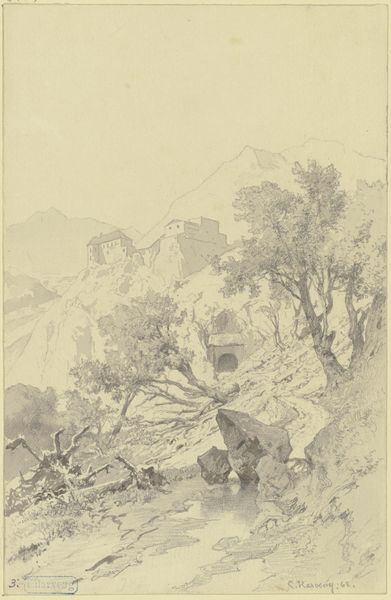

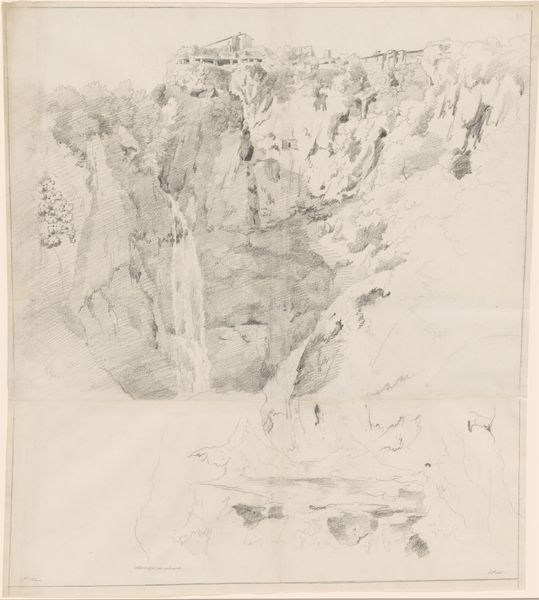

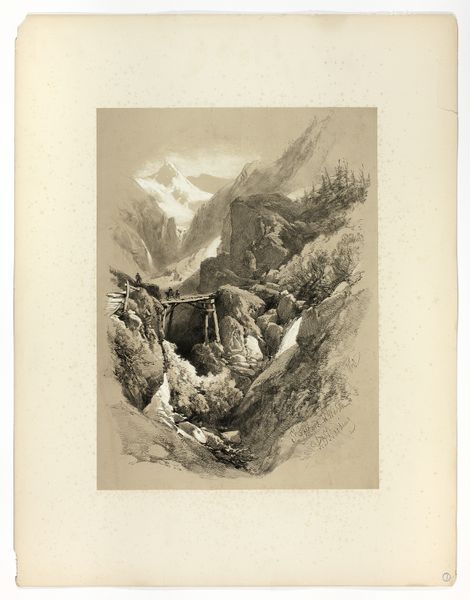

drawing, charcoal

#

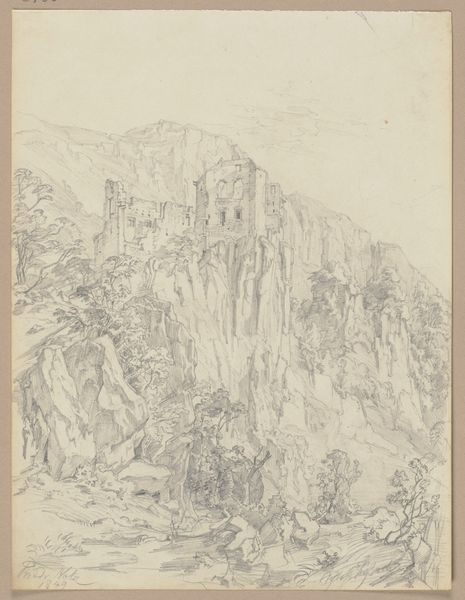

drawing

#

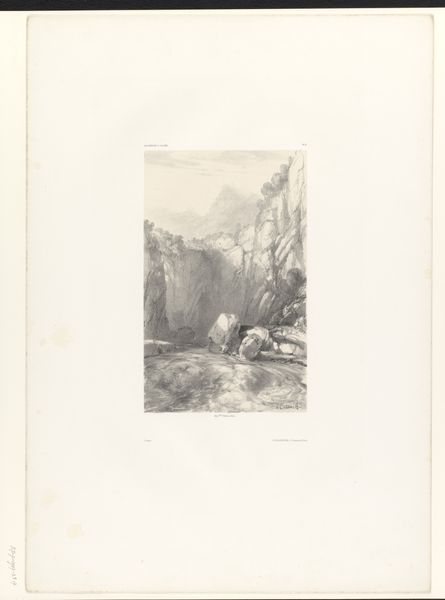

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

romanticism

#

orientalism

#

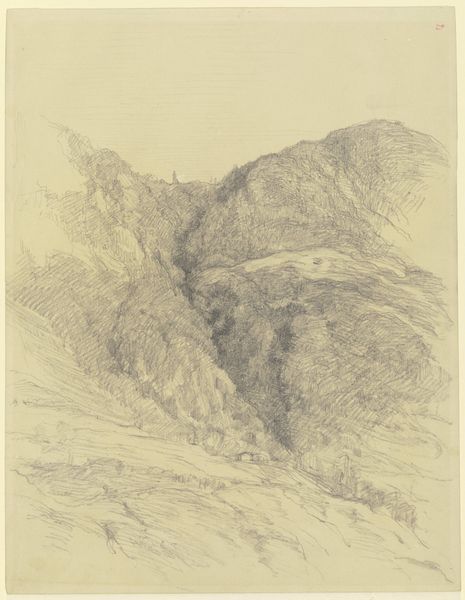

charcoal

Dimensions: height 586 mm, width 417 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Eugène Flandin's charcoal drawing, "Ravijn van de berg Kuh-e Pir Zan in Iran," created sometime between 1843 and 1854. I'm immediately struck by the imposing scale of the mountains, and the lone figure on horseback seems so small in comparison. How do you interpret this work? Curator: The contrast in scale is key. Consider how mountains often represent steadfastness, eternity even. But within the visual language of Orientalism, there's often a subtext of the Western gaze encountering the 'exotic' East. Does the small figure become a symbol of Western dominance, 'conquering' the landscape through observation and artistic representation? Editor: That’s a compelling idea. I hadn't considered the power dynamic at play. So, the landscape isn't just a neutral subject, but a reflection of cultural attitudes? Curator: Precisely! Think about the choice of charcoal. It’s a medium that lends itself to dramatic contrasts, mirroring the perceived contrasts between West and East, civilized and untamed. The ravine itself can symbolize a divide, both literal and metaphorical. What cultural memory does it invoke? Editor: Now that you mention it, the ravine, or the ‘divide’ in the landscape, mirrors how the West perceives a ‘divide’ between their culture and Iranian culture. Thanks for showing how something seemingly neutral, like a landscape drawing, can carry such powerful cultural and psychological weight! Curator: My pleasure! Seeing these familiar Orientalist tropes allows us to look at it more critically and appreciate the symbols Flandin worked with. We can, as a result, understand this image as a rich expression of a particular moment in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.