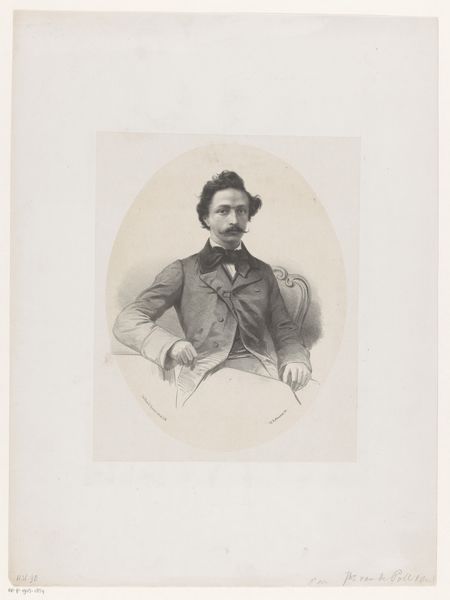

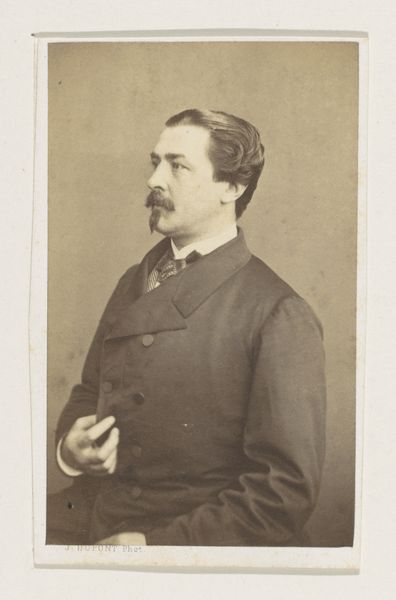

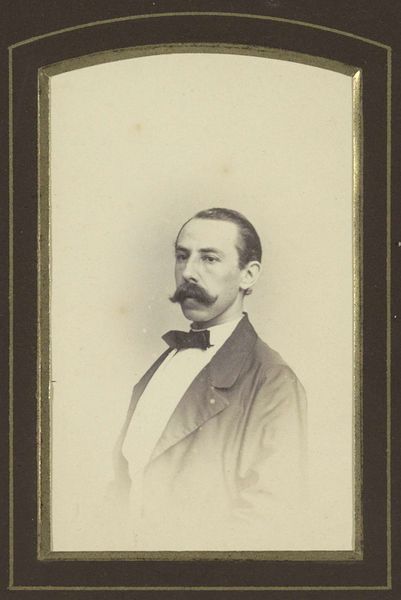

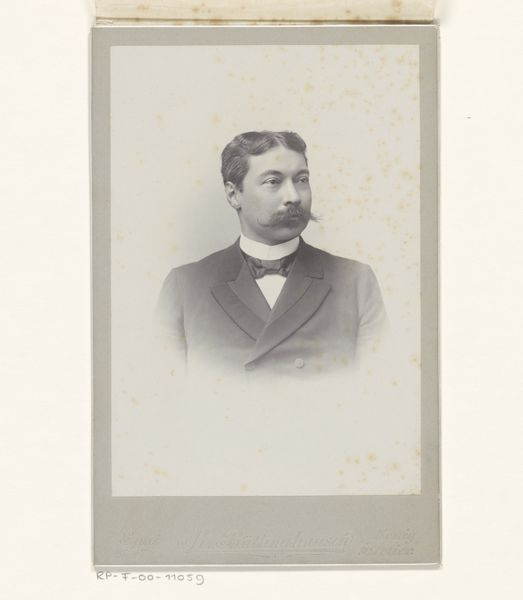

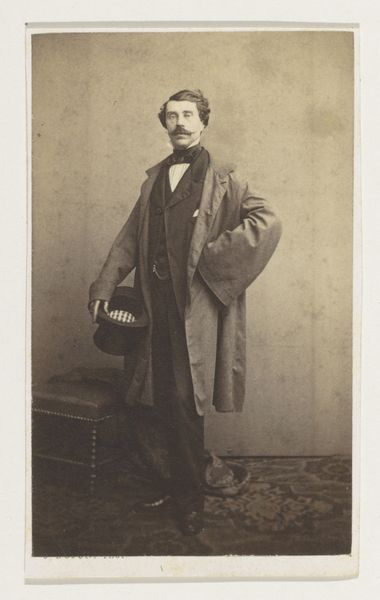

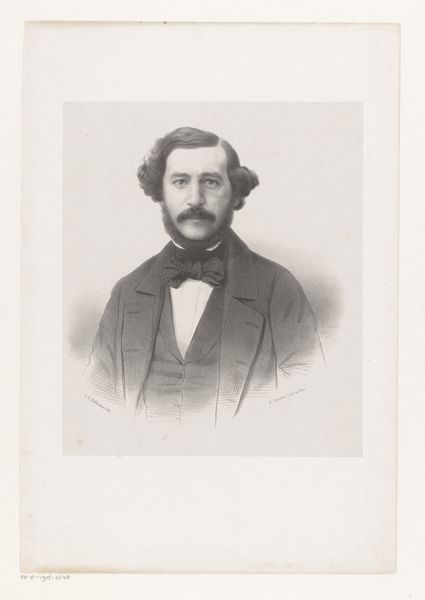

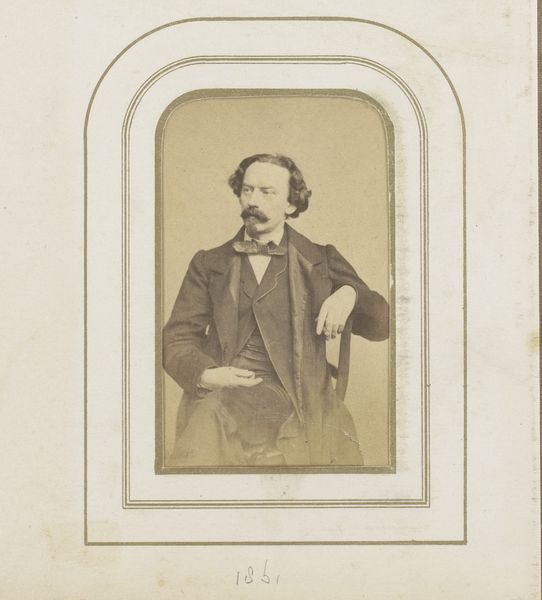

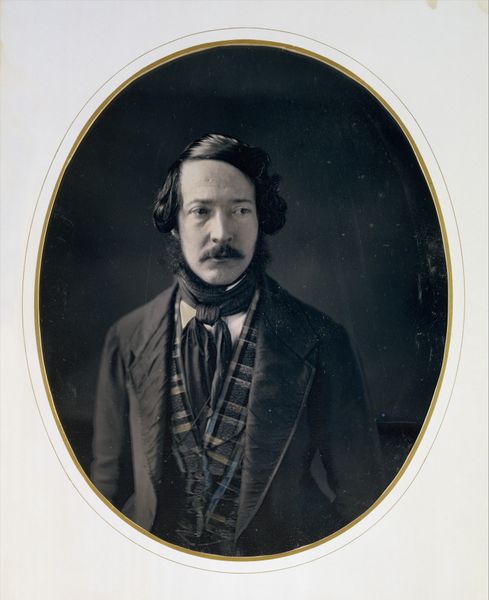

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

romanticism

#

portrait art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 555 mm, width 397 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jean-Baptiste Adolphe Lafosse’s 1848 daguerreotype, “Portret van Napoleon III,” held at the Rijksmuseum. I’m struck by how this early photographic process captures the somber mood and the weight of responsibility seemingly etched on Napoleon's face. What do you see when you look at this portrait? Curator: Beyond the immediate visual impression, I see a carefully constructed image meant to convey authority during a tumultuous period. 1848 was a year of revolutions across Europe. How does this portrait attempt to legitimize Napoleon III’s claim to power, especially considering the complicated legacy of his uncle? Editor: It seems to want to connect him to that legacy, but also to show him as more grounded, less… imperial, maybe? Almost like he’s trying to present himself as a man of the people, even with the fancy suit. Curator: Precisely. The daguerreotype, a relatively new technology at the time, allowed for a certain realism, contrasting with the more idealized paintings of previous rulers. Think about the choice of medium itself – photography democratizing portraiture. How might this accessibility have played a role in shaping public perception during a time of social upheaval? This technology allows us access to faces in a way the masses hadn't yet experienced. Does the image feel radical to you? Editor: It's a radical medium put in the service of… conservative power? The very act of photographing him might suggest progress, but it's being used to reinforce traditional hierarchies. It’s interesting how those power dynamics manifest. Curator: Exactly. Consider the historical context – France seeking stability after years of revolution. What role did images like these play in the construction of national identity and the consolidation of power? It makes me think of the similar portraits of other leaders—both in paintings, sculptures, and photography. Editor: That's a powerful point. I never considered how a photographic portrait could be just as carefully constructed and politically charged as a painting. Curator: Indeed. This photograph shows a unique moment where new technologies and age-old power struggles meet. I think it's the intersection that’s most fascinating here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.