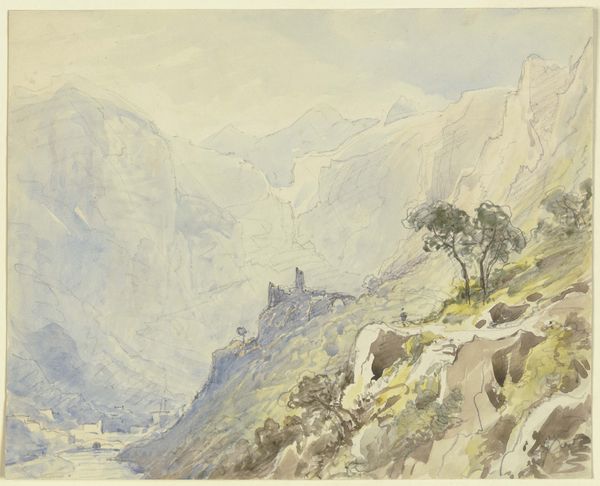

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 321 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I’d like to introduce Willem Jan van den Berghe’s "Berglandschap," created in 1869 using watercolor, and rendered in plein-air. Editor: It feels like an assertion of dominance, doesn't it? This colossal mountain range looming, the water raging through the rocks—a celebration of unbridled power. Curator: I find it masterful how van den Berghe contrasts textures. Notice the craggy faces of the mountains against the smooth flow of the water. He skillfully uses watercolor washes to give the mountains their tremendous scale. The composition uses subtle changes in value and carefully modulated light to show the rugged natural formations. Editor: Speaking of modulation, I’m particularly drawn to what’s missing. Who had access to this vista? During a time when leisure travel was deeply segregated along economic, racial, and gendered lines, we must consider how nature itself became another marker of privilege. Whose stories are obscured by these pretty vistas? Curator: An astute point. The social context of landscape art definitely shapes its meaning. But isn’t there an aesthetic appeal here beyond socio-political factors? Look at the artist's control of the medium: the layers, the blending. Observe how the soft, diluted strokes give the impression of atmospheric perspective and immense space. Editor: No doubt. The skill is evident, even captivating. But to ignore the way Romantic landscape art has often served to legitimize notions of colonial conquest or nationalistic fervor? The “natural” world often provides the justification of so-called inherent rights to domination and possession. Curator: Granted, nature’s allure can sometimes be deployed for problematic means. Yet, I still see the interplay of light and shadow as speaking to fundamental aspects of the human experience. Consider the composition in terms of binaries, light and dark, form and flow. This speaks to a need for structure amid ever-present dynamism. Editor: And those oppositions, structure vs. dynamism, nature versus humanity are never equal, aren't they? What does it mean when nature—pristine, untouched, idealized as the Romantics wished—became something separate from and subservient to human intention? Curator: Food for thought indeed. The act of creating this watercolor on-site, of trying to capture this grand vista – does point to this interplay. Editor: Agreed. Perhaps it is a constant negotiation—looking for both control and harmony amidst nature’s immensity, while being deeply cognizant of historical power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.