![Fotoreproductie van schilderij Madonna met kind door Sasso Ferrato [?], S. Maria Formosa te Venetië by Carlo Naya](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzA5Y2QyMTU4LTZiYjQtNGQ0ZS05ODdlLTZkM2Y0ZTljNGVmZi8wOWNkMjE1OC02YmI0LTRkNGUtOTg3ZS02ZDNmNGU5YzRlZmZfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

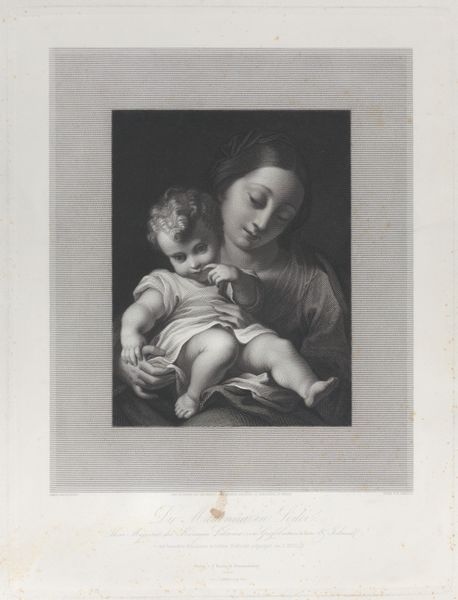

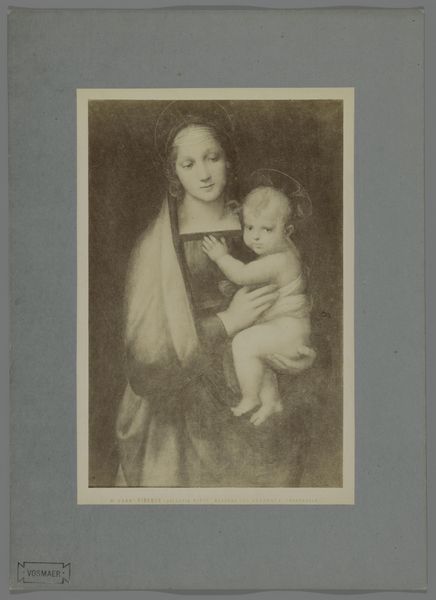

Fotoreproductie van schilderij Madonna met kind door Sasso Ferrato [?], S. Maria Formosa te Venetië c. 1860 - 1880

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

italian-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: height 339 mm, width 264 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a gelatin-silver print from around 1860 to 1880 by Carlo Naya. It's a photographic reproduction of Sassoferrato’s “Madonna and Child,” located in S. Maria Formosa in Venice. The photograph itself feels rather subdued, almost faded, lending it a timeless quality. How does this reproduction engage with the history it references? Curator: That's a great observation. These photographic reproductions became increasingly common, serving to democratize art. How does Naya's choice of photography change the experience compared to seeing the original painting? Editor: Well, it loses the original's color and texture, becoming more about form and light, perhaps? Curator: Precisely. Think about it in the context of the rise of tourism and mass media. This image made the *Madonna* accessible, no longer confined to a specific church in Venice. But also consider who had access to photography. Were these images really reaching the masses, or catering to a growing middle class eager to consume culture? Editor: That’s a really good point. I hadn’t thought about it in terms of access and social class. It’s like a form of early art appropriation, but with a different goal. Curator: Exactly! The "aura" of the original is somewhat diluted through mechanical reproduction. It's worth noting that even though the photographer here is documenting someone else’s image, the result gains a life of its own through its very distribution as commodity and art object, raising the question of who becomes authorized as “artist.” How does that strike you? Editor: It definitely makes me rethink what "originality" means in art history. Thanks for shedding some light on that! Curator: My pleasure. Hopefully, you see now how deeply intertwined art is with its historical and social context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.