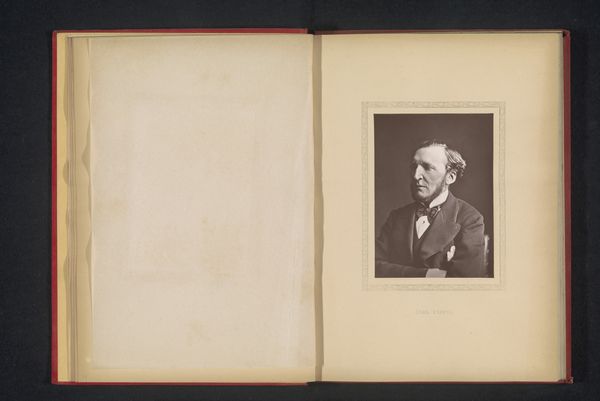

photography, gelatin-silver-print

portrait

aged paper

script typography

old engraving style

personal journal design

photography

personal sketchbook

hand-drawn typeface

gelatin-silver-print

pen and pencil

sketchbook drawing

delicate typography

realism

historical font

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

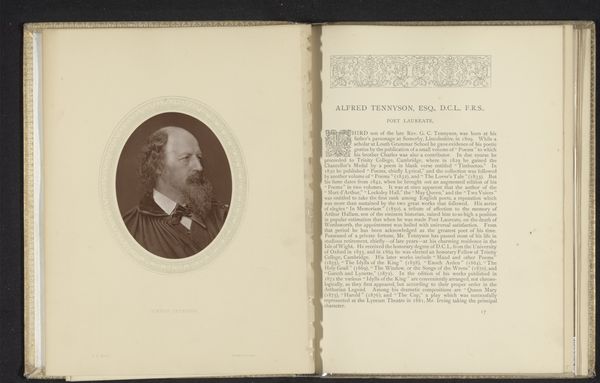

Editor: Here we have a gelatin silver print dating from around 1875-1880, a portrait titled "The Right Hon. Baron Carlingford, K.P.". It's presented as an open book, with the portrait on the left page and a blank page opposite. There's something almost haunting about this image, a kind of melancholic air about the man and the format. What historical or social context informs this kind of presentation? Curator: That melancholic air is quite telling, isn’t it? Photography during this period was still imbued with the gravitas previously reserved for painted portraits of the elite. Displaying it in a bound volume like this speaks to the formalization of memory, almost creating a personalized, portable monument to Carlingford's social standing and legacy. Think about who would have commissioned and owned such a book. What purpose did it serve in their social circles? Editor: So, it's less about personal sentimentality and more about projecting and preserving status? Like a Victorian-era LinkedIn profile? Curator: Precisely. Consider the deliberate staging. The crispness of the gelatin silver print versus the suggestion of a handcrafted, personal item. The visual tension highlights the controlled image Carlingford wants to project, contrasted with the intimacy a book suggests. Where else might such photographs been collected and displayed during this era? Editor: Maybe in clubs, or institutions where men like him gathered? Or perhaps photograph albums designed to display social networks. It does make me wonder about the role of photography in shaping public perception back then, creating almost official "records." Curator: Indeed. The power dynamics inherent in image production and dissemination are key. Who had access to the technology, and therefore, who controlled the narrative? Think about what we aren't seeing – the working classes, for instance. It is important to ask what social purpose photography serves in creating that historic record. Editor: It's interesting how something that seems so straightforward, a simple portrait, can open up so many avenues of inquiry about power and representation. Thanks for shedding light on the broader context! Curator: My pleasure! These kinds of images prompt us to really consider the politics embedded in portraiture, especially concerning the representation of elite figures in shaping cultural memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.