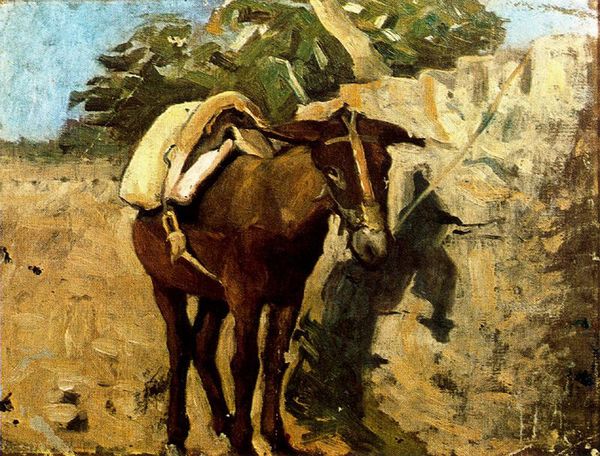

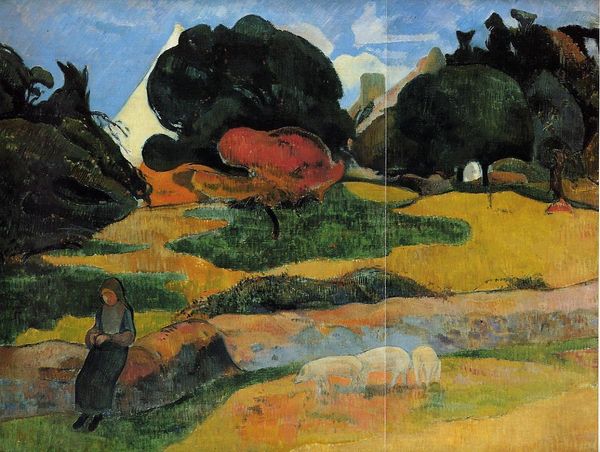

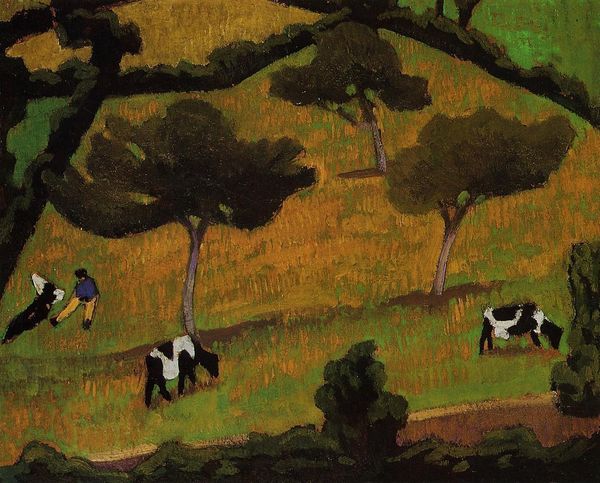

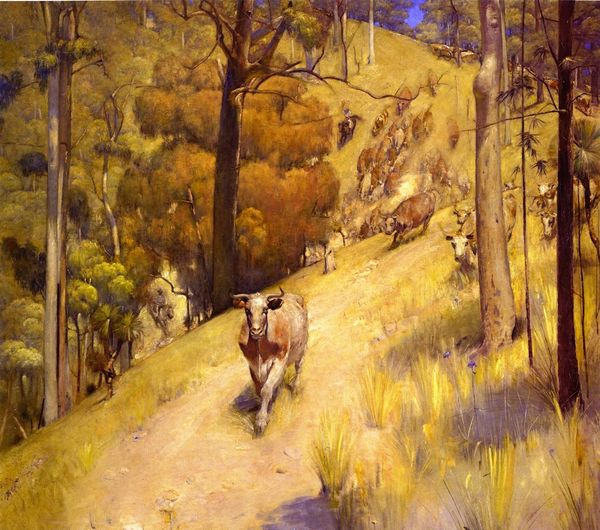

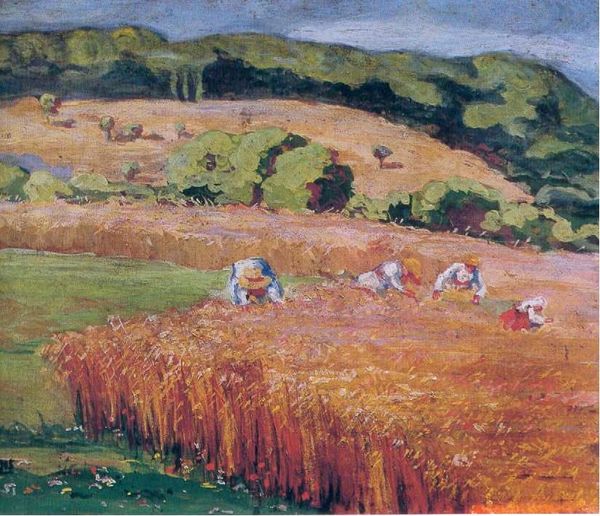

painting, plein-air, oil-paint

#

painting

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

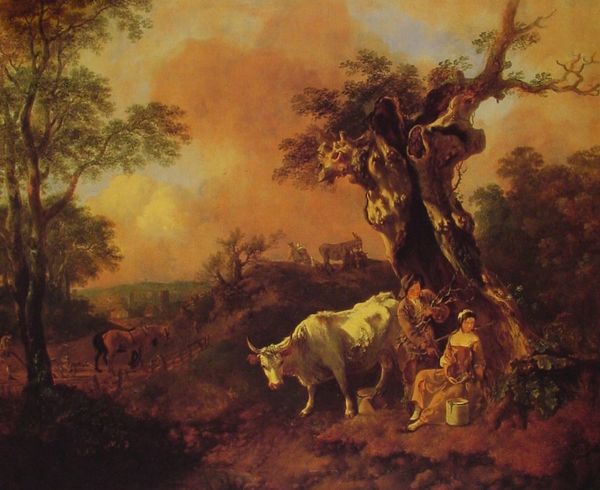

landscape

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

genre-painting

#

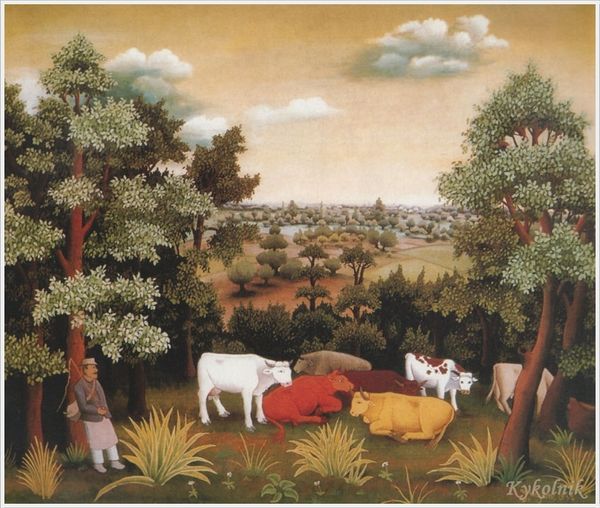

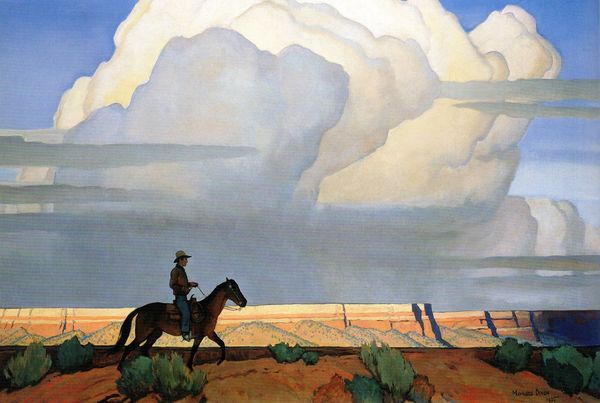

regionalism

#

realism

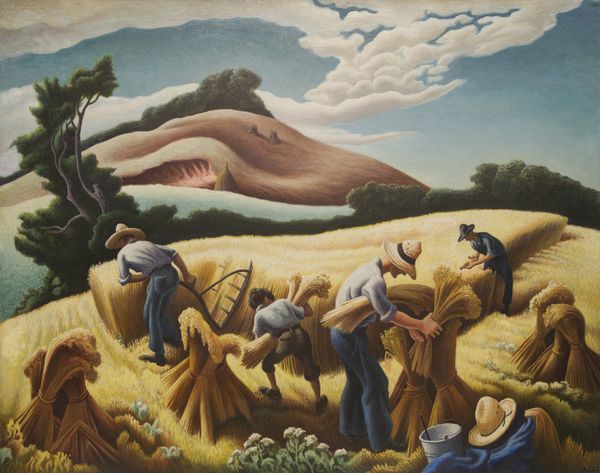

Copyright: Thomas Hart Benton,Fair Use

Editor: This is Thomas Hart Benton’s “July Hay,” painted in 1942, now at the Met. The warmth of the golden hayfield contrasts with the darker, cooler foreground, creating this inviting yet somewhat uneasy feeling. What stands out to you? Curator: I see a very deliberate construction of American identity occurring against the backdrop of a nation at war. Benton's regionalism wasn't just about depicting a place; it was about building a visual mythology. Look at the two figures toiling in the fields. How do you think this idealized representation relates to the social realities of rural America during that era? Editor: I guess it's almost romanticized? It’s like he's celebrating this rural lifestyle at a time when it might have been fading. Curator: Precisely. And who is this imagery intended to resonate with? Think about the urban audiences, museum-goers… How does this romantic vision play into wartime anxieties and the need for a unified national narrative? Benton received several public commissions, didn’t he? This one wasn’t public-funded. Editor: Yes, but seeing the work in a museum, so separated from the reality of farm work… I wonder if the message still resonates, or if it becomes more about pure aesthetic appreciation now. Curator: That's the tension inherent in art’s relationship to power and how museums participate in constructing our understanding of culture. Do you find any indication of class, social stature or race represented here? Editor: Not explicitly. It’s a very homogenous vision, I’d say. Curator: Precisely, it’s carefully designed. Editor: So, looking beyond the surface beauty, it’s really about understanding what this image says about America in the 1940s and who got to be part of that story. Curator: Absolutely. And that’s where art becomes a powerful tool for understanding our shared past. We shouldn't just look; we need to critically examine.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.