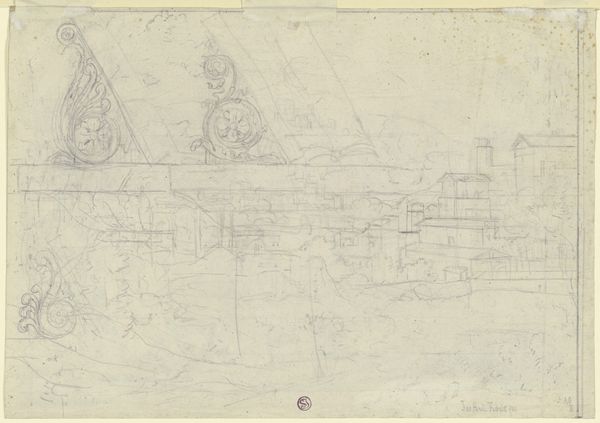

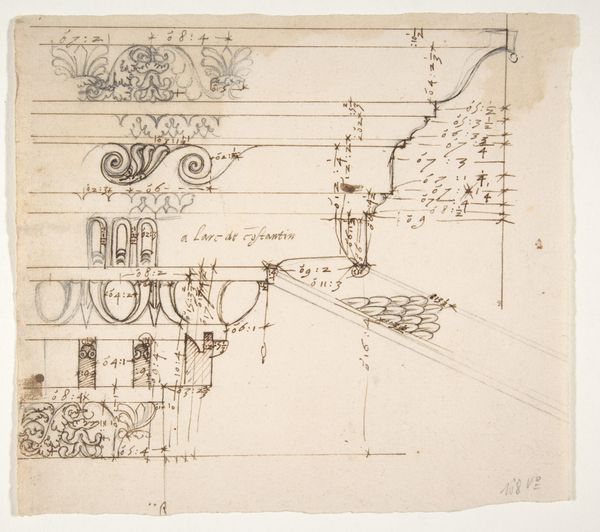

Studienblatt_ Geflügelte Schlange in einem Giebelfeld sowie Hieroglyphen 1829

0:00

0:00

drawing, ornament, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

ornament

#

16_19th-century

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

paper

#

egypt

#

sketchwork

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is Friedrich Maximilian Hessemer's "Studienblatt: Geflügelte Schlange in einem Giebelfeld sowie Hieroglyphen," created in 1829 using pencil on paper. There's a fascinating stillness to these sketched Egyptian motifs, almost as though the artist captured them in a moment of hushed reverence. What strikes you about this work? Curator: I see a dialogue between cultures, a 19th-century European artist grappling with the visual language of ancient Egypt. Hessemer isn't just copying; he's interpreting. The act of sketching, of studying these forms, becomes a kind of translation. How does the serpent, a potent symbol across cultures, resonate with you in this context? Do you perceive a power dynamic in Hessemer's gaze? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the potential power dynamic, but it makes sense. I mean, a European artist studying and representing Egyptian imagery... I guess it could be seen as an act of appropriation, depending on his intentions and how he contextualized it. But is there also room for genuine appreciation and cross-cultural understanding? Curator: Precisely! It’s rarely simple. The 19th century was rife with Orientalism, where the "exotic" East was often filtered through a Western lens, reinforcing stereotypes. However, it was also a time of increasing archaeological discoveries and a growing fascination with understanding different civilizations. Hessemer’s work can be viewed through both lenses. What effect does the medium itself – pencil on paper – have on your perception of these ancient forms? Editor: I think the pencil sketch aspect softens the images, in contrast with the stone reliefs and carvings where those images were seen in Egypt. I guess it also hints that he is re-interpreting or translating the message in the original works, which you mentioned before. Curator: And by softening these images does he, perhaps, unintentionally participate in the problematic practice of softening ancient Egyptian agency by re-contextualizing it? These visual decisions were conscious choices that may lead to re-evaluations. Editor: Wow, I hadn’t thought of that. I definitely see it differently now. Curator: That’s the beauty of art history; it prompts us to continuously re-evaluate our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.