drawing, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

surrealism

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 556 mm, width 724 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

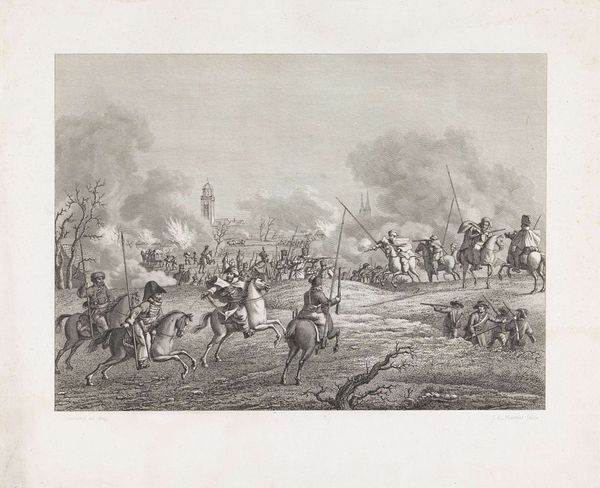

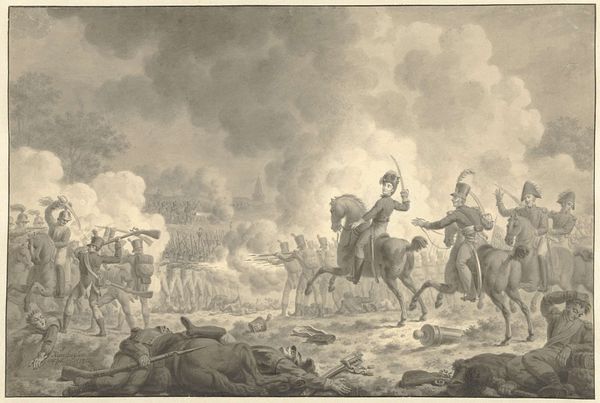

Curator: This compelling drawing is titled "Gevecht bij een dorp", or "Fight near a Village," created by Dirk Langendijk in 1805. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum and employs charcoal as its medium. Editor: The scene hits you immediately, doesn’t it? It's chaos rendered in muted tones, a frenetic energy barely contained within the frame. A swirl of combat, all grays and whites—almost dreamlike in its detachment, yet viscerally violent. Curator: Langendijk was well-known for his depictions of battles and military scenes. What's interesting here is the blend of romanticism and nascent realism, showing both the grand sweep of conflict and its brutal, personal impact. The rise of national sentiment and warfare dominated imagery in that era. Editor: And it's impossible to ignore that this 'grand sweep' is largely romanticizing violence, isn’t it? How does this narrative-art engage, or perhaps disengage, from the human cost? The village in the background seems almost indifferent. Curator: I think that detachment speaks volumes. The late 18th and early 19th centuries were times of revolution and upheaval, these grand narratives, were a way for the powerful to reassert a specific social and moral order. Editor: Look how bodies are contorted, nearly piled on top of each other. Langendijk has clearly mastered technique but perhaps that craft works to amplify the romantic ideal of power instead of calling into question whose stories get to be told, how war serves very particular interests, and at what cost. Curator: I agree. But there is an interesting tension in its use of charcoal. He presents the scale and sweep of armies in battle with something you would use for an intimate portrait. Editor: And yet that intimacy never extends to the victims, does it? Whose stories and experiences are flattened for this particular “grand narrative?" That’s the question I’m left with. Curator: Precisely. This piece reflects how institutions upheld hierarchies in history by shaping our perspective. Editor: Right, which is a good reason why art prompts us to question what’s centered, what’s not, and why these representations persist.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.