Copyright: Public domain

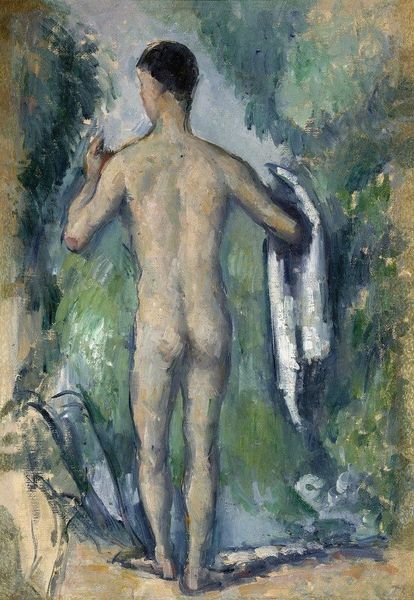

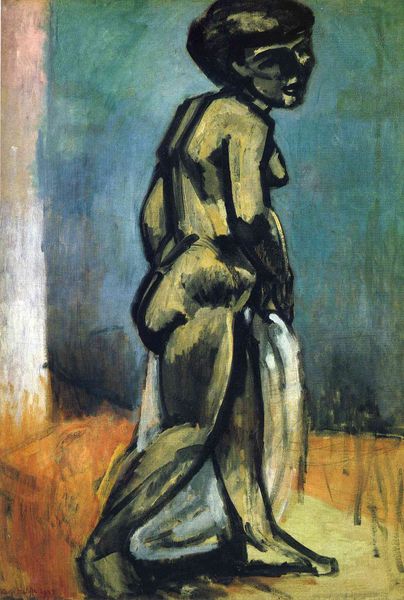

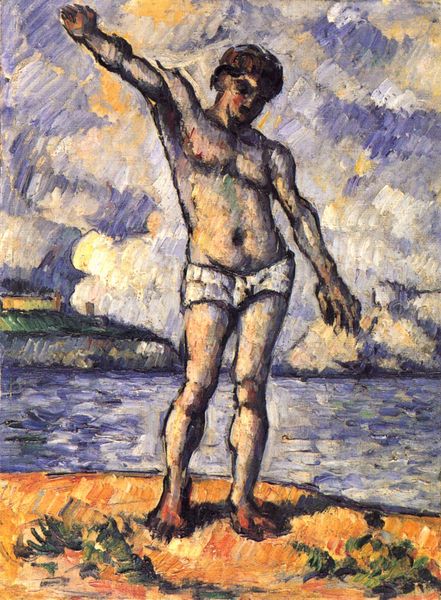

Curator: Let’s take a moment to consider Paul Cézanne’s “Bather,” created around 1877. Editor: My immediate impression is one of intriguing ambiguity. The figure seems both monumental and vulnerable, emerging almost organically from the swirling landscape. Curator: It’s compelling to consider the positioning of the nude male figure within a landscape traditionally associated with the female gaze. Cézanne, by presenting a male nude, subverts the expected power dynamic, opening a dialogue around representations of masculinity in art. The gaze and who controls it, takes central stage in understanding modern art. Editor: I am struck by how the planes of color define the figure. See how those confident, almost geometric brushstrokes model the musculature. It's an attempt to represent form not just as perceived, but conceptually understood through geometry, don't you think? Curator: Yes, and it goes further; look at the seemingly incomplete rendering, almost as if dissolving back into the surroundings. The “unfinished” quality may allude to broader ideas of fragmented and unstable male identity during rapid modernization in late 19th century Europe. How can we really perceive an identity as solid or monolithic given such social changes? Editor: I agree to an extent, although that may be a function of Cèzanne's working style as well, of his particular theory about vision. To that point, notice how he juxtaposes strokes of green, yellow and blue to construct the figure. Curator: That fragmentation also aligns with feminist and queer theories that deconstruct the male "gaze" by displaying it as something always changing, under construction, and open to reinterpretation. He is challenging the traditional phallocentric power of visuality by disassembling how we even “see” or “understand” it. Editor: What I appreciate is Cézanne's relentless interrogation of form and the way color can delineate volume. The subversion of expectations is almost entirely formal, though the points about gender are useful to highlight historical interpretations. Curator: Precisely, the power resides in the layered readings—Cézanne encourages questioning norms through both his form and what it might mean historically. It shows how the gaze isn’t stable but always constructed through painting, class, gender, and so many other lenses. Editor: This reminds me to re-evaluate my own initial formal impressions about it every time, such as noticing how Cézanne challenges our preconceived notions about color and representation itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.