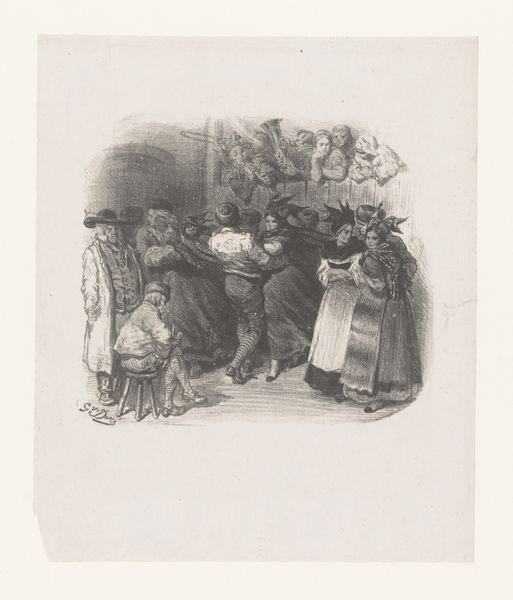

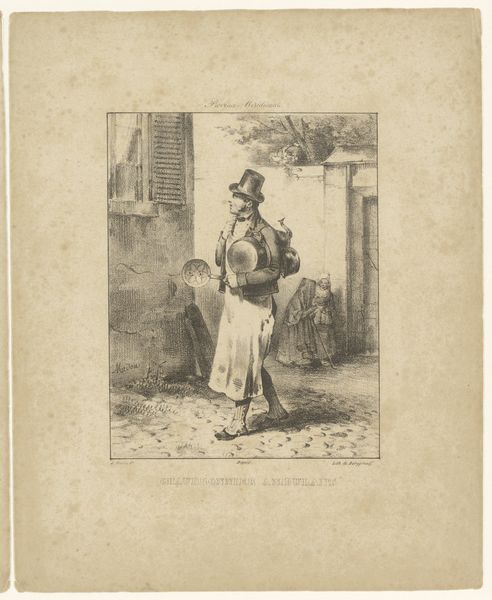

drawing, lithograph, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

group-portraits

#

romanticism

#

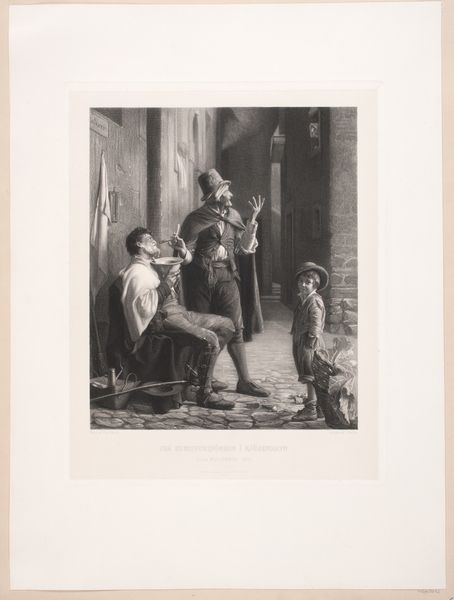

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 355 mm, width 259 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There’s such an immediacy to Nicolas Toussaint Charlet's "Old Sailor Smoking a Pipe in a Pub," done in 1828. It feels as though we’ve just walked in on this scene. Editor: You can almost smell the stale beer and tobacco. The lithographic medium contributes a rough texture, emphasizing the working-class environment. You know, pipes weren't cheap back then—they signify a level of material comfort for the sailor. Curator: Oh, absolutely. But it's also the communal aspect that speaks to me. It’s about kinship and shared experience among these weather-beaten faces. What do you imagine they are sharing? Is it songs, lamentations, boasts? Who knows what adventures these walls hold, or don’t? Editor: It is fascinating to consider the physical creation. This isn't some grand oil painting destined for a palace, but a print. Multiple copies could be produced and distributed, creating a kind of artistic democratization reflecting and representing the everyday lives of regular folk. It makes me curious who purchased this, and where it was hung. Curator: Right, it dissolves a hierarchy. And there’s such humor in Charlet’s approach, not overly sentimental, but acutely human. Notice the single figure in the center of the room, on the right side of the foreground, leaning against what looks to be a barrel. Editor: Sitting or leaning against a barrel—likely repurposed and a reflection of material practicality. The tankard beside the barrel. This speaks to reuse and economy in a period increasingly marked by material culture. It reflects the social milieu far more than any artifice. Curator: But also, this moment, forever held still. Someone cared about these sailors, about freezing this moment. That gives the drawing such a resonance. There’s an intimacy—and a sense of a story left untold, floating in the haze of smoke and drink. It makes you think and even long for whatever it is this close gathering signifies to them. Editor: Absolutely. It’s in this focus on ordinary subjects and replicable media that Charlet captures a crucial piece of cultural history. What’s depicted is important, but the printmaking process itself expands the meaning—this artwork's accessibility. It connects us to a broader narrative about labour and the consumption of imagery in the early 19th century. Curator: Well put. It shows how seemingly simple imagery can echo long after its ink dries and pages have turned. Editor: Indeed. And in doing so, reveal much about not just artistic intention, but a system of material conditions that both shaped it and were shaped by it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.