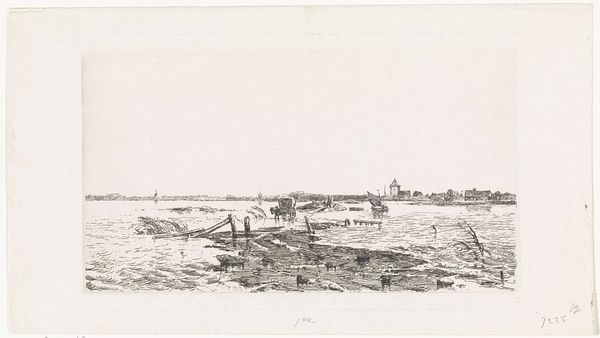

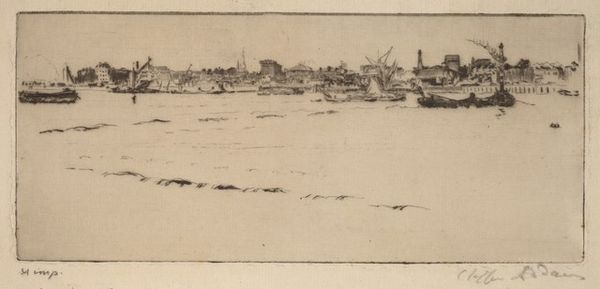

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

form

#

ink

#

realism

#

monochrome

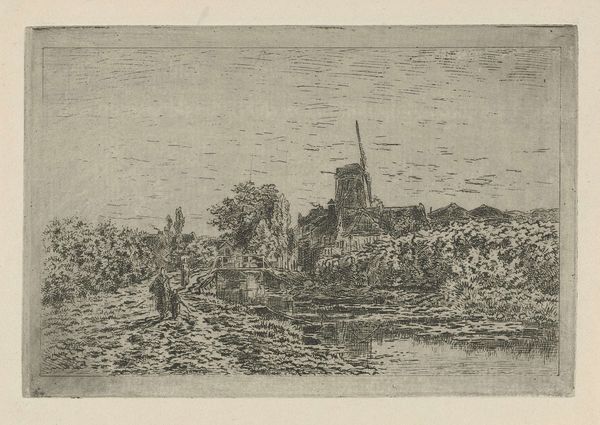

Dimensions: height 71 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

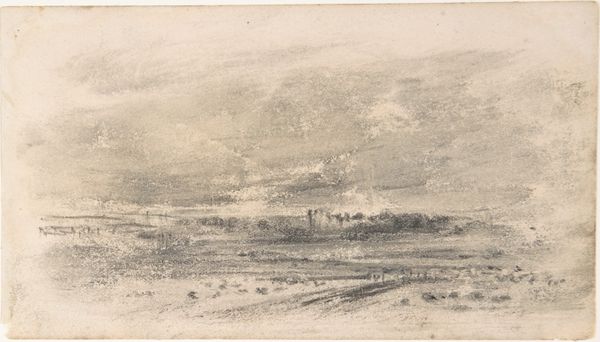

Curator: This monochrome etching, "Landschap met een koe," or "Landscape with a Cow," comes to us from an anonymous artist, created sometime between 1630 and 1700. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you initially about this scene? Editor: There's an immediate sense of openness. Despite the small scale of the etching, the artist conveys vastness. I’m also struck by the contrast. The foreground feels heavily worked with darker lines and figures, fading to a lighter, almost dreamlike, distant landscape. Curator: The technique certainly reinforces the effect of depth and distance, doesn't it? And yet, there's also a deliberate flattening, perhaps typical of the Dutch Golden Age approach to landscape, presenting an almost symbolic order onto nature. Consider, for instance, the way figures populate the planes. Editor: That tension is precisely what grabs me! The people, rendered in varying degrees of detail, point to socio-economic realities, rural life marked by labor and leisure. That lone figure walking towards us could be seen as embodying labor, walking from one realm into another, with the seated individuals almost representing land ownership and an entirely different set of freedoms, maybe. Curator: It is a lovely intersection of daily life and timeless landscape. Speaking of timeless, notice how certain forms—a rudimentary structure of some kind, a gathering of figures—repeat like motifs in much earlier landscapes; in, for example, early printed books or even medieval tapestries. The simple act of seeing and etching a cow holds within it layers of meaning carried through the centuries. It anchors us in an unfolding visual lineage. Editor: Yes, and thinking of cows within landscapes during this period is interesting. There is, after all, a reason that landscape and pastoral imagery enjoyed popularity at that moment in history. The rise of trade and merchant wealth meant that land and its yield were deeply connected to nascent Dutch identity formation. It could almost be a propagandistic piece in that respect, one that ties the national image with an image of agrarian plenty. Curator: Precisely! We look at it now and see a "simple landscape," but it resonated powerfully in its time. It provided an image that the emerging, self-fashioned nation could celebrate and hold onto. The landscape in itself becomes an enduring icon. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about this further contextualizes our present moment, showing how art continues to inform national identity and values. It has been a fascinating examination!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.