#

figurative

#

character portrait

#

portrait image

#

portrait

#

portrait reference

#

portrait head and shoulder

#

portrait drawing

#

facial portrait

#

fine art portrait

#

celebrity portrait

#

digital portrait

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

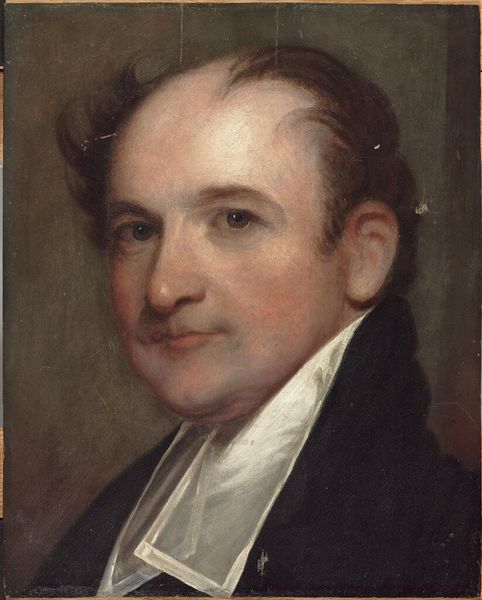

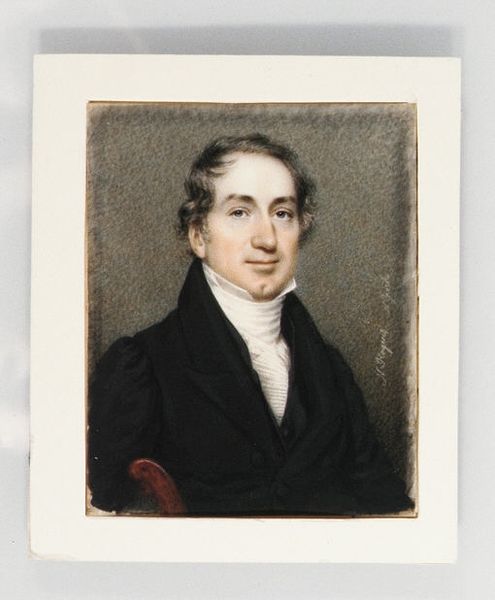

Curator: Standing before us, we have Thomas Sully's portrait of William Gwynn, completed in 1821. Editor: He looks like a man burdened by secrets. There’s something weighty about the sitter's gaze, and the subdued palette amplifies this pensive mood. Curator: Indeed. Sully, active during a period of burgeoning American identity, catered to the elite, providing visual representations that reinforced social hierarchies. The very act of commissioning a portrait like this spoke volumes about status and self-fashioning. Editor: And consider the materials, the tangible connection to that social structure. The weave of the canvas, the pigment created through potentially exploitative labor… even the artist’s labor is a key part of how we consume this piece today. Who produced the pigments and canvas, and under what conditions? Those questions impact our understanding of the work's original context. Curator: That is very insightful. Furthermore, the location where the painting would have been displayed–most likely within a private residence–was a carefully controlled environment designed to project an image of power and cultivated taste. It’s not simply about personal likeness, but about embedding oneself within a historical narrative. Editor: Right, but notice how Sully's rendering softens Gwynn’s features, perhaps idealizing them ever so slightly? That plays into the narrative, blurring the lines between documentation and fabrication of an ideal persona. Curator: Exactly. It invites reflection on the relationship between the patron and the artist. What unspoken agreements dictated the final image? And, more broadly, what influence did portraiture have in solidifying notions of aristocracy in America? Editor: Ultimately, art is never just "art." The creation and display of art is intrinsically linked to class, commerce, and the stories a society chooses to tell about itself through tangible objects like pigment and canvas. Curator: Precisely, reflecting on it now, this portrait encapsulates so much more than just an individual. Editor: Indeed, it really opens a door into contemplating labor, materiality, and the politics embedded within an artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.