engraving

#

baroque

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

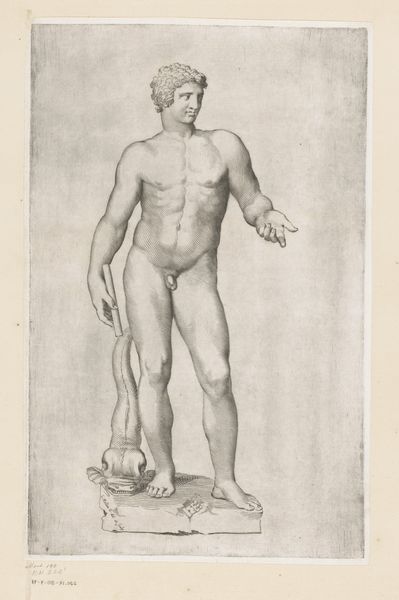

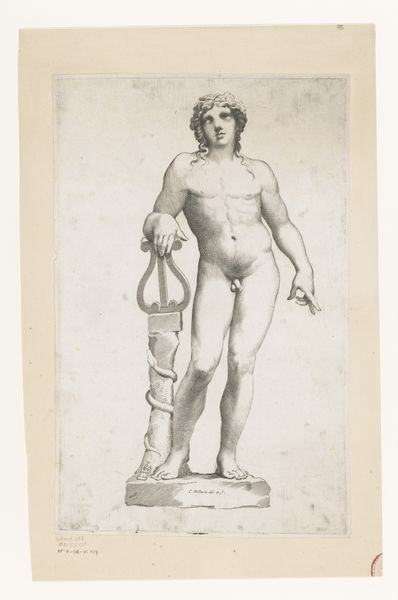

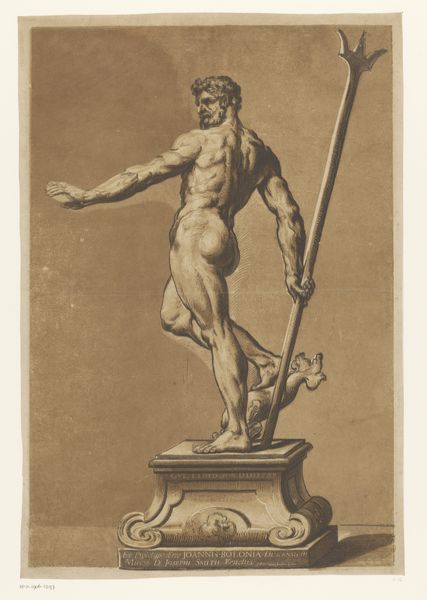

Dimensions: height 371 mm, width 237 mm

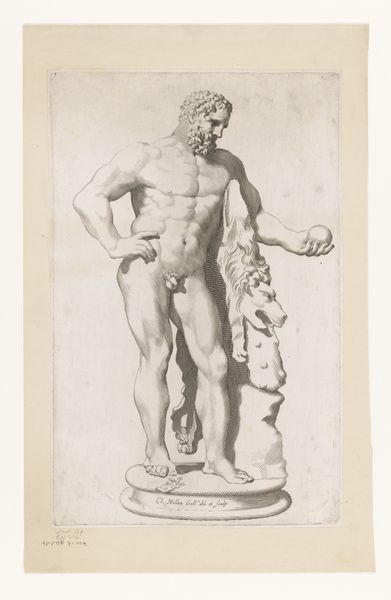

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at "Standbeeld van Apollo" by Claude Mellan, created sometime between 1631 and 1637. It’s an engraving at the Rijksmuseum. There’s something so classical and clean about it. The stark lines create this sense of serenity despite the, ahem, nudity. What do you make of it? Curator: Serenity, yes, precisely! There's an almost clinical coolness to Mellan's Apollo. Have you ever felt the cool marble on your fingertips while wandering through ancient ruins? That’s what this evokes. But also, consider Mellan's technique. He wasn't just copying a statue, he was translating a three-dimensional object into a series of exquisitely controlled lines. What do you think that act of translation does to the image? Editor: It almost...idealizes it, right? Like stripping away the flaws and getting to the essence. Makes him seem even more godlike. Curator: Precisely! Think about the context. The Baroque period was obsessed with dynamism and emotion. Mellan's almost sterile approach is a fascinating counterpoint. It's like he's saying, "Here is perfection, untouched by human drama." Almost rebellious, wouldn’t you say? Editor: Absolutely, I never thought of it that way, but it definitely sets him apart. The almost scientific precision feels really modern somehow. Curator: Doesn’t it? Art is full of delightful contradictions like that. What began as a revisiting of classicism transformed into something entirely its own. And I think the medium contributes too. There’s a severity to engravings, a sense of stark precision… which seems like an idea worth holding on to, or exploring in one’s own way. Editor: I see it too! So, looking at it from this angle, what seemed classical and reserved is really quite revolutionary! Curator: Exactly! And that’s why it keeps whispering to us across centuries. It reminds us there’s always more to the story, waiting to be unveiled.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.