Copyright: Public domain US

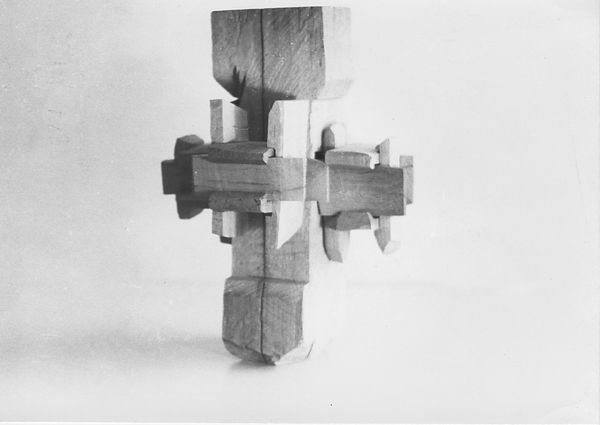

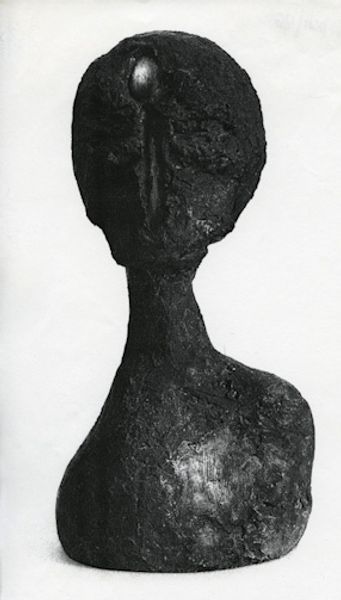

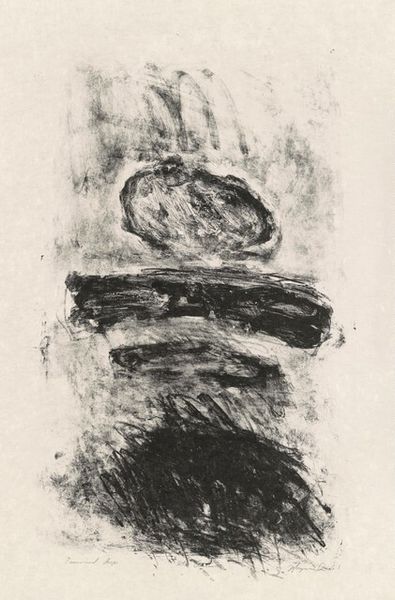

Editor: This is Constantin Brâncuși's "The First Cry," made in 1917. It’s a sculpture made of wood and presented in a black and white photograph. It has an unsettling yet primal energy about it. How do you interpret this work, especially considering its historical context? Curator: That primal energy you sensed is key. In 1917, during the throes of World War I, Brâncuși crafted this totemic form. Can you see how it embodies the violence and upheaval of the era? Its starkness speaks volumes. Editor: Absolutely, it's impossible to ignore the connection. The rough texture of the wood, combined with its abstract shape, evokes a feeling of vulnerability and rawness, almost like exposed bones. How does the title “The First Cry” fit into this interpretation? Curator: Precisely! It signals a beginning, a birth, but also perhaps a primal scream in the face of existential horror. Consider the avant-garde movements of the time: Dadaism, Surrealism...all grappling with trauma and a world shattered by conflict. Do you think the simplification of form here, stripping away representational details, is a deliberate act? Editor: It feels like a rejection of traditional artistic conventions. To me, the reduction to such basic forms emphasizes a return to fundamental human experiences, like pain and fear, shared universally regardless of background. Curator: Exactly. And consider how Brâncuși, through the manipulation of material, offers a voice to something pre-verbal, pre-rational. "The First Cry" is not just an individual's cry but also the collective cry of a generation confronting modernity's devastation. How do we, as contemporary viewers, confront this cry today? Editor: Perhaps by acknowledging the enduring relevance of art that speaks to shared human experiences of suffering and resilience. It’s a potent reminder of our collective responsibility in the face of contemporary crises. Curator: A crucial point. Art like this insists we confront our own complicity in systems that perpetuate suffering, demanding that we engage with history not as a detached observer, but as active participants shaping a more just future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.