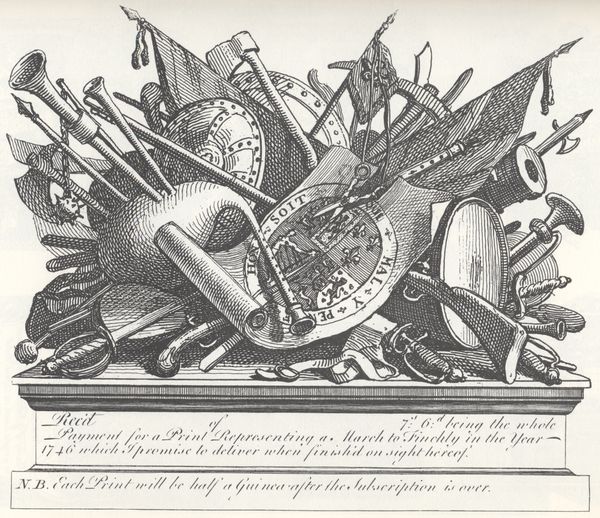

A Stand of Arms, Musical Instruments, etc. 1749 - 1750

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphic-art, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

#

weapon

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

engraving

#

arm

Dimensions: plate: 7 1/16 x 9 1/8 in. (18 x 23.2 cm) sheet: 7 7/8 x 10 1/8 in. (20 x 25.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This intricate engraving by William Hogarth, dating from 1749 to 1750, is titled "A Stand of Arms, Musical Instruments, etc." It's quite the collection of objects rendered with remarkable detail. What springs to mind for you initially? Editor: The first thing that hits me is the sheer density of symbolism! It's an almost overwhelming collection of objects—musical instruments jumbled together with weapons. There's definitely a strong feeling of ...conflict, or perhaps uneasy truce, created by the juxtaposition. Curator: That’s a perceptive observation. The image was designed to be a subscription ticket for Hogarth’s print “The March of the Guards to Finchley." Proceeds from subscription tickets supported the artist while he created the work, which comments on the social issues of his day. The apparent disorder contrasts with the political message. Editor: So, this jumble is deliberate? It certainly reads as more than mere decoration. The bagpipes especially stand out, centrally placed beneath what appears to be a royal crest. Is he making a specific statement about British identity at that time? Curator: It is layered. The bagpipes directly refer to the Jacobite rising. The arrangement as a whole suggests British military prowess in suppressing the rising. In placing weapons alongside musical instruments, Hogarth points to the complex relationships between war and peace, culture and conflict. The royal coat of arms obviously signals power. The subscription details add a layer about the business of art itself. Editor: The “business of art” angle really resonates. And thinking about it in the context of the Jacobite rising definitely deepens the layers of meaning. There’s a sense of forced harmony, of imposing order onto something inherently chaotic, visually represented here. It reminds us how political narratives often mask deeper tensions. Curator: Precisely. The image cleverly blends promotional intent with a commentary on the social and political climate of mid-18th century Britain, providing both immediate appeal and a deeper reading for those in the know. Editor: A potent reminder that even the most seemingly straightforward image can carry a multitude of meanings when viewed through the lens of history and cultural symbols. Curator: Indeed, making one appreciate the power, and even the trickery, of visual messaging in the 18th century— and, frankly, in our own time, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.