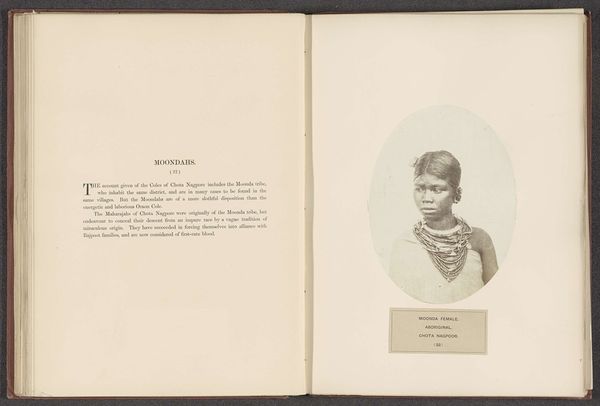

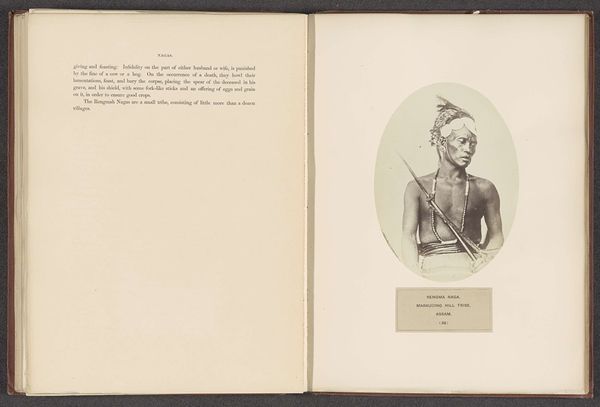

Portret van een onbekende Korewah man met een pijl-en-boog uit Chota Nagpur before 1868

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

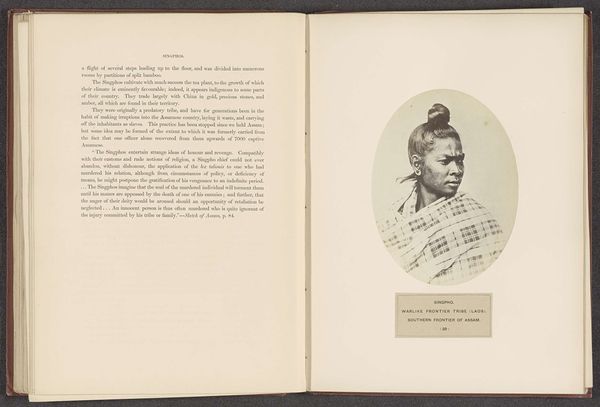

Curator: This albumen print, "Portret van een onbekende Korewah man met een pijl-en-boog uit Chota Nagpur," comes to us from before 1868 and was captured by Benjamin Simpson. My initial feeling is the stillness, how formally this individual is posed within the oval frame, so resolute. Editor: It is a fascinating use of the photographic medium for what feels like a deeply colonial project. The image functions less as an individual portrait, and more as a piece of anthropological data-capture, framed by the racialized power dynamics inherent to the era. Look at the staging - bare-chested, the tools of survival presented like props…it's all highly constructed. Curator: Absolutely. And when we consider the albumen printing process, each print requires a treated paper base prepared with egg whites, and a silver nitrate solution to create the light-sensitive surface. Then there’s the complex process of developing, washing, and fixing to make this unique print. A material lens emphasizes the chemical transformation, and artisanal labor in its making. Editor: Which complicates the straightforward “documentation” narrative. Whose story are we actually seeing? Who has control over representation here, and what colonial gaze informed that vision? How were these images received in Europe at the time, versus how they might have been understood by the man himself, or by members of his community? There are layers upon layers of meaning imbued by both social and historical contexts. Curator: Indeed. Though this work can function as evidence of anthropological documentation during its period, viewing the physical construction complicates the way we look at this individual as subject. We see then not only an image of someone, but the result of chemical and manual processing, reflecting time and material resources utilized for knowledge production during this era. Editor: The photographic act is never neutral; it’s always embedded in networks of power, informed by pre-existing biases, cultural assumptions and specific purposes. In this case, the image feels weighted with colonial ambitions and skewed portrayals of Indigenous identity. Thinking about the consumption of such images adds further dimensions to that complex network of coloniality. Curator: Thinking of how it has come to be now is equally important. I think looking at the labor required to bring it to life helps show the material qualities present, and lets us ask these important questions about labor. Editor: Ultimately, analyzing how such photographic representation shaped and reflected historical power imbalances feels incredibly crucial. It compels us to critically examine the enduring legacies of colonialism within visual culture, ensuring conversations about historical context remain active.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.