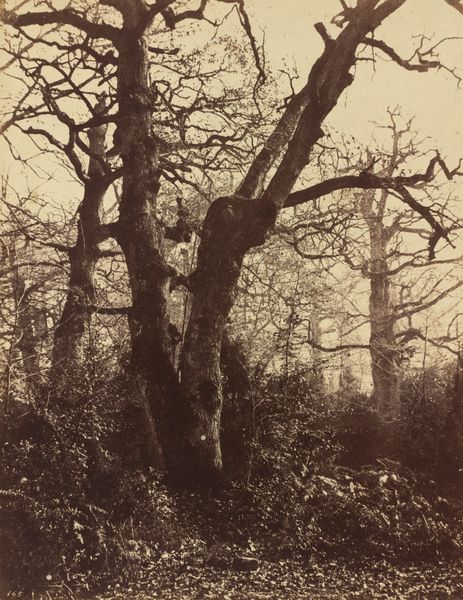

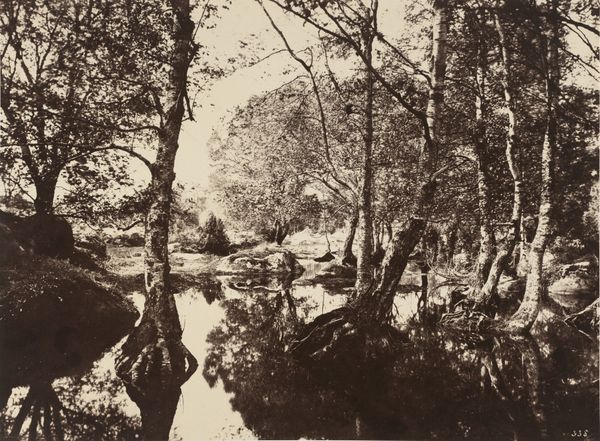

Dimensions: image/sheet: 25.7 × 35.2 cm (10 1/8 × 13 7/8 in.) mount: 42.4 × 59.4 cm (16 11/16 × 23 3/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Right now we're looking at Lèon Gèrard’s "Landscape, Montebello," a gelatin silver print from around 1860. It's incredibly still. The light is diffused, the water looks almost like liquid smoke. What catches your eye the most about it? Curator: It's funny you say "still," because the blurred water feels so full of unseen energy, like the land itself is exhaling. But, beyond that palpable sense of place, I see Gérard wrestling with photography's role. Think about it – photography, barely a toddler, trying to be taken seriously as 'art'. Is it just a recording device, or can it capture something deeper? Editor: So, you're saying Gérard is intentionally blurring the line between documentation and… feeling? Curator: Precisely. That dreamy haze, that deliberate softness…it’s all about suggesting mood, emotion, a subjective experience. He isn't just showing us Montebello; he's whispering a secret about it. The monochrome palette really contributes too, don’t you think? It distances the work from reality, making it about suggestion and nuance. Editor: It definitely takes the image into another realm. And to think, this was 1860, so early in photography's history! I guess I hadn’t fully considered photography as something that wasn’t *always* trying to capture every single detail as accurately as possible. Curator: Photography, at its best, lets us play peek-a-boo with reality. Thank you, Léon Gérard! It definitely makes you appreciate how artistic the process of photography really is. Editor: It's given me a whole new way of looking at 19th-century photography. I came into this conversation expecting straightforward landscapes, and now I am looking at whispers and secrets.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.