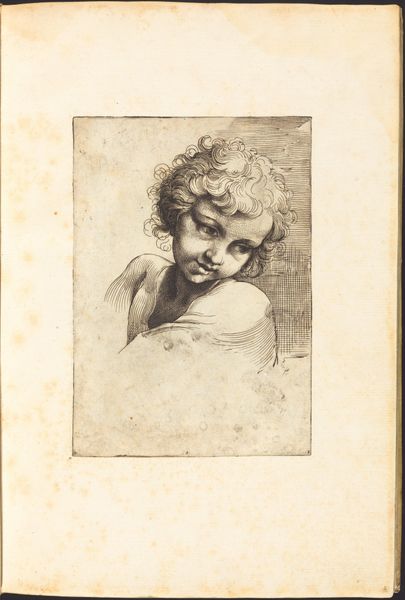

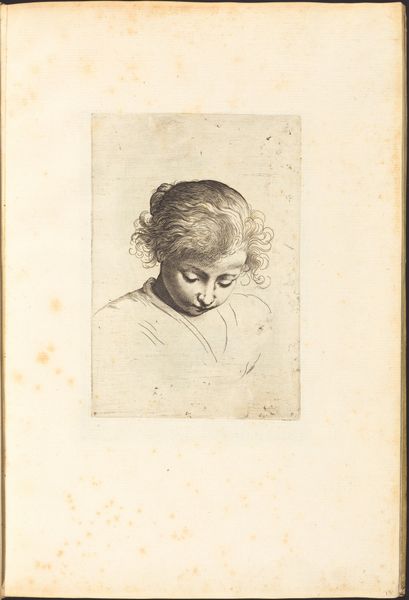

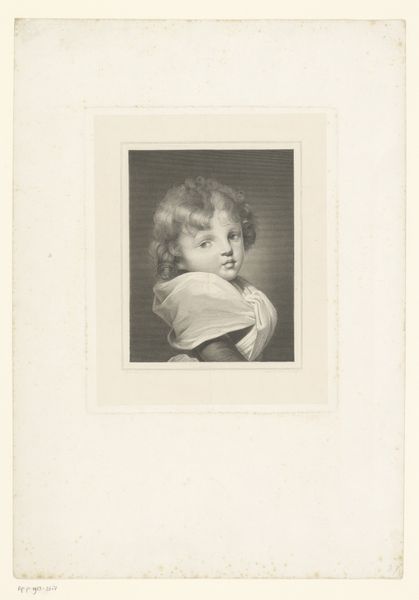

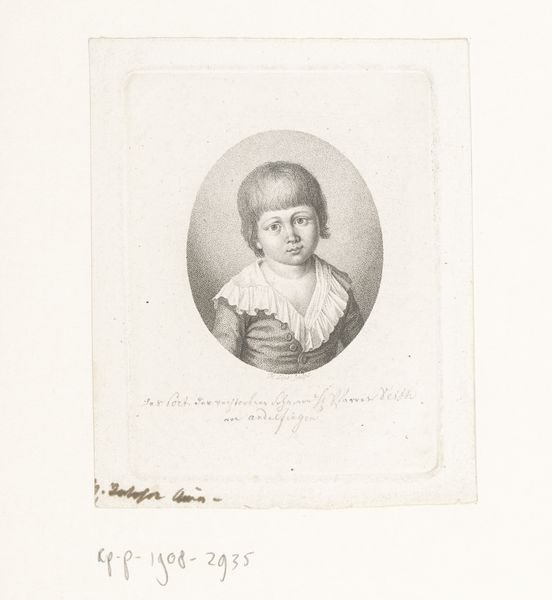

print, intaglio, paper, engraving

#

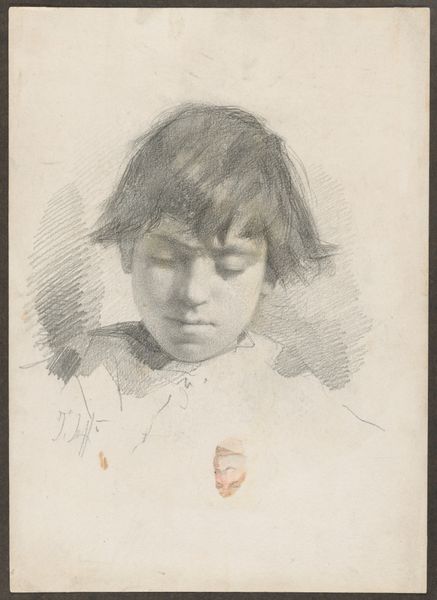

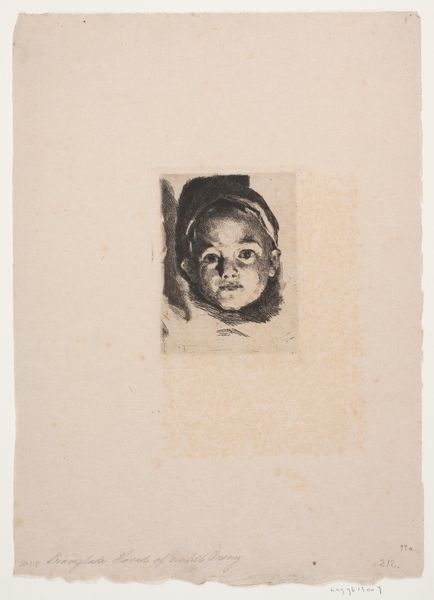

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Look at this fascinating intaglio print! It's called "Print from Drawing Book," created by Luca Ciamberlano sometime between 1610 and 1620. What do you make of it? Editor: The first word that comes to mind is innocence. But looking closer, there's also an almost melancholic weight to those eyes, those chubby cheeks. The rendering is incredible. Curator: Ciamberlano was working during a period where the concept of childhood was, in a way, being 'invented.' Prior to this, children were often viewed as miniature adults, rather than beings with distinct developmental stages and specific needs. Editor: Absolutely, the image embodies symbolic notions of purity and potential. Note the softness of the line, particularly in the wisps of hair, juxtaposed against the harder lines defining the eyes and mouth. Curator: I wonder if this print was made as part of the larger discourse about familial legacy. Think of the patronage system: having a male heir was exceptionally important and so depictions of children were often bound up in larger anxieties and power dynamics. Editor: That's insightful. I was more drawn to the recurring motif of infants or putti in Renaissance art. It draws on Classical associations, almost like a cultural memory, but filtered through the lens of Baroque sentimentality. What is he trying to convey about universal humanity through the eyes of a child? Curator: It could also speak to the politics of representation at the time. Children, especially in wealthy families, became powerful symbols, extensions of their family’s influence. Depicting them was strategic. Editor: Yet there’s also something deeply human about it, stripped bare by the simplicity of the medium. We see aspects of ourselves reflected. This image is about hope, legacy and something fundamentally delicate. Curator: It’s amazing how a relatively small print on paper from the 17th century can open up so many paths to understanding broader cultural attitudes. Editor: Precisely. It's that interplay between personal emotion and the weight of visual language across the ages that I find so compelling here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.