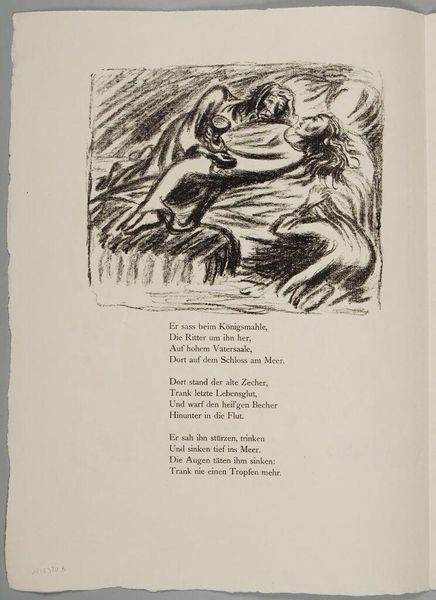

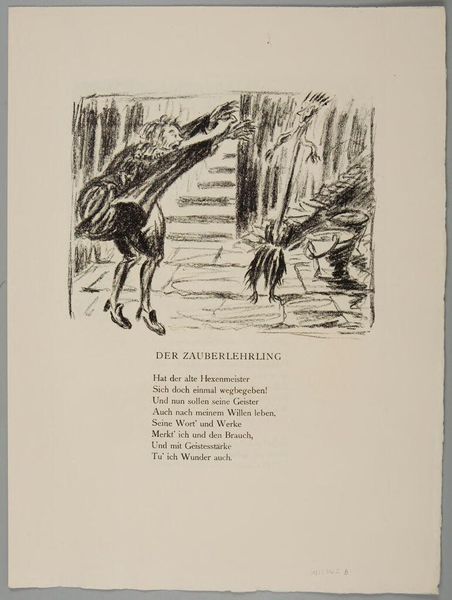

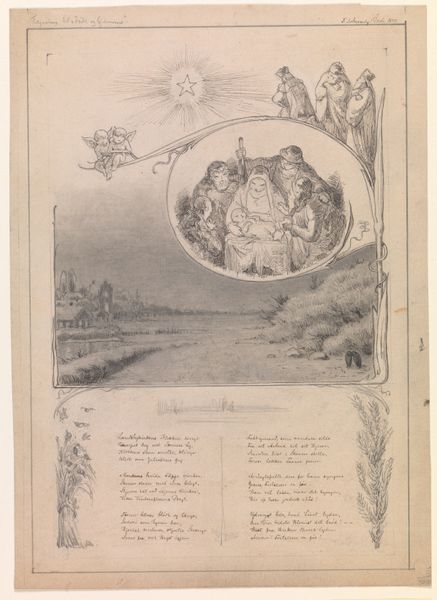

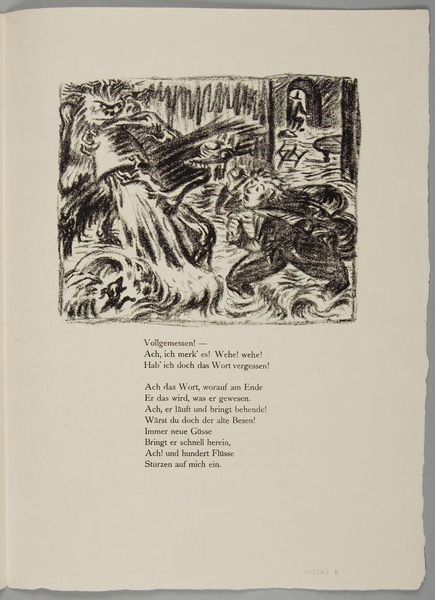

Die neue Sommerzeit (The New Summertime) (recto) and The Ride (Die Fahrt) (verso) 1916

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphic-art, lithograph, print, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

Dimensions: 13 7/8 × 10 13/16 in. (35.24 × 27.46 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

Curator: This lithograph by August Gaul, created in 1916, is titled "Die neue Sommerzeit," or "The New Summertime." On the reverse is another work titled “The Ride.” Editor: My first impression is of unsettling nostalgia, like a child's storybook haunted by darker implications. There's a deliberate crudeness in the linework that seems to clash with the quaint imagery. Curator: The piece exemplifies how Gaul explored themes of rural life and the changing relationship with nature, particularly as industrialization accelerated. The deliberate choice of lithography allows for a mass production, placing art into a social context outside traditional spaces. Editor: The rooster, the hens, even the corn stalks... They seem imbued with symbolic weight beyond their simple representational function. Look at how the clock dominates the composition. Doesn't it feel less like a charming scene and more like an allegorical judgment? The German text reinforces this—it is not merely descriptive; it is commentary. Curator: Consider the sociopolitical climate of 1916, deeply embedded in war. While Gaul did primarily work with bronze, prints such as this one made the work accessible in ways bronze sculpture wasn’t and at this moment in time, more people would likely connect to the theme. Editor: And look at the way the animals interact with the clock. They are oblivious, unaware of time’s relentless march, a possible symbol for humanity itself during wartime or on the brink of momentous change. Curator: Right, and that juxtaposition serves to critique industrial acceleration as if it ignores organic life cycles in nature itself. The material fragility of the paper contrasts sharply with the industrial age's seemingly indestructible ethos. Editor: I appreciate your reading. The overall impression is more multifaceted than just a rustic scene. I am left reflecting on time and nature under human influence and the unsettling ways our world reflects them back at us. Curator: Agreed. It prompts us to reconsider the narratives we construct around time and our relationship with the land. The accessibility of print media here brings awareness of such issues into broader consciousness, challenging our aesthetic expectations.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart almost 2 years ago

