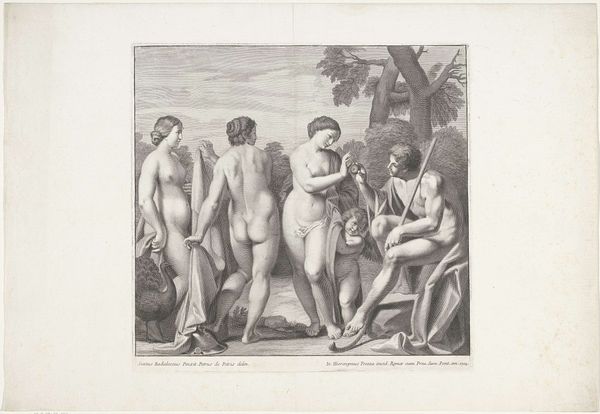

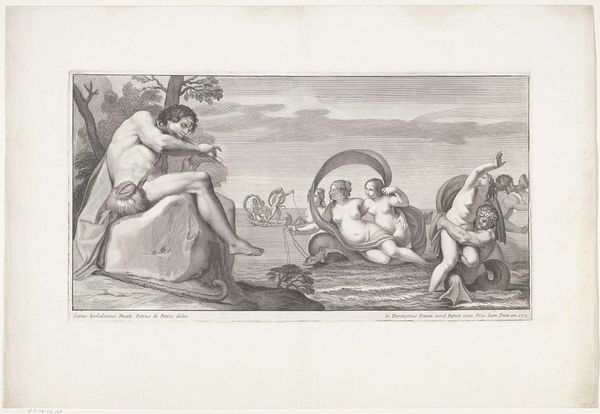

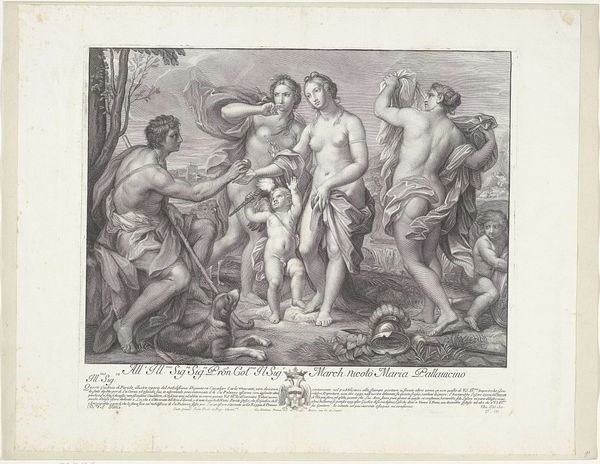

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 350 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Diana en Actaeon", an engraving created around 1713 by Giovanni Girolamo Frezza. It depicts a scene from classical mythology. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Well, right away, the crisp lines and the stark contrast grab me. It feels… theatrical, almost staged. The way the figures are arranged, there is an overt contrast to that background's light rendering that lends the foregrounded subject-matter, mostly people, an uncanny realness. I think it lends that same effect into that very hunter, Actaeon. Curator: It does feel quite staged, doesn't it? The narrative here is Ovid’s tale of Actaeon, who stumbles upon Diana and her nymphs bathing. As punishment for his intrusion, Diana transforms him into a stag, and he is then hunted down by his own hounds. Editor: Transformation as consequence... that’s heavy material. Look at how Frezza renders Actaeon, with his body already mid-change, caught between man and animal. It’s all labor; from the ink preparation to the detail the artist makes on his skin. Curator: Absolutely. And think about the societal context in which this print was created. Frezza was working in a period where such mythological scenes were vehicles for exploring moral lessons. There is a discussion about transgression and divine retribution. But even beyond moralizing, how do these images function within print culture itself? Editor: That’s the thing, this print isn't just *of* labor; it *is* labor. Each line painstakingly carved. Think about who could access such a thing back then and what kind of consumer would purchase such an image for the home. Plus, its existence proves the network involved: from the artist's hand to the publisher and vendors distributing and profiting. What political purpose might those scenes of violence imply in public places? Curator: Exactly! These prints circulated widely, reaching audiences beyond the elite. This work becomes embedded within the culture and socio-political consciousnesses that extend beyond just what that particular artist has to say about it, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Agreed, in understanding its full breadth and reach, and knowing who touched the artwork helps connect our understanding of production, to display, to even how the image circulates in public view. It becomes less precious that way and all the more part of history as a whole. Curator: Indeed, that exploration of production helps in unraveling complex readings of our relationship with such narratives. It certainly puts a lot of depth into what this particular image represents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.