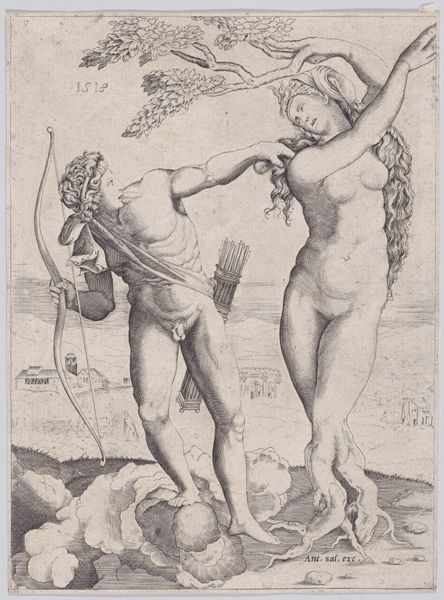

Orpheus standing at left playing the violin, Eurydice at right covering herself 1504 - 1514

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

female-nude

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

#

male-nude

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 15/16 × 5 1/4 in. (17.6 × 13.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

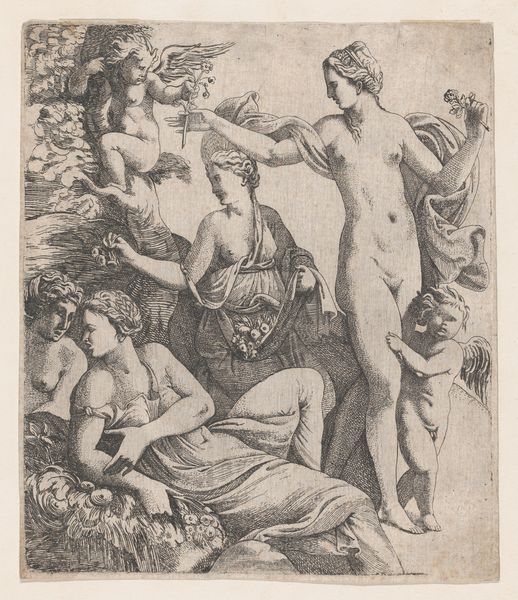

Curator: Standing before us is "Orpheus standing at left playing the violin, Eurydice at right covering herself," an engraving dating back to the early 16th century, somewhere between 1504 and 1514. The artwork is attributed to Marcantonio Raimondi, a prominent figure of the Italian Renaissance, and is part of the collection here at The Met. Editor: Oh, I see immediately that melancholic strain of the Renaissance. It's such a study in muted emotions; both figures seem caught in this quiet drama, an intimate sorrow played out in the delicate lines of the engraving. Curator: Exactly. The piece illustrates the tragic tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, just not the ending that we perhaps yearn for. He’s playing, yet his gaze is downcast, and she averts her eyes, already beginning her return to the underworld. This image really shows Raimondi's skill in translating classical narratives through printmaking, popularizing them for a wider audience. Editor: He almost traps them both in amber! But, there's a palpable tension here; the violin—a strangely anachronistic touch, isn't it, for the Orpheus myth—seems almost like a barrier, physically and emotionally, separating them, rather than the means to their reunion. Is Raimondi commenting on art's limitations, perhaps? Its inability to fully bridge life and death? Curator: It's certainly a point of discussion, the violin, with its elaborate form depicted. Raimondi likely borrows the figures' idealized forms from classical sculpture and combines them with contemporary musical instruments. The musical aspect of Orpheus’ myth had particular social currency then, particularly associated with artistic gatherings. It reflects not just a retelling, but a re-envisioning of a classical story through the lens of the Renaissance, a bit like remixing an ancient song with modern instruments, if you will. Editor: It does make you think about art’s constant renegotiation with the past. You've got this intensely private moment, made public through reproduction, now framed and preserved for us. How do we wrestle with these inherited images of grief, love, loss, that just circulate endlessly in museums, in popular consciousness, each time accruing more meanings, and peeling away more history? Curator: That’s very eloquently put. This work showcases the beautiful tension of influence, borrowing, and reinvention that sits at the heart of the Renaissance itself. Editor: So in its muted grief, perhaps this engraving whispers about our own fragile acts of preservation and interpretation, forever in conversation with those long gone?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.