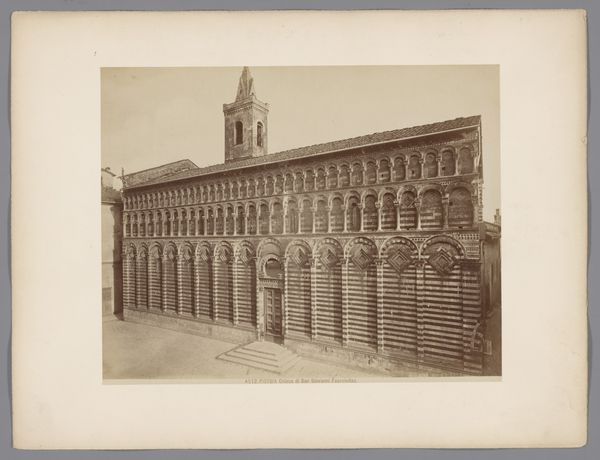

photography, albumen-print, architecture

#

sculpture

#

landscape

#

photography

#

islamic-art

#

albumen-print

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 245 mm, height 206 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What an evocative image! This is Giacomo Brogi's "Kloostergang in de kloosterkerk van Pavia," taken between 1864 and 1881. An albumen print capturing a cloister in all its geometric beauty. Editor: Yes, it's quite serene. There's something about the repeating arches and the muted tones that gives it a sense of quiet contemplation. The lone figure enhances that, adding scale to the vast space, while its materiality shows age and craft in the details of the brickwork. Curator: Indeed. Considering the period in which it was created, the photograph presents us with a view into the convergence of spirituality and power structures during the Risorgimento. The photograph hints at the Church’s position within the rapidly changing social and political landscape of a newly unified Italy. Editor: Absolutely. I am also interested in how that’s all built. The materiality of the structure — stone and light rendered visible through the craft of albumen printing. Brogi clearly understood the alchemical process of the darkroom, of imbuing a sheet of paper with architectural presence, as a manufactured article to be consumed by bourgeois collectors of souvenirs, an instance of early photographic reproducibility. Curator: That's a crucial point to highlight. And it is worth noting the intersectional forces, between sacred space and the rise of industrial picture production. The role of photography as not just an observer but also a participant in reshaping our perception of faith and community during Italy's political transformation cannot be overlooked. Editor: And also a shaper, given its scale: you have to consider where the materials come from, how labor gets applied, and the social networks in place that create value that didn’t exist before Brogi decided to haul his equipment out to a cloister and click. Curator: The composition also frames interesting considerations. How does the inclusion and implied role of religious figures impact viewers in various cultural spheres and socio-economic standings? Editor: The lone figure becomes almost a prop, I feel like, used to add an important feature to his print. Photography is just a complex mediation between labor, light, materials, time, money, all captured within these rectangles for consumers. Curator: Absolutely. It challenges the conventional lens, forcing us to analyze not only the artistic representation but the deeper connections to the human element and global power dynamics present within its composition. Editor: It reframes how we engage with the intersection of architectural space, its making, its inhabitants and mass image production— a constant dance between what’s built and what it makes visible, what labor it conceals, or reveals.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.