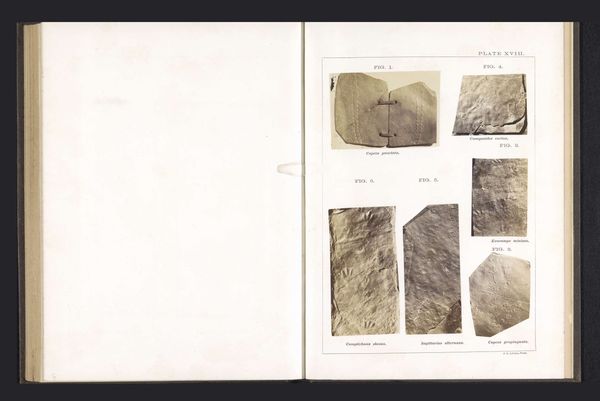

print, daguerreotype, photography

# print

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

Dimensions: height 313 mm, width 232 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

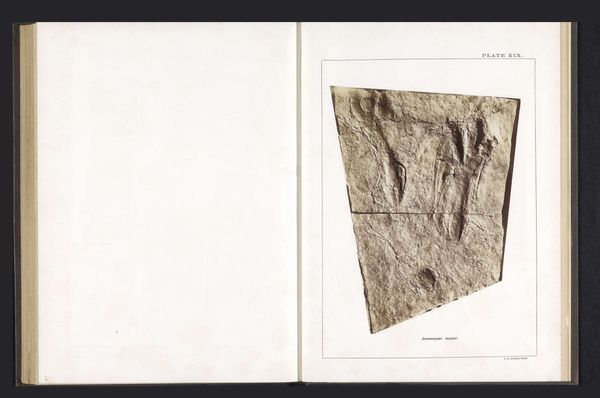

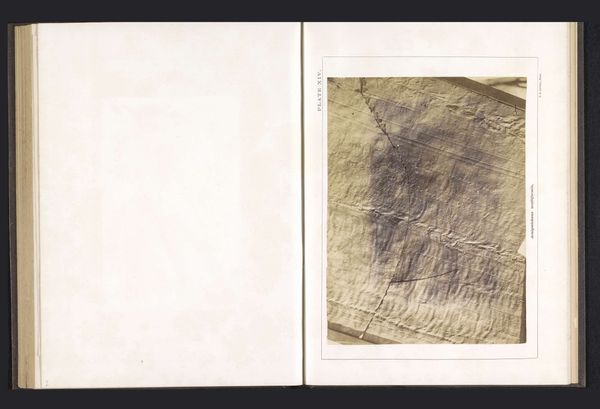

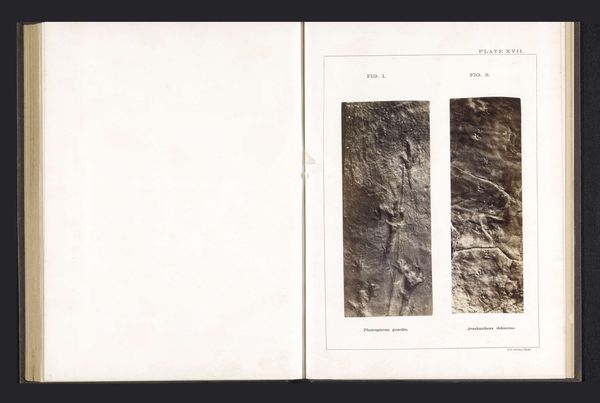

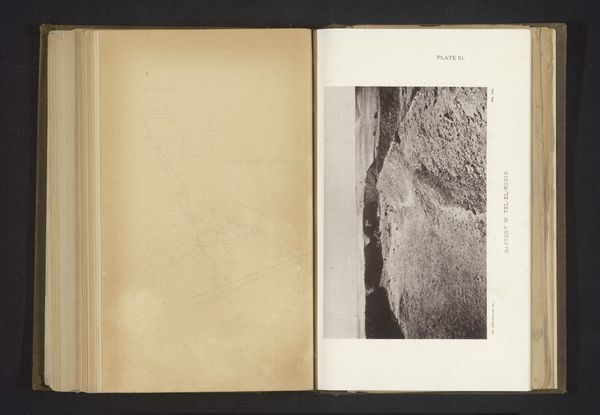

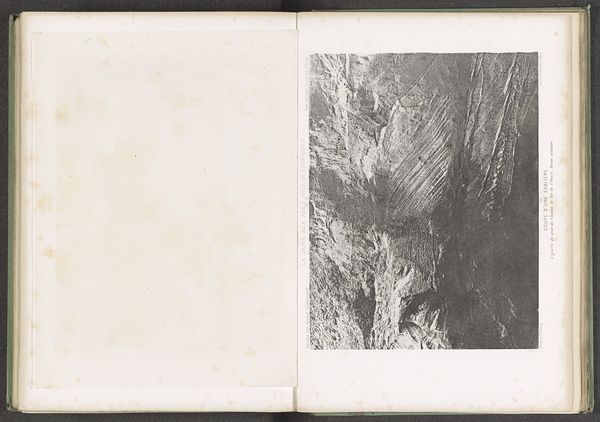

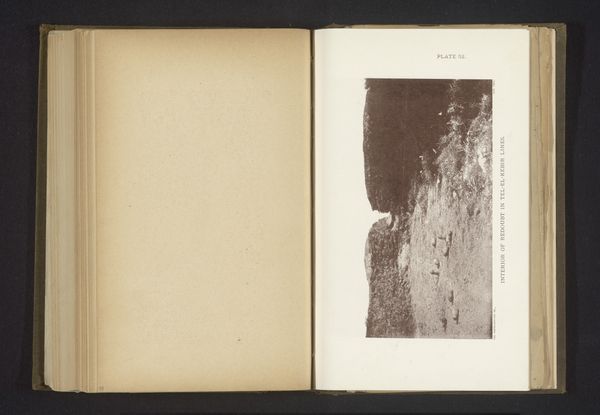

Curator: This intriguing print, likely a daguerreotype, is titled "Pootafdruk en een spoor van een staart"—or "Footprint and a trace of a tail"—and it's attributed to J.L. Lovell from before 1863. It depicts photographs of fossilized traces. What's your immediate take? Editor: A raw record of something incredibly ancient, presented with almost scientific detachment. I’m drawn to the textures. Look at the sedimentary layers in the top photograph. I wonder about the labor to obtain this. The mining, preparing and processing these prints... What was Lovell's working process? Curator: Given the title, it seems that the image seeks to preserve some evidence, but the lack of environmental or archaeological context, and our contemporary separation from that long ago world of fossilization and evolutionary transformation, amplifies the sense of mystery. Don’t you find that to be typical of relics? Editor: I suppose that in taking something from the world to create this image it’s made precious by our modern day looking in and thinking, "this thing has been taken, for what purpose?" And, from a production standpoint, there’s the chemical labor in making a daguerreotype in the mid-19th century. Do we know why Lovell focused on this specimen? What specific claims were being investigated here? Curator: The visual signifiers feel purposefully ambiguous: foot... print. What sort of creature? What manner of record? The open-ended, primordial question marks really drive its appeal for me. Perhaps it's suggestive of early ideas about evolution or geologic change... a Victorian thirst to grasp an unimaginably deep timescale. Editor: Agreed. Even the geometry plays a role, look at the line of stratification juxtaposed against what might be the geometric impression of that 'tail'. Was Lovell working for hire, cataloging a collection? And what processes made such an affordable circulation possible? I would want to explore more deeply, here. Curator: Exactly. Thinking of deep time makes me realize this artifact also acts like a footprint into how humans catalog and interpret history, or maybe natural history would be the better way to put it. It captures both geological and intellectual formations simultaneously. Editor: Yes! Seeing this, I am moved by these very direct markers into understanding labor and materials. They prompt us to delve into the intellectual and historical construction of what we now consider evidence, memory, knowledge and fact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.