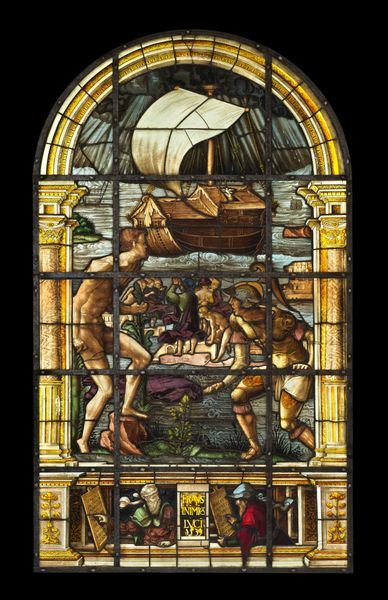

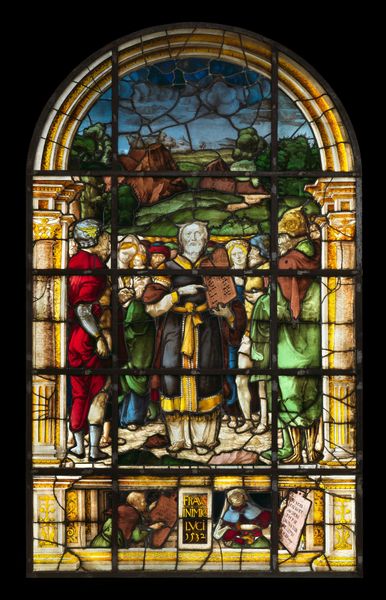

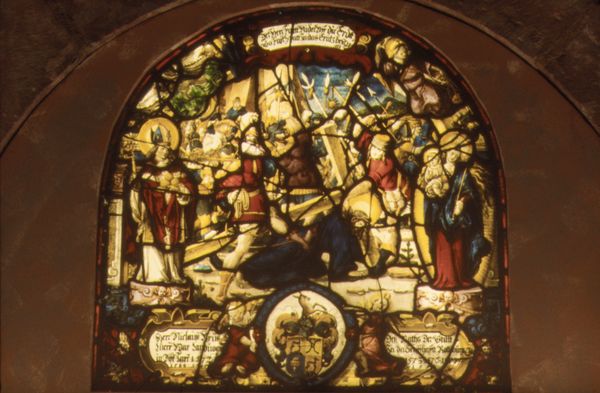

Ruit met voorstelling van Mozes op de berg Sinaï c. 1525 - 1550

0:00

0:00

pietercoeckevanaelst

Rijksmuseum

glass

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

figuration

#

glass

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 68.5 cm, width 48.0 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this stained glass panel depicting Moses on Mount Sinai, what strikes you first? Editor: The stark contrasts! The bright robes against the shadowy figures, the opaque density versus the translucence... it really emphasizes the divine spectacle unfolding. I can almost feel the weight of those glass sections and wonder at the craftsmanship that formed them together to make the image. Curator: That’s perceptive. This panel, titled “Ruit met voorstelling van Mozes op de berg Sinaï,” comes to us from around 1525-1550, attributed to Pieter Coecke van Aelst. It illustrates the pivotal moment when Moses receives the tablets of the law from God, surrounded by the Israelites waiting below. Consider its role not only as an artistic creation but a vehicle for biblical narrative, informing the populace through visual means. Editor: Precisely, and the material inherently directs that narrative. Stained glass, by its nature, involves collaboration—artisans preparing the glass, others painting the details, and someone leading the assembly. This means a layering of intent and skill and process, embedding community stories and labour directly into the work, it's pretty hard to ignore. I bet that different colours came from different shops each specializing in that material outcome. Curator: Yes! Moreover, placing it in a larger framework: religious iconography, particularly in the Northern Renaissance, had distinct sociopolitical implications. These stained glass works frequently appeared in churches or affluent private residences. The very act of viewing such a piece had its class-based politics, mediating power. The museum setting itself further mediates those factors of the object. Editor: The intense detail is undeniable when seen up close. I can appreciate the fine details—the faces looking up, the texture achieved through the pigments—the way light could flood in from behind is what really completes this and makes you experience it as it should be, especially from the original intended viewing experience from around the 16th century. What about the composition calls out to you? Curator: For me, it’s how the figures almost emerge from the landscape. This elevates Moses' story, the chosen leader on a divine stage set. Each time one views such a panel, they actively consume and reshape that relationship of authority, albeit filtered by museum structures today. Editor: It truly makes you think about not just the divine law being handed down, but also how images themselves get made and handed down across centuries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.