⋮

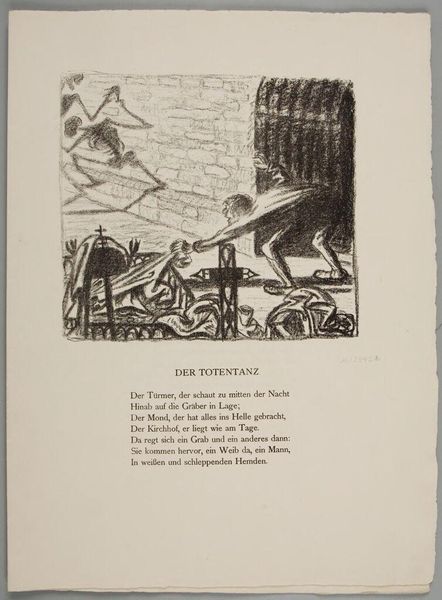

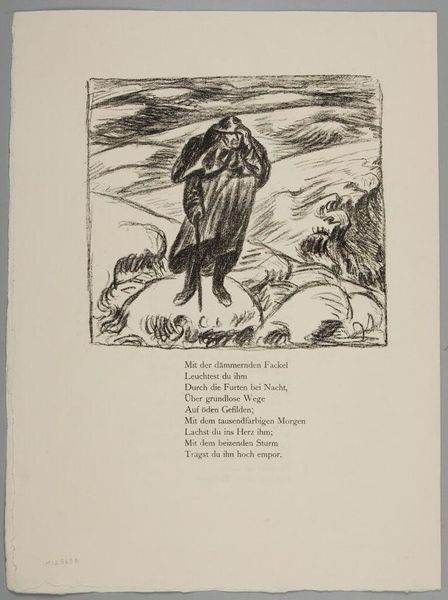

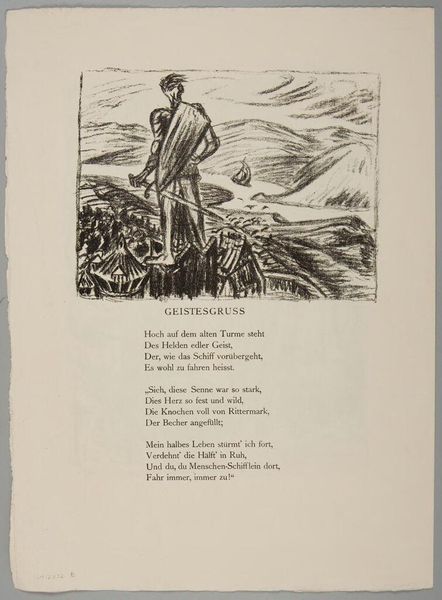

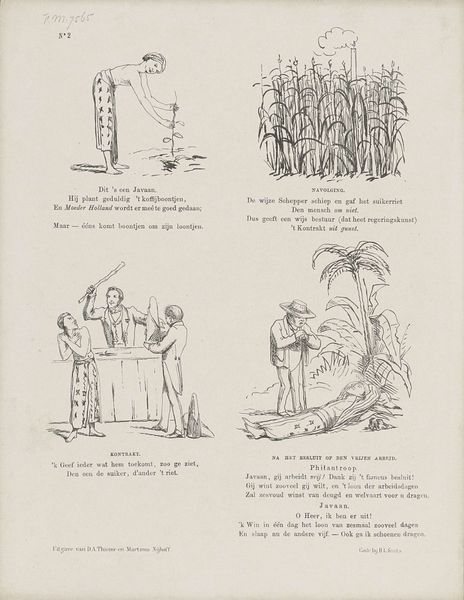

In 1916, publisher Paul Cassirer started a new periodical, "Der Bildermann" [The Picture Man], "to bring a broad public directly in touch with art." It featured original lithographs that sought to offer beauty as a form of relief from the grinding brutality of World War I. Leo Kestenberg, a pianist and pacifist, ran the journal while Cassirer served in the army. Max Slevogt designed the vignette on the masthead, which shows a man peddling broadsheets to eager soldiers and civilians of all ages and stations. "Der Bildermann" embraced the art of impressionists (such as Max Slevogt), expressionists (Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner), and naturalists (August Gaul). Dwindling subscriptions, increasing difficulties with censors and the bureaucracy, led to "Der Bildermann’s" demise after only eighteen issues.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.