#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

childish illustration

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

cartoon carciture

#

sketchbook art

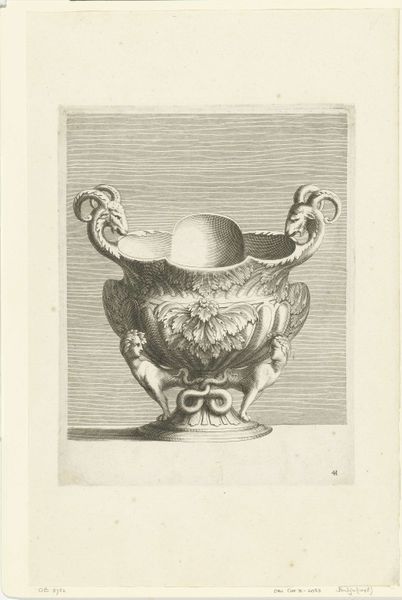

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this striking drawing, titled "Schenkkan met deksel," or "Pitcher with Lid," created in 1667 by Françoise Bouzonnet. What are your first thoughts? Editor: Well, I'm immediately struck by the materiality it suggests. Despite being a drawing, the object itself is ornate, and the metalwork implies both luxury and the skilled labor needed to produce something so elaborate. Curator: Absolutely. Bouzonnet, as a woman artist of her time, navigated a complex social landscape. Depicting this pitcher—a vessel, if you will—could be interpreted through a feminist lens, probing ideas of domesticity and women's roles in 17th-century society. The grotesque figure acting as a handle is an interesting gendered twist on common figurative decorations from that time. Editor: I agree. Notice the precise lines achieved with pen and ink, contrasted against the toned paper; it really gives depth to the depiction. The vessel isn't merely ornamental; it signifies function and trade, illustrating a moment where art serves everyday life. Who was producing pieces such as this and what was their place in society? Curator: Good question. Objects like this pitcher blur the lines between high art and craft, raising questions about value and artistry. Bouzonnet situates herself within and also outside these traditions through this rendering. The naked figure with laurel wreath almost parodies ideas about power, perhaps suggesting an intersection of femininity and power within elite social circles of the period. Editor: Exactly! And considering the political turmoil across Europe at that time, could this opulent display represent more than just lavishness? What about wealth accumulation during intense conflict? The pitcher is presented through a crafted illustration; labor becomes the key factor for unlocking potential narratives. The making of the image asks us to see who could commission such a valuable object and what were the global sources for its manufacture. Curator: Precisely. We see how Bouzonnet is prompting conversations that remain pertinent today—who has access, what does luxury signify, and who produces the very items we venerate? Editor: It also asks how do our personal consumption habits contribute to labor practices or potentially create more division based on capital and material accumulation. Curator: An object like this is much more than decoration; it acts as a flashpoint for the intersectional narratives shaping identity and history. Editor: I agree entirely; by focusing on materials and means, we better understand both the economic underpinnings and the hands that bring them into being.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.