Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

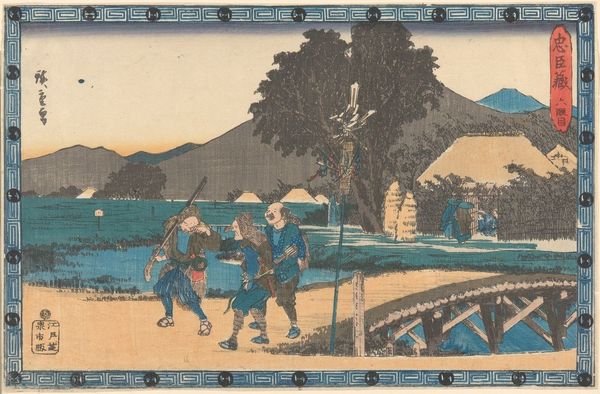

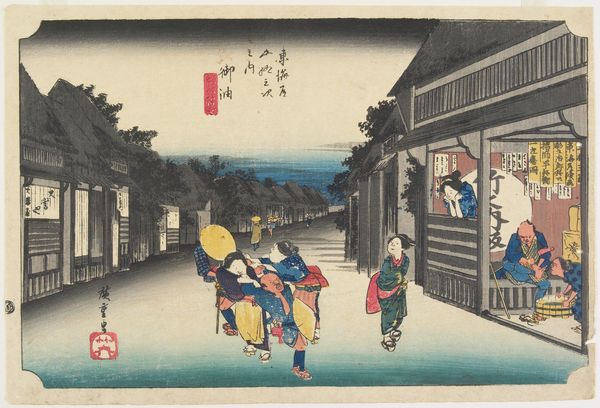

Curator: Allow me to introduce "Mishima," a woodblock print from 1906 by Utagawa Hiroshige, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is one of muted stillness. It's serene, almost dreamlike, despite depicting a scene bustling with travelers. Curator: That serenity belies the socioeconomic realities underpinning ukiyo-e art of this period. Hiroshige wasn't just capturing a pretty landscape, but also reflecting the rigid social hierarchies and labor practices of Tokugawa-era Japan. Consider the figures carrying the palanquin—their labor literally supporting those of a higher social standing. Editor: The palanquin immediately drew my eye, its symbolic weight undeniable. It represents not just transport but status. Notice how the geometric patterns of the passenger’s robe contrast with the more organic, flowing designs on the carriers' garments—visual cues signifying class distinctions. Also the presence of Shinto gates suggests spiritual overtones. Does the traveler also make a religious journey, perhaps? Curator: Absolutely. The journey itself held immense social and spiritual importance. These prints weren’t merely decorative; they were circulated within a burgeoning commercial culture. Pilgrimages and travel became increasingly accessible, while the artwork documented the shifting cultural landscape with new kinds of tourism enabled by an era of relative peace and prosperity controlled and enforced through severe policies of the Shogunate. Editor: And beyond this socio-historical frame, Hiroshige masterfully employs the stylistic conventions of Japonisme that fascinated western artists. Observe how the linear perspective flattens the background, almost abstracting the mountain, a powerful icon within the Asian aesthetic traditions. This reduction allows the procession to dominate the scene. Curator: The interplay between the individual and the collective, personal ambition and social expectation, I think it's brilliantly captured, right? Editor: Indeed, it’s more than just a landscape; it's a carefully constructed narrative about social power, cultural exchange, and the symbolic significance embedded within everyday scenes. Curator: Exploring this intersectional view can allow us to critically consider our relationship with representation of this history and how class, labor, and power intersect in shaping lived experiences then and now. Editor: A poignant visual memory preserved.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.