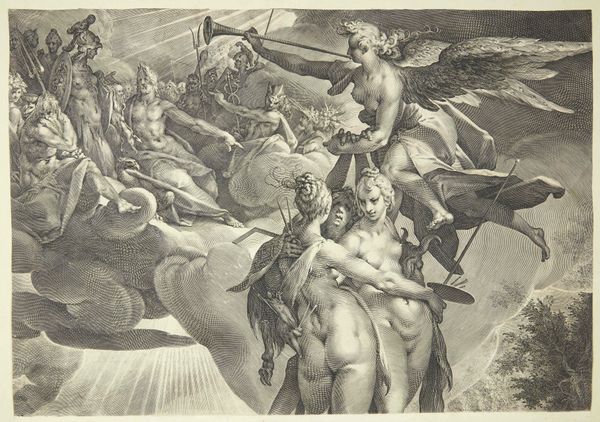

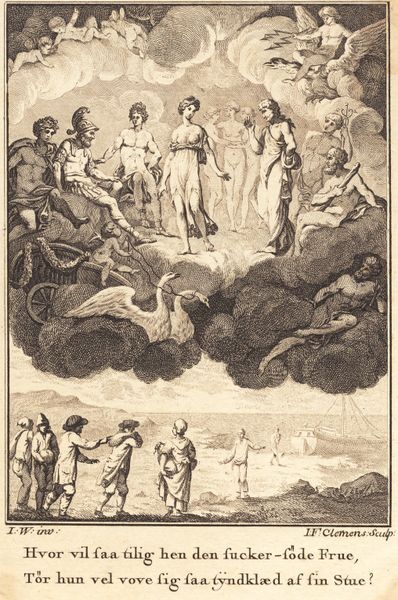

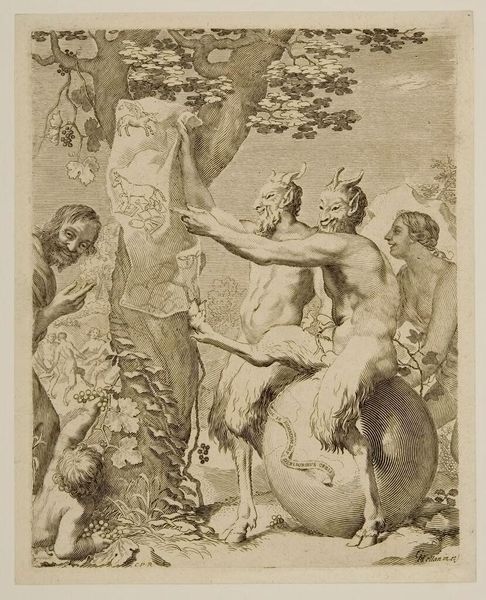

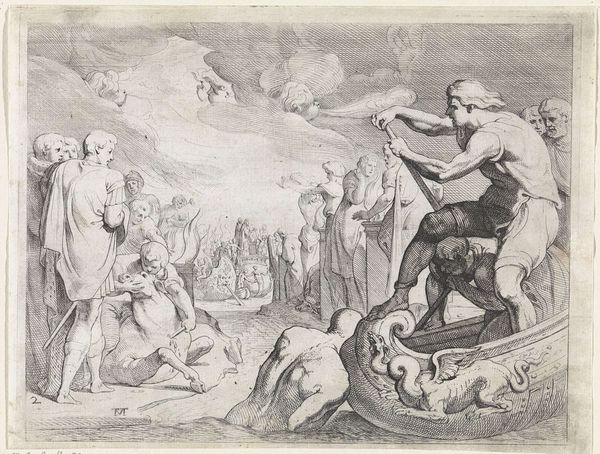

painting, oil-paint

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 33.5 cm, width 189.0 cm, height 42 cm, width 220.4 cm, depth 11 cm, height 50 cm, width 230 cm, depth 10 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

