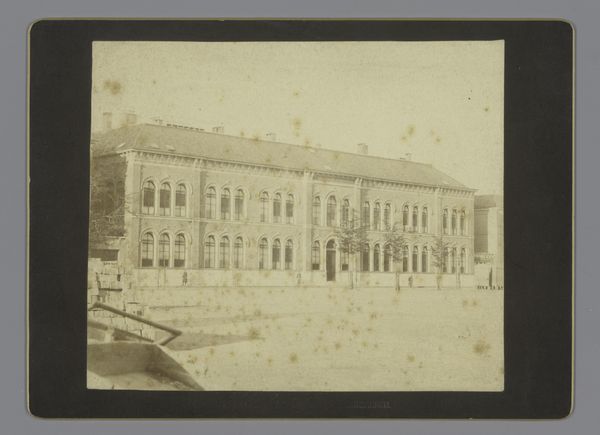

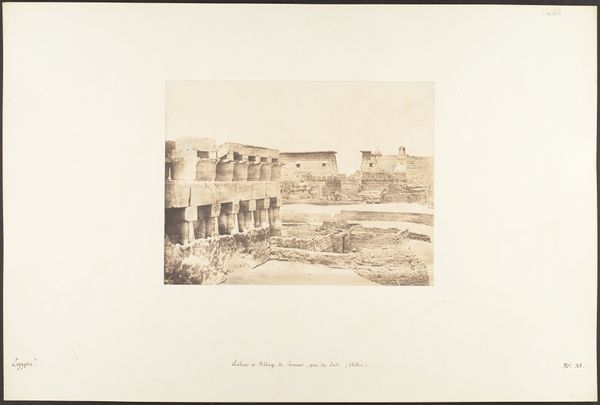

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

water colours

#

daguerreotype

#

house

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: It's a remarkably quiet image, almost spectral. A soft-toned cityscape, drained of color, giving it a timeless feel. Editor: Precisely. What we’re seeing here is a daguerreotype by Luigi Pesce, taken in 1858. It captures the Prime Minister’s House, or Nezanneh, in Tehran. This early form of photography holds significant weight historically, especially for the study of early urbanization in Persia during the mid-19th century. Curator: Yes, look at how Pesce positions the building. It almost looks as though he’s framing it for posterity, enshrining not just a place, but the power associated with it. You get that classic sense of Islamic design in the facade’s arches. Editor: Indeed. Those repeated arch motifs symbolize the gateway between the earthly and divine realms, an architectural trope found across Islamic structures. The minaret rising in the background reinforces this sacred presence, doesn't it? What fascinates me is that in early photographs of this kind, it was a huge investment and sign of status to be portrayed. Pesce may have even been capturing it for a particular person of importance. Curator: An interesting hypothesis! Considering the era, the mere act of documenting the Prime Minister’s residence using this nascent technology could have served to underscore modernization, but perhaps simultaneously it functioned to solidify power structures of the time. Editor: It also subtly points to the intersection of politics, identity, and representation. How the rulers chose to show themselves, to convey an impression through images of power to the public. I suppose, in some respects, little has changed. Curator: Absolutely, whether consciously or not, early photographs had a function to define public image. This glimpse offers more than a mere structure; it offers a snapshot of the sociopolitical dynamics at play. Editor: The enduring fascination of such a serene, seemingly simple photograph lies, perhaps, in its rich context—visual symbols intersecting history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.