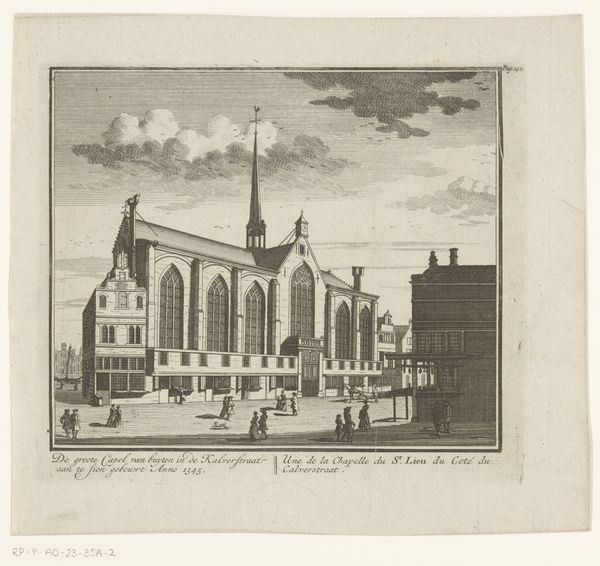

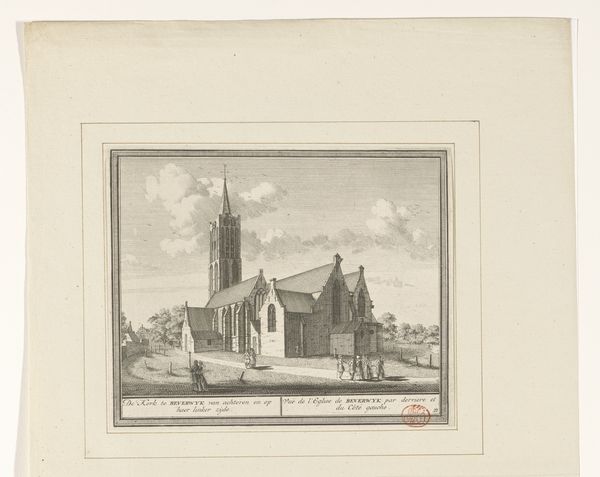

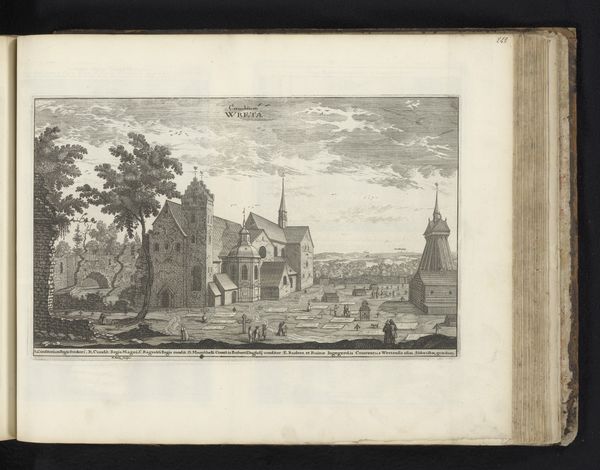

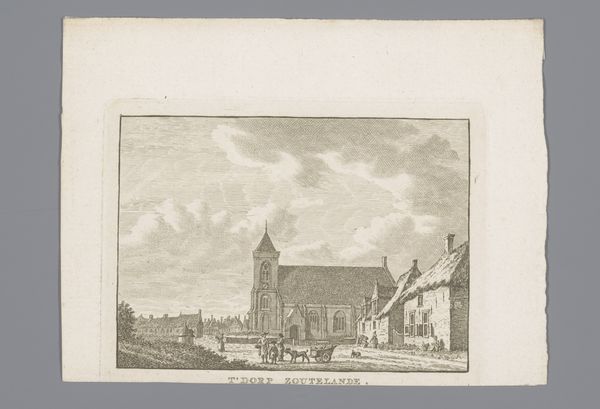

Gezicht op Broek in Waterland, ca. 1790 Possibly 1786 - 1825

0:00

0:00

carelfrederikibendorp

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 157 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

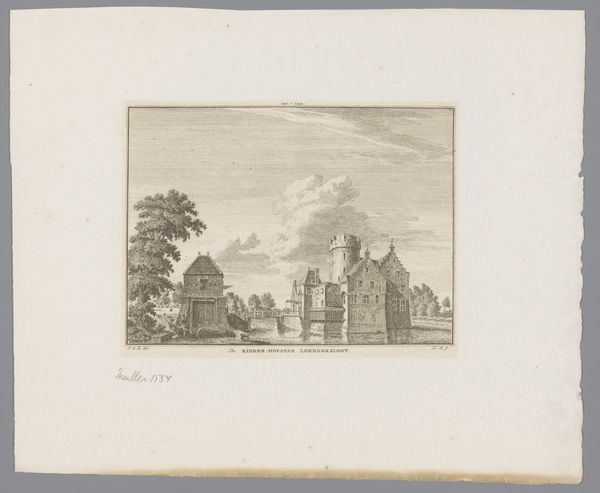

Editor: This is "Gezicht op Broek in Waterland," around 1790, by Carel Frederik Bendorp. It's an engraving, giving the scene a delicate, almost ethereal feel. The village seems so quiet, nestled in the water. How do you interpret this work, given its historical context? Curator: It's a fascinating depiction, especially when we consider the socio-political currents of the late 18th century. What strikes me is the idealized representation of rural life. This wasn't just a neutral landscape; it reflected a desire for order and stability, perhaps in response to the turbulence brewing across Europe. Notice the careful composition and the clean lines of the engraving. It evokes a sense of tranquility but it’s a constructed tranquility. Do you think this constructed imagery speaks to specific class anxieties of the time? Editor: That’s a great point. I hadn’t considered the deliberate "construction" of tranquility. It definitely seems at odds with the pre-revolutionary tension. So the image isn't just a view, it’s also a statement? Curator: Precisely. Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Bendorp and his contemporaries navigated a world of shifting power dynamics and emerging social consciousness. The romanticized serenity can be read as a form of escapism, a retreat into an imagined past, or even as a subtle commentary on the social inequities of the time by presenting an idealized present. Perhaps a desire for something that can’t or doesn’t really exist. Editor: It’s amazing how much deeper the image becomes when we unpack its historical layers! I’ll never look at a landscape the same way. Curator: Exactly! Recognizing art's participation in social narratives transforms our viewing experience entirely. Keep questioning the supposed neutrality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.