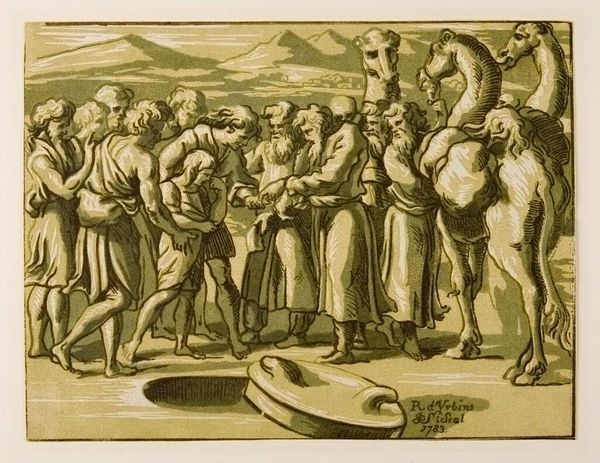

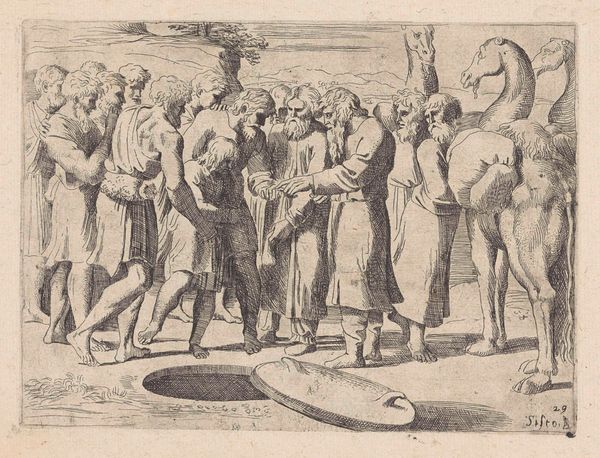

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before a captivating oil on canvas work whose provenance is anonymous, entitled "The Tupinambá’s Treatment of Prisoners of War", dating from around 1630. It currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is… unsettling. There's a detached, almost processional feel to this depiction of violence. It’s disturbing how orderly everything seems. Curator: It certainly is. Paintings like these from the baroque period were often commissioned to present ethnographic narratives to a European audience. This particular one tells a story of ritual cannibalism amongst the Tupinambá people of Brazil, as witnessed through a European lens. Editor: "Witnessed" is the key word there. It is an interpretation viewed through colonial ideology and presented as objective truth. Where does the reality of indigenous practices end and the construction of a narrative for justification begin? Curator: A valid and crucial question. We must consider what role images like this played in justifying colonization and shaping perceptions of indigenous peoples. Consider the visual cues—the emphasis on perceived 'savagery' in contrast to a presumed European 'civilization'. Editor: Exactly. The detached style only furthers this sense. The artist objectifies the scene, reducing individuals to types rather than allowing any empathy or complexity to emerge. And what purpose is the image intended to serve: Fear? Condemnation? Pure documentation? Curator: Likely a combination of all those. History paintings often carry heavy didactic loads, even when presenting cultural events. We're encouraged to consider power dynamics not only within the painting, but in the very act of its creation and circulation. Editor: This work pushes me to analyze who has the authority to tell stories and how visual representations impact our understanding – or rather, misunderstanding – of other cultures, particularly in light of pervasive colonial legacies. Curator: Ultimately, this image reminds us to critically evaluate how we look at history. These aren't neutral windows onto the past. Instead, they are constructed views reflecting agendas, prejudices, and power. Editor: I agree completely. Art forces a reevaluation of cultural impact in this historical context, where violence is visualized and truth is highly subjective. It underscores the complexities of representation itself.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In the 17th century, Europeans were enthralled by the original inhabitants of South America. Their (reputed) cannibalism spoke to the imagination. This painting was in the possession of the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam. Much of the scene is fantasized and says more about the Western perspective of the New World than the actual life of the Tupinambá people.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.