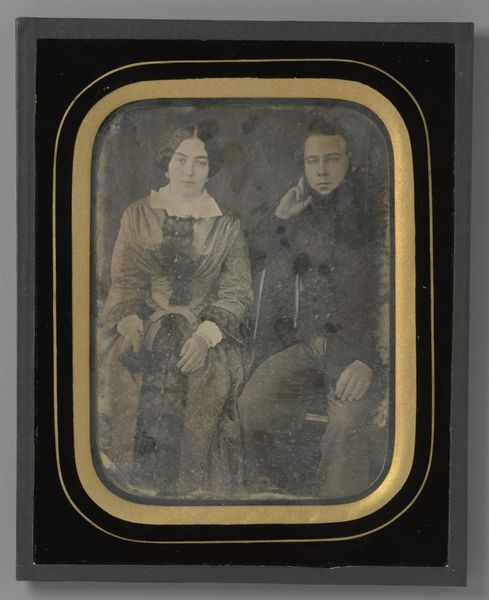

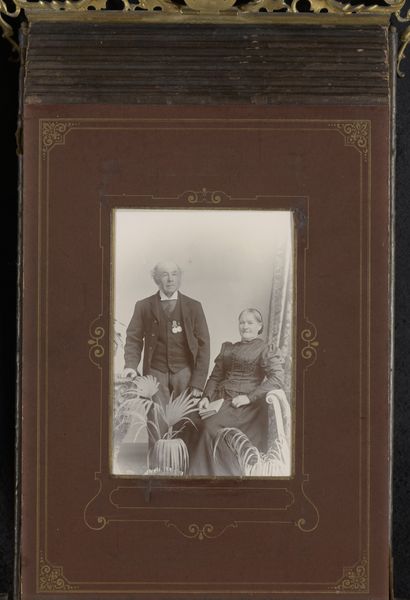

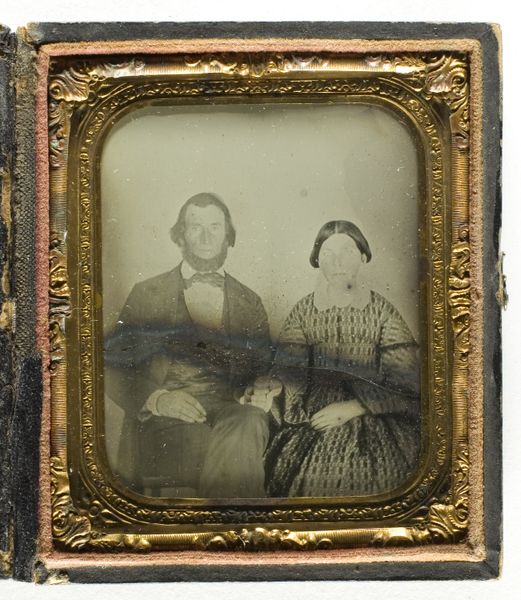

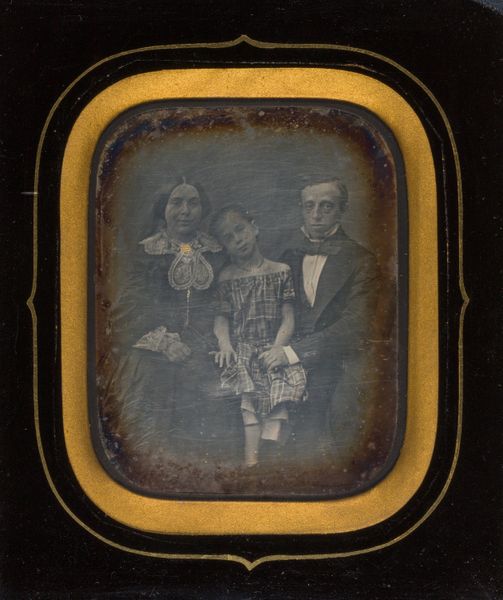

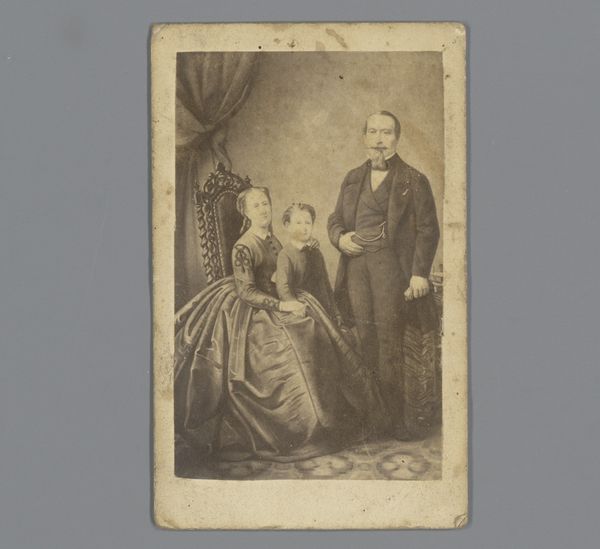

Portret van een onbekende man en vrouw voor een geschilderd stadsgezicht c. 1850 - 1860

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

realism

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 132 mm, height 250 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an anonymous daguerreotype from around 1850 to 1860, titled "Portret van een onbekende man en vrouw voor een geschilderd stadsgezicht," or, "Portrait of an Unknown Man and Woman Before a Painted Cityscape." The greyscale gives it such a somber feeling. I'm curious, what do you see when you look at this? Curator: I see a potent illustration of the democratizing force of early photography and the materiality of its production. Look at the clothing, likely not extravagant but certainly respectable. Photography offered access to portraiture beyond the wealthy elite. Editor: That's a really good point. It's easy to focus on just the people, not the means by which the image was made. Curator: Exactly. And consider the hand-crafted nature of daguerreotypes: the preparation of the plate, the lengthy exposure time requiring subjects to be still, the delicate chemical processes. This isn't just pointing a camera and clicking. Editor: It sounds like it would take ages! So many things could go wrong, I'd imagine. Curator: Indeed. And that backdrop! Painted. What does that tell us about the studio, its aspirations, its understanding of "art?" It isn't just about representation, it’s about commerce and social aspiration too. Editor: So, the making of it, and even the set, is kind of a social mirror? Curator: Precisely. How labour and class operate even at this scale. These photographic studios represent this cultural intersection, in its infancy. The labor to run the space, secure the shot, the sitter's means, are all key here. Editor: I’ve learned to look beyond just the image itself to understand the conditions in which it came to be, and what purpose it may have served. Thank you! Curator: Indeed! Considering the processes of creation encourages richer and multifaceted meanings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.