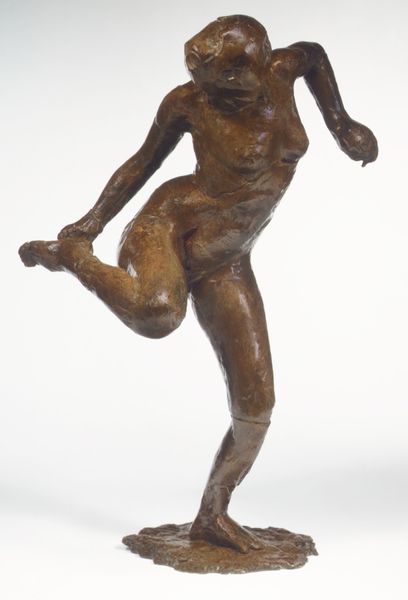

Dimensions: Overall: 12 1/4 × 9 3/8 × 5 9/16 in. (31.1 × 23.8 × 14.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Edgar Degas's "Dancer in the Role of Harlequin," likely conceived between 1879 and 1920. It's a bronze sculpture currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It looks like she is bracing herself before a big leap or even just a huge pratfall. Like right before she’s about to do something incredibly mischievous! There is definitely tension in that pose. Curator: Indeed, there's a certain precocity evident in the tilt of her head and stance. However, placing this work within its social context is crucial. In Degas’ time, ballet was a heavily policed and exploitative industry, especially for young female dancers. It was by no means a field dominated by privileged and wealthy children. Editor: It’s a rough rendering of a dancer for sure! Not romantic in the least. Sort of angular, rough texture, even... Is she actually *nude* as well? What about the harlequin getup? Curator: That’s right. Though we are talking about an artist celebrated for capturing ballerinas en pointe, we should remember that, at its base, Degas’ oeuvre depicts labour. This piece portrays a dancer in a state of near-nudity, likely during a break in the studio, capturing the harsh reality beneath the veneer of the theatre. We should remember that her lack of adornment renders her both physically vulnerable and socially exposed. The reference to Harlequin does however also serve a symbolic function by associating her with both theatrical performance and personal anonymity. Editor: Gosh, that takes away a bit of the playful feel, then. It feels weighted with... otherness. Almost sinister in a way to know she may be trapped and working, not skipping along living an enchanted life. I do also wonder why he never finished the costume and how that affects this dynamic we’re talking about. Curator: Well, it pushes to the foreground ideas of artistic creation, and in turn, this complicated nexus of bodies, identity, and work in 19th-century Paris. The rawness certainly contributes to the sense of labour rather than spectacle, doesn’t it? Editor: Definitely changes everything. So I think from now on I will probably bring both understandings with me when I revisit it—both the possibility of performance, but also awareness and appreciation of what that entails. Curator: A rewarding tension, indeed. I agree it reframes how we think about these very loaded historical artworks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.