print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 199 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

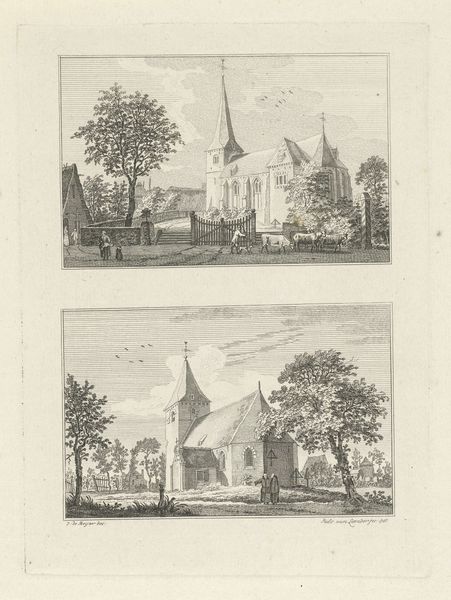

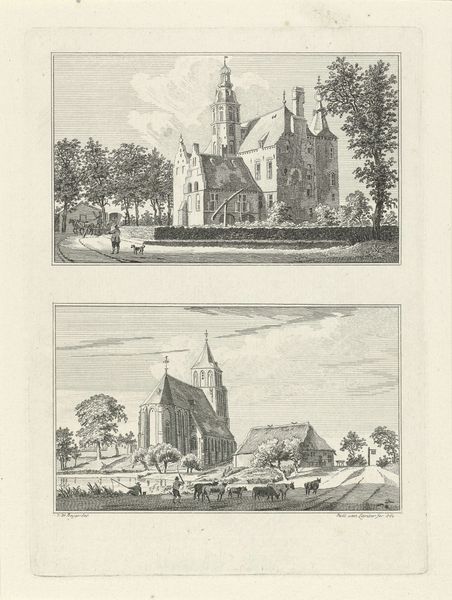

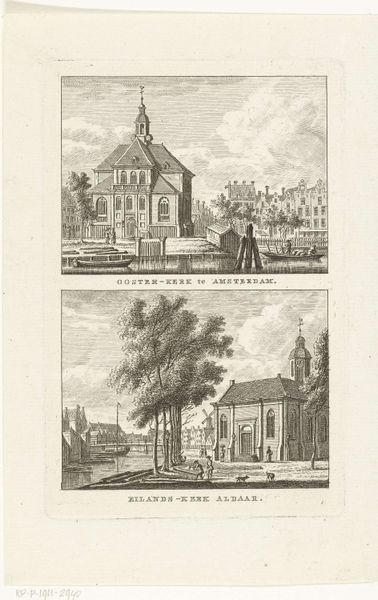

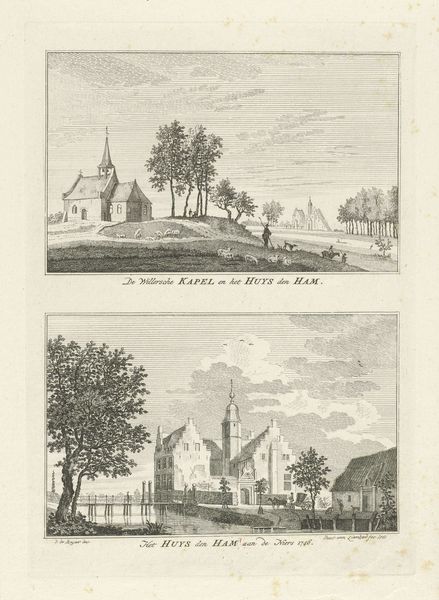

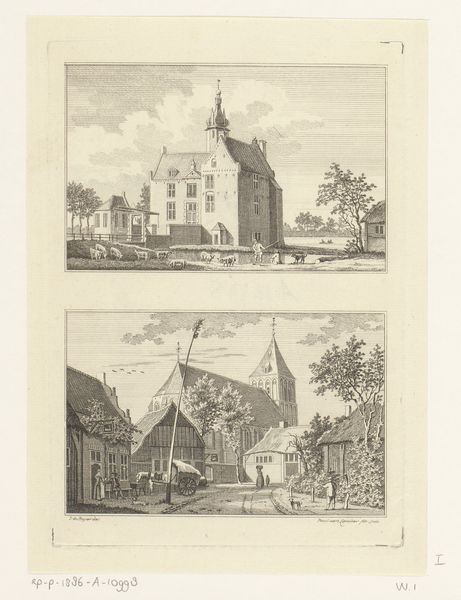

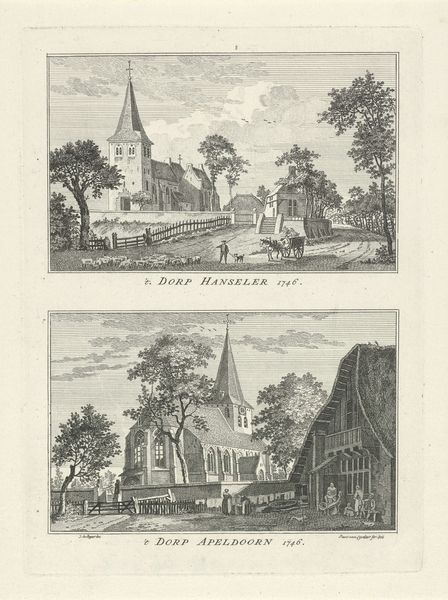

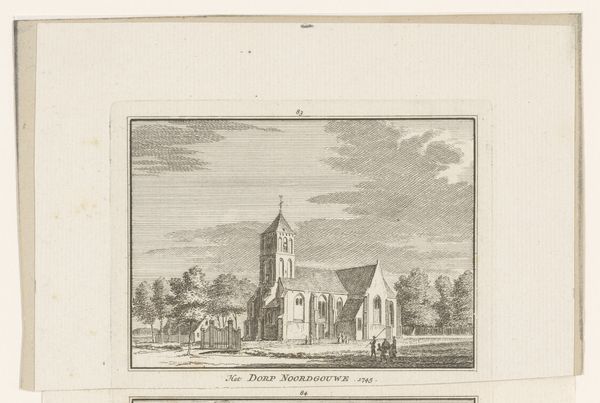

Curator: Well, hello there. This engraving by Paulus van Liender, titled "Dorpsgezichten te Hassum en Hommersum, 1746," but actually made around 1760, gives us two quaint Dutch village scenes in one composition. What catches your eye first? Editor: It's… charmingly mundane, I suppose. The detail in the buildings is appealing but also gives it the vibe of a carefully cataloged inventory. There’s something quite neutral in the feel, despite the clear skill involved. Curator: Yes, the meticulous details do invite closer examination. Van Liender’s work is fascinating in how it elevates the everyday. We must remember that this print circulated within specific networks of patronage and print shops. The rise of the print market and the networks between artists and publishers allowed for new methods of distributing information, especially visual information about places near and far. Editor: That’s right, it wasn't just artistic expression. Prints were commodities produced by labor. Engravings required training, specific tools, and the involvement of printers. We must think about this circulation as a cultural process as much as an aesthetic experience. So who consumed these images and for what purpose? Curator: Likely affluent landowners, or members of the rising middle class. These images served to document their property holdings and maybe even project an idealized vision of their domain and way of life. There’s a strong sense of order, but a sanitized one too, if you look closely. Where is the dirt, noise, and physical work involved in making this community run? Editor: It also reminds me that printmaking offered a different class of artists new opportunity: It democratized art in some ways, and yet its own techniques reproduced hierarchical access to visual culture. The ability to copy and reproduce something becomes important in how we consume information in public. Curator: Absolutely. And while these images portray rural life, we cannot see it separate from the booming urban centers that consumed prints en masse. The rise of Amsterdam and other major cities gave way to print workshops that made work for all different audiences. The art itself became something of an artifact. Editor: Exactly. Thinking about the networks between artists, printers, merchants and the broader social context reframes our interpretation. What seemed at first merely quaint landscape becomes loaded with socio-economic weight. Thanks for guiding us through this work and considering it within these crucial systems. Curator: Of course, analyzing the history and the processes really underscores the artist’s choices and the ultimate influence this work had on society during the Dutch Golden Age.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.