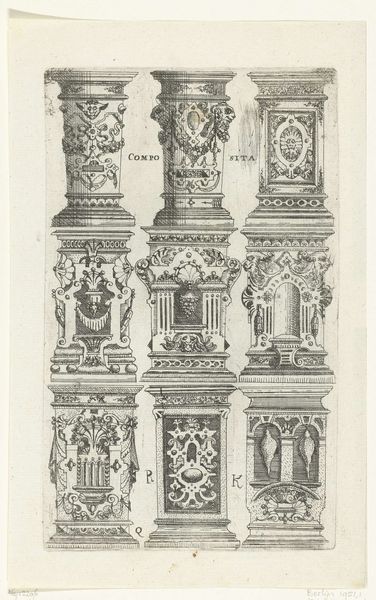

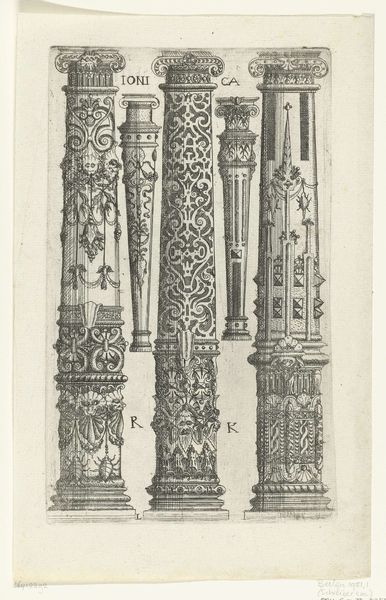

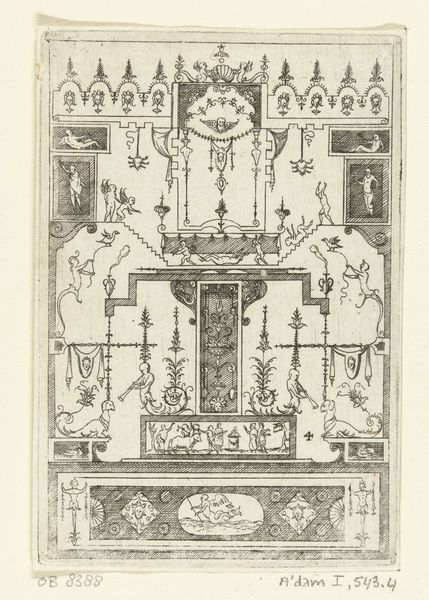

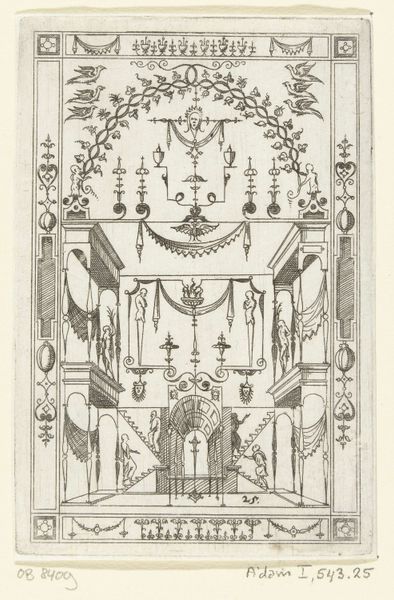

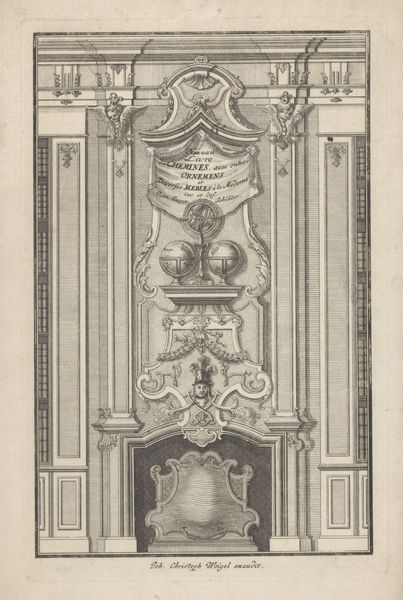

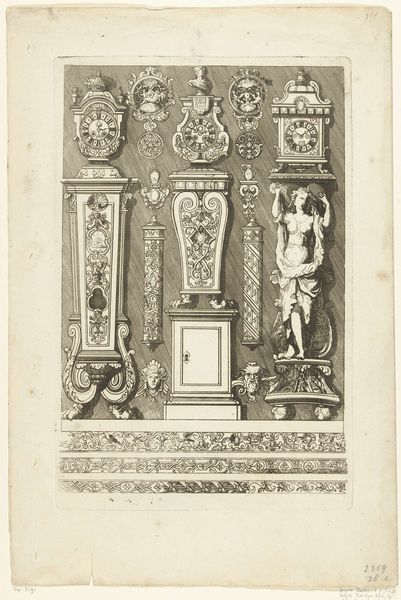

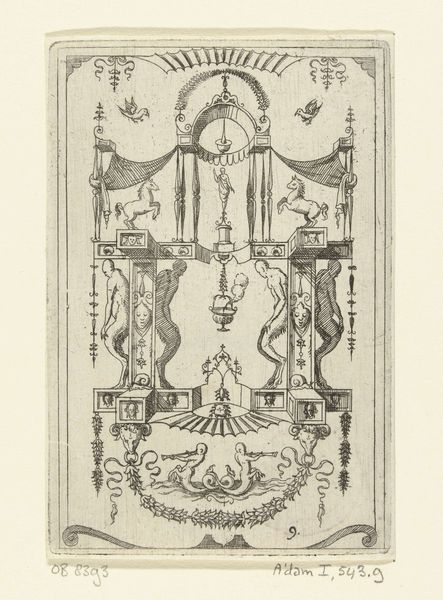

Dimensions: height 279 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Drie comtoise klokken en dertien kleinere motieven," a pre-1800 engraving now housed in the Rijksmuseum, created by an anonymous artist. I find the level of detail captivating, like peering into a watchmaker’s meticulously organized workshop. What story do you think this work is telling us? Curator: Well, considering the historical context, it speaks volumes about the rise of the bourgeoisie and their relationship with time. Before standardized time, communities relied on natural cues. Clocks, especially ornate ones like these, became status symbols. Editor: So, owning a clock wasn’t just practical; it was a way of displaying wealth and power? Curator: Precisely. Look at the baroque detailing – the flourishes, the engravings. These weren’t mass-produced items; they were crafted, each reflecting the owner’s status and the artistry of the maker. This print then circulates the designs, making them more widely accessible, at least visually. What does that suggest to you? Editor: It's a way of democratizing design ideas, right? Even if you couldn't afford a clock like this, you could still appreciate the aesthetic, or maybe aspire to own one someday. It's interesting how prints played a role in spreading artistic and technological knowledge. Curator: Exactly. Think about the public role of prints at the time, how they influenced taste and desire. And also consider the power dynamic – who had access to these images, and what messages were being subtly conveyed about social hierarchies. Editor: I never thought about clocks in terms of power and social standing before. Curator: That’s the beauty of art history – it’s not just about aesthetics, it’s about understanding the forces that shape our world and how even something as seemingly mundane as a clock becomes embedded in a web of cultural meanings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.