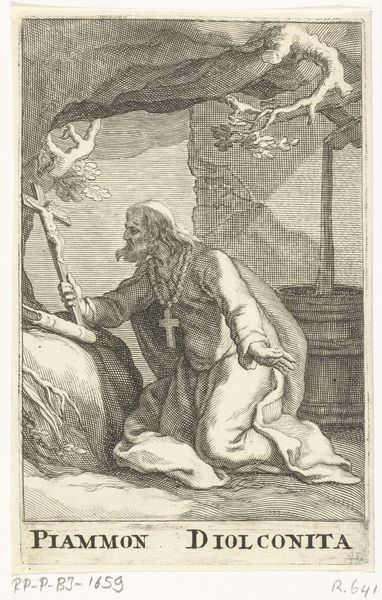

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is "Heilige Anuph," created by Frederick Bloemaert sometime after 1636. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum's collection, and crafted as an engraving on paper. Editor: It’s striking! The contrast of light and shadow is quite dramatic, especially on the figure's robes. It also looks so austere with a rather desolate feel. Curator: Austere is an excellent observation. The subject, Saint Anuph, gazes upward at a divine vision in the heavens while standing in a seemingly barren landscape. But what can we read into that contrast? What relationship to the materiality or context of making can you deduce? Editor: Given the period, engravings such as this one served as both devotional aids and means of disseminating imagery widely. This was, I suspect, produced not necessarily as fine art but as part of a larger industry responding to, or even fueling, particular religious or political sensitivities. Curator: Exactly! Bloemaert, or someone working under him, skillfully employed engraving to produce a kind of reproducible icon for a populace perhaps craving spiritual guidance during tumultuous times. Notice also the level of craft involved in creating such fine lines. How do you think the figure conveys the relationship with those labor intensive processes, and moreover with his own material, earthly constraints? Editor: It reminds us about penance and austerity. Consider the landscape - its function within society in early modern landscape imagery of the baroque era. It's a stark contrast, and the saint's gaunt appearance further underscores the sacrifice and denial associated with sainthood. Also I have to admit that his facial hair could use a little care. Curator: It's a great point about earthly constrains that is underscored also with bare feet. How do you think Bloemaert, via this visual economy, engages questions of spiritual labor versus earthly toil for early viewers of his printed picture? Editor: Ultimately, it’s a piece reflecting its socio-political and religious milieu, designed to evoke contemplation and reinforce specific ideologies within the emerging Dutch Republic's evolving public sphere. And even with bare feet in those circumstances, his place of honor remained above earth and toil. Curator: Agreed. It’s remarkable how this one small print speaks to those ongoing negotiations, giving us a window into the material conditions of faith and its dissemination through artmaking of the